Think Like A Tester And Use Simple Questions To Test Requirements

Testing from requirements is a great way to get ahead of a problem. We can only test something that exists, and at the requirements stage the thing only thing we have that exist are our ideas. If we can find defects in the ideas, we can fix them before the ideas become product code. The hard part is finding flaws in something that we cannot watch run. We have to imagine issues and problems that are suggested or implied or inevitable from the requirements.

In this article I describe a requirements testing exercise I engaged in with a project of my own. I use a few techniques that were effective and relatively easy ways to expose problems not immediately visible in the first iteration of the requirements. Those techniques are:

- walk through any steps described in the requirements

- ask for clarification

- ask “what would happen if this step failed?”

- ask “what is the user supposed to do at this point?”

- ask if new issues indicate new requirements

Let’s look at the example.

System Under Test: A duplicate issue reporting detection application

I have a project I call DupIQ that detects duplicate issue reports coming from automation, bugs, or customer feedback. It gets embeddings for the incoming report, and then searches a vector database for prior issues. If any issues are above a certain similarity threshold, the incoming report is marked as a duplicate of that issue, and the report is written to an issue database. If no prior issues are above the similarity threshold, a new issue is created, the embeddings are stored in the vector database, and the new issue and report are stored in the issue database.

Simple Requirements from a Model and BDD:

