Why_is Rerun A Valid Test Strategy For Cicd

Did I break something?

In a CI/CD environment, the main question on a developer’s mind is “did I break something that was working before?”

That is a different question than “is something broken?”

It is also a different question than “does the product work” or “does the product meet requirements?”

All of these are valid questions, but when we are at the point of continuous integration and continuous deployment, whether something is broken, or whether the product works correctly and meets all requirements is far too large a question to ask and answer in the time allotted.

But we can feasibly ask if the developer’s change broke something that was working before. We do this by defining “working before” as the set of tests we run during the CI/CD pipeline. If they were consistently passing before, and if they consistently fail now, then the developer’s change broke something.

Easy-peasy.

But what about when they are not consistently failing? Can we say for certain the developer’s change broke something? We cannot. Without a deep investigation the answer is a matter of probability. What we need is some understanding of that probability. That is why we re-run the tests.

But what does it mean when we see a failure only once out of two tries?

To answer that, we need to ask another question.

If there was a flaky failure introduced into the code by the developer’s change, what is the probability you would see that failure the very first time the change was tested?

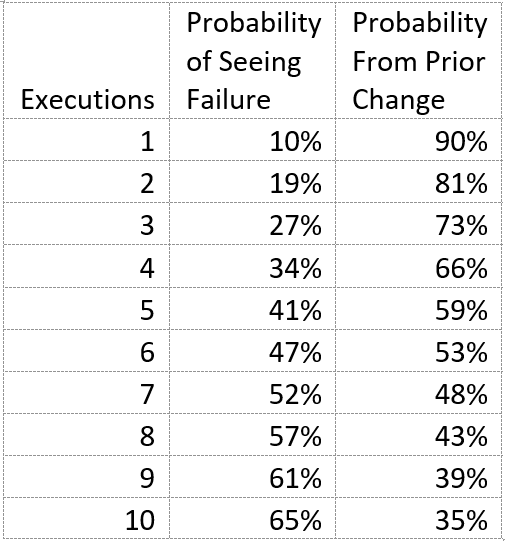

Imagine a failure that occurs 1 out of every 10 attempts. The probability of seeing that failure on the first test is only 10%. If we consider this in reverse, there is a 100%-10% = 90% probability that the failure was introduced by a previous change. If imagine multiple executions of the same test, we can ask what is the probability of seeing the failure after several executions? We can find the raising the base probability of not seeing the failure on any one run by the number of runs and subtracting that from 100%. This gives us the following table of probabilities:

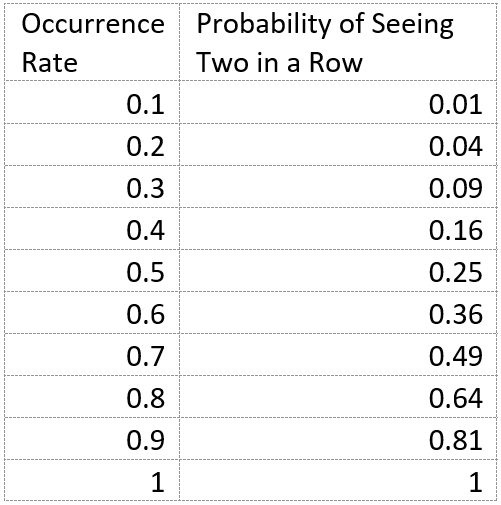

Now consider the probability of seeing a failure with a 10% probability rate occur two times in a row. That is 0.1 * 0.1, which is 0.01. The likelihood of a 10% failure occurring two times in a row is only 1%.

Let’s see how this works for other failure rates.

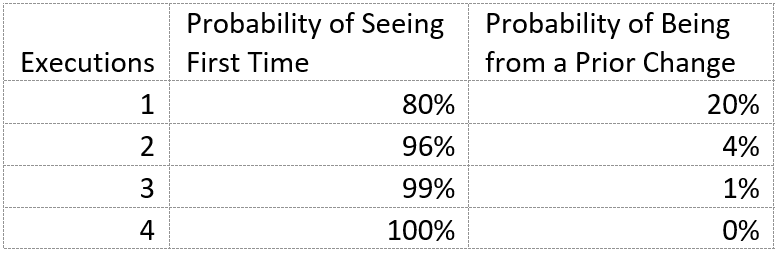

By the time we are at a coinflip, we are at 80% occurrence rate. Let’s look at the likelihood of seeing 80% occurrence rate after various number of executions:

The statistics are clear. If a failure occurs two times in a row, then we are looking at a very high probability the change introduced the failure. If not, we are very close to whatever change it was that introduced it. Even if we are sometimes mistaken about that, the rate at which we make that mistake is kept to a minimum.

The truth about flaky failures is that by the time you see the failure, whatever defect caused it has almost always already been released. It is very infrequent that the change under test is the source of the flaky failure. When you consider what it takes for a flaky failure to appear immediately, it demands a high rate of occurrence which doesn’t pan out against the experience most people describe.

This is why re-run is a good strategy for CI/CD. Not because flaky failures should be ignored, or that they represent uninteresting failures in the product. Re-runs are a good strategy for CI/CD pipeline check failures because they give us the information we need to know to make a probability bet about whether or not the current changes broke something. Failing twice establishes a high probability the failure came from the change. Not failing twice, very low probability.

Is something broken?

Now we come to the point of anxiety about re-runs. Is something broken?

Yes.

Whether the flaky failure is coming from the product, the test code, the environment, or something else, the failure is an indication something is broken. But it probably wasn’t the change just submitted that caused the break. Re-running the test does not change the nature of the failure. It gives us information about the failure we can use during investigation.

The mistake is to throw away the information after the re-run. Record the failure somewhere. Investigate. There is something that probably needs to be fixed. I am not going to spend time in this article going into the details on that, because the main point was to get into the statistical matters above about why re-run works as a strategy. But it is important to remember that it works ONLY because we are asking and answering a very specific question, “Did I break something?” So long as we remember that is the reason for the re-run, we realize there are other questions to answer, and we get on with those.