Testing To Support Experiments

Is this what we wanted to measure?

In a recent post, I introduced the idea of supporting “Is this the right product” questions with testing. I did not have a really good example when I wrote the article, so I made one up. Since then, I came across one in Bing, so I am writing this article as a follow-up.

What follows is just my opinion, and that only counts if you count it

A friend recently asked me about testing large language models. I am not an expert, but I am vaguely familiar with how they are tested. I used Bing search to find information to support my answer.

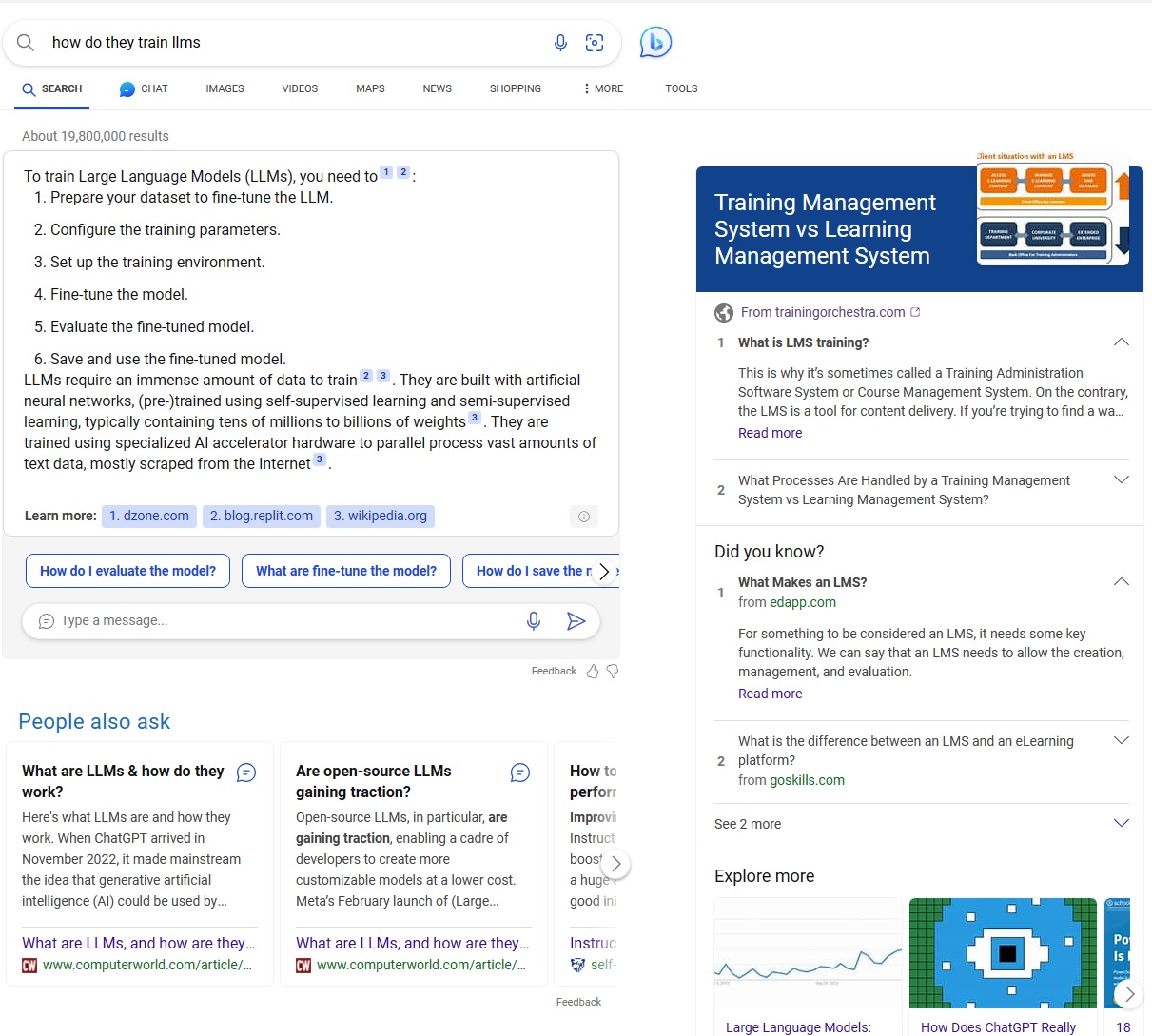

I typed “How do they train llms” into the Bing Search box.

Bing returned a set of results with a mix of real page hits and answers created by generative AI. Bing placed the generated content at the top of the results. In this particular instance, I wanted human generated content, so I scanned the results for something that seemed to come from an actual website instead of AI. As shown in the page below, there is a section marked “People also ask”, and below that a block of text titled “What are LLMs & how do they work?” Below that block is a link to a website. As far as I could tell, clicking this block would take me to that website. I clicked.