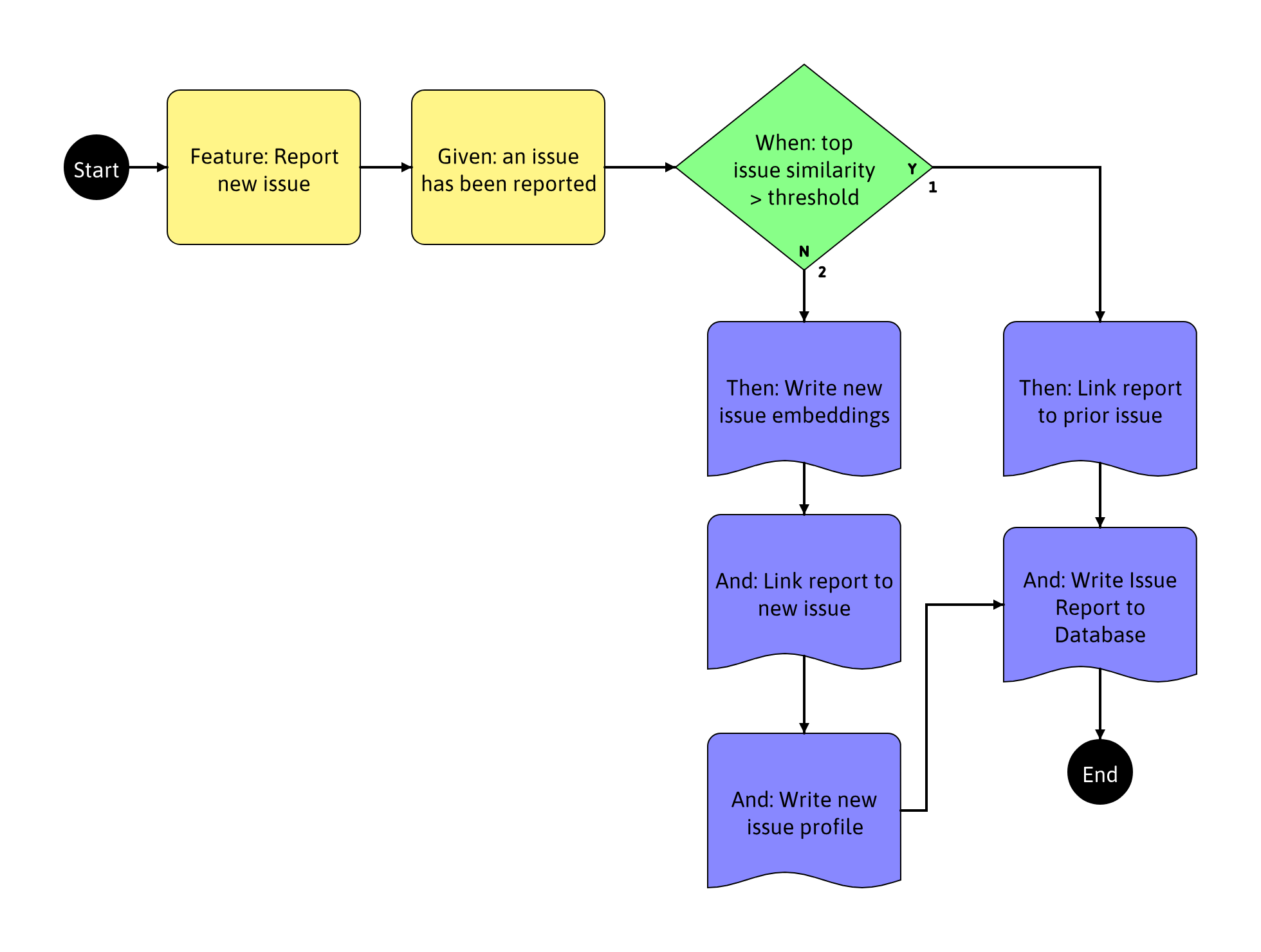

I created a model using TestCompass to describe requirements for the “Report Issue” feature.

Instructing TestCompass to create a 100% path traversal of the model, we can then export the cases as a Gherkin formatted description of the requirements:

``` Scenario: Report Issue - TC1 Given: an issue has been reported When: top issue similarity > threshold (YES) Then: Link report to prior issue And: Write Issue Report to Database

Scenario: Report Issue - TC2 Given: an issue has been reported When: top issue similarity > threshold (NO) Then: Write new issue embeddings And: Link report to new issue And: Write new issue profile And: Write Issue Report to Database```

From this, I was able to start my testing.

Requirements can come in almost any form. They may be diagrams, lists, formal expressions like Gherkin entries in a ticketing system like Jira, or large specification documents. You can work with almost any format.

Asking Simple questions to review the requirements

A large set of requirements can be daunting. They are usually long (unlike the short example in this document, but I will get to that). There are usually complex but maybe unstated relationships between features and behaviors. There is also something about reading “The application will flip the pancake in the air…” that numbs the mind into blind acceptance, suppressing questions like “What if the pancake wasn’t there? What if the pancake wasn’t solidly cooked yet? What if there wasn’t enough clearance to do the flipping?”

One way to simplify it is to ask simple questions. There are many questions one could ask. For this exercise, I used a short list:

Clarifying questions:

- How does this happen? This is useful when an action seems to happen as if by magic. The requirements specify something that is supposed to happen, but do not indicate the steps that made it possible. This is a bug in the requirements themselves, and the clarification will prove useful in further analysis.

- Where does this go? Many bugs in a system fall out of storage or sending data somewhere. Steps after and between storage points are often fragile, and usually drive requirements changes to fix bugs in the design.

Exploratory questions:

- What happens if failured occured here/now? Bugs and new requirements tend to become more apparent if we ask what happens when a given step, action, or requirement fails. Dependent actions, steps and requirements often fail even worse, and we usually find we need some kind of new recovery requirement, or perhaps a different way to meet that requirement which avoids failing in that way.

- What is the user supposed to do when this happens? This question is very effective with failure modes, because very often the user has to take some kind of action, or at least needs to know something. Maybe there is nothing the user can do, and we need them to know that. Maybe somebody else, such as an operator or support person, is the only one who can address the problem. Even for non-errors, sometimes the end result of an action needs to guide the user in a good direction.

Come up with a set of easy to remember questions you will ask as you go through the requirements. You do not need to be rigid, you can and should ask other questions. The tool serves as a memory device.

Structure helps

In my example, the requires are expressed both as a visual model and as Gherkin formated examples. Both of those create a structure that makes it easier to look at parts of the requirements one at a time, like steps.

Sometimes requirements are not written in step-wise format. Sometimes they are lists, sometimes as short user stories. Sometimes they are less structured. The “ask a simple question” technique still works in any format, although you might find yourself having to work harder to see the relationship between parts and pieces the more unstructured the format.

If you are having trouble reviewing the requirements, feel free to create a structure of your own. Choose any structure or format that helps you think. Share with others on the team, they often find that kind of thing helpful.

Raising Issues

In my exercise, I came up with the following bugs after the questions above for the requirements on “Report Issue.”

- Need clarification on how issue similar is established

- Where are embeddings stored?

- Where are the issue report and issue profile stored?

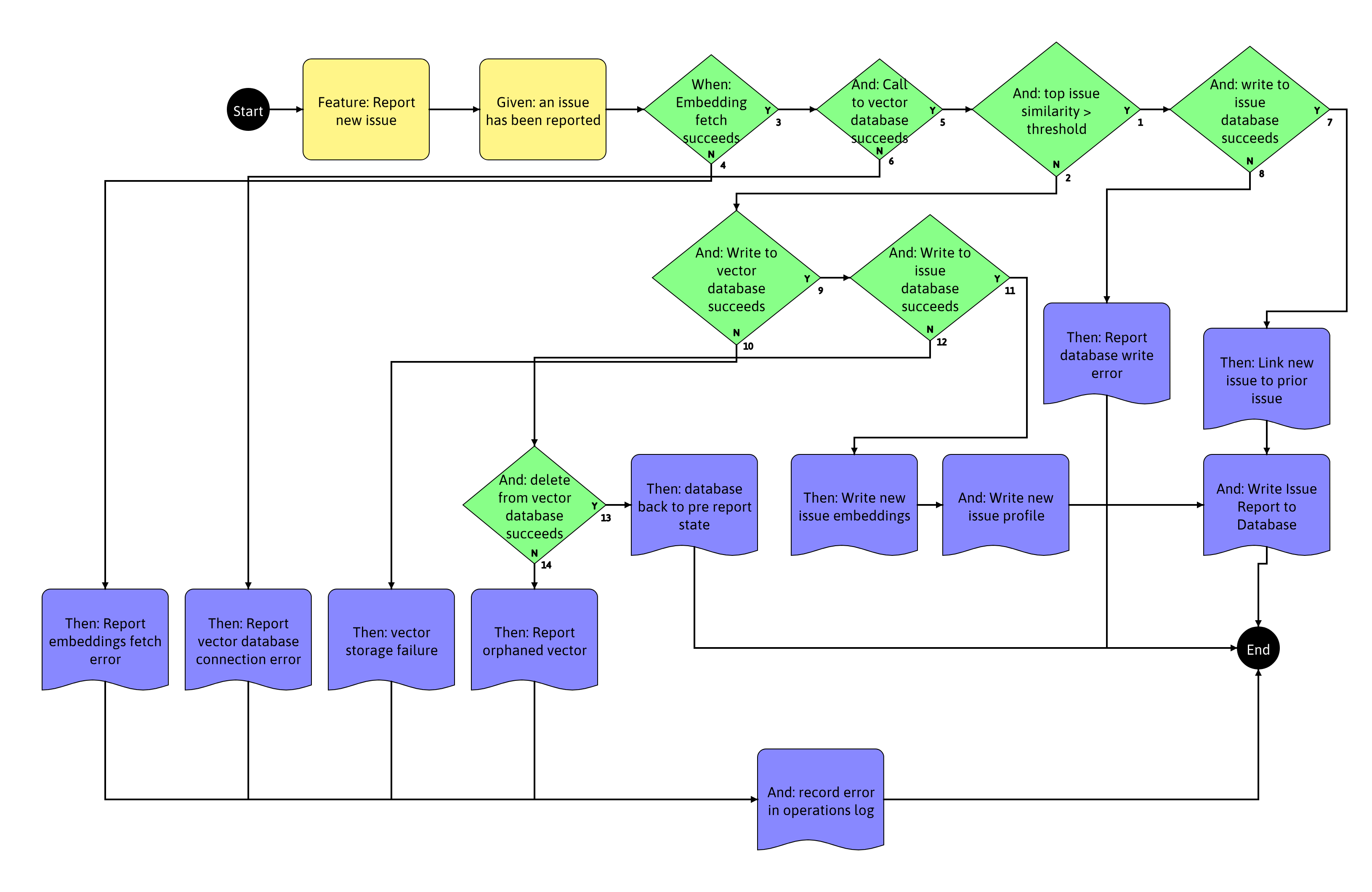

This drove an update on the model. Issue similar is established by retrieving embeddings for the reported issue, and then performing a search against a vector database to get consine distance from prior issues to establish similarity. In the case of creating a new issue, the embeddings for the reported issue would be stored to the vector database, and then the issue report and issue profile would be stored to the issue database. Two whole components of the system were missing in the prior requirement. Review of the new requirements yielded the following new questions:

- What if retrieval of the embeddings fails?

- What if writing the embeddings fails?

- What if writing the issue report and/or the issue profile fails?

- It seems that if embeddings write succeeds and issue profile write fails, there is an orphaned embedding in the vector database, does that suggest a new requirement to clean up orphans?

- What is the end user supposed to do for each of the failures on embedding fetch, embeddings write, issue report and profile write, and likewise on orphan failure?

- Is there a missing feature for operations notification of any of these failure states?

That set of questions prompted a redesign of the requirements to account for each of the failure states and how to respond to them.

An expansion of the test cases, and export to Gherkin describes the new four times expansion in number of cases (at the bottom of the article).

Testing by requirements is iterative in nature. Questions asked motivate changes to the requirements that usually raise new questions. Requirements will tend to grow substantially in one or two iterations.

The required ending

My intent of this article was to demonstrate an effective and easy way of testing an application from requirements. This example was small. Most projects will have a much larger, richer set of requirements. That does not change the effectiveness of the technique. You can get a lot out of asking for clarification, finding a simple question such as “what happens if this step fails?”, or “what is the user supposed to do next?”, and then applying enough structure to the requirements that it makes asking the question easier.

Appendix: That big pile of Gherkin

The Gherkin below was unwieldy and cumbersome, so I moved it from where I discussed it above to the end of the article.

Scenario: Report Issue Error Handling - TC1 Given: an issue has been reported When: Embedding fetch succeeds (YES) And: Call to vector database succeeds (YES) And: top issue similarity > threshold (YES) And: write to issue database succeeds (YES) Then: Link new issue to prior issue And: Write Issue Report to Database Scenario: Report Issue Error Handling - TC2 Given: an issue has been reported When: Embedding fetch succeeds (YES) And: Call to vector database succeeds (YES) And: top issue similarity > threshold (YES) And: write to issue database succeeds (NO) Then: Report database write error Scenario: Report Issue Error Handling - TC3 Given: an issue has been reported When: Embedding fetch succeeds (YES) And: Call to vector database succeeds (YES) And: top issue similarity > threshold (NO) And: Write to vector database succeeds (YES) And: Write to issue database succeeds (YES) Then: Write new issue embeddings And: Write new issue profile And: Write Issue Report to Database Scenario: Report Issue Error Handling - TC4 Given: an issue has been reported When: Embedding fetch succeeds (YES) And: Call to vector database succeeds (YES) And: top issue similarity > threshold (NO) And: Write to vector database succeeds (YES) And: Write to issue database succeeds (NO) And: delete from vector database succeeds (YES) Then: database back to pre report state Scenario: Report Issue Error Handling - TC5 Given: an issue has been reported When: Embedding fetch succeeds (YES) And: Call to vector database succeeds (YES) And: top issue similarity > threshold (NO) And: Write to vector database succeeds (YES) And: Write to issue database succeeds (NO) And: delete from vector database succeeds (NO) Then: Report orphaned vector And: record error in operations log Scenario: Report Issue Error Handling - TC6 Given: an issue has been reported When: Embedding fetch succeeds (YES) And: Call to vector database succeeds (YES) And: top issue similarity > threshold (NO) And: Write to vector database succeeds (NO) Then: vector storage failure And: record error in operations log Scenario: Report Issue Error Handling - TC7 Given: an issue has been reported When: Embedding fetch succeeds (YES) And: Call to vector database succeeds (NO) Then: Report vector database connection error And: record error in operations log Scenario: Report Issue Error Handling - TC8 Given: an issue has been reported When: Embedding fetch succeeds (NO) Then: Report embeddings fetch error And: record error in operations log