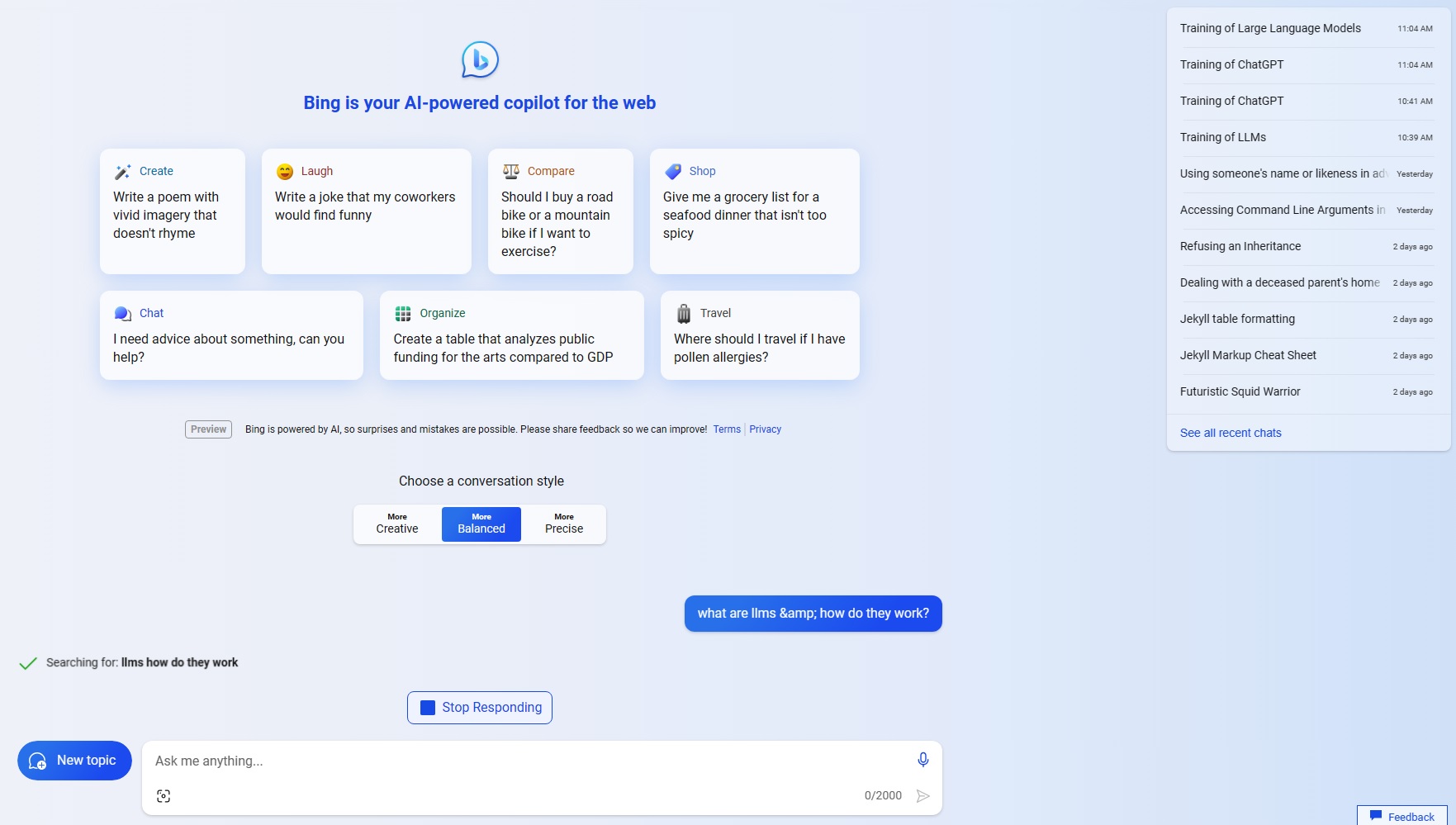

Bing did not take me to the website I wanted. It didn’t even take me to a page about training LLMs. It didn’t even take me to a block of generated AI content about training LLMs. What it took me to was a commercial for Bing’s generative AI feature.

I did not like this behavior. It did not give me what I wanted. I wanted an article about training large language models, and instead I got a commercial. I felt like Ralphie in the movie “A Christmas Story” when the radio message he decodes from his brand new Little Orphan Annie Secret Decoder ring is “Be Sure to Drink Your Ovaltine.”

I dismissed the page and tried more searching.

Whether or not this behavior is good, desirable, is an answer in aggregate. Me liking it or disliking it only counts when dumped in a pile of other people’s opinions. Those opinions are assessed by the next thing they do. Somewhere back at Bing, someone has a set of “next thing the user did…” measurements, and those are used to decide whether or not the feature behavior is good or bad. If it drives something the Bing team wants to happen, it is good. If it drives something the Bing team doesn’t want to happen, it is bad. Our beavhiors are constantly being measured.

But what if we aren’t measuring what we think we are?

What are we measuring?

When I was collecting the screen images for this article, I found Bing did not always give me the same results. Sometimes it gave me the first page with generated content at the top, and sometimes it gave me a page with no generated content at all (pre-AI Bing looking results). Very likely the different results are part of an experiment. Let’s keep that in mind. The Bing team (like everybody else) is running an experiment to see which product changes cause the end user to do things the product teams considers good, positive.

If you remember in the results above, the text I clicked was an AI summary with a link to a real website below it. Let’s called that a “Generated AI Sunmmary Result” for sake of reference.

We cannot know for sure, but we can pretend that the experiment is testing a hypothesis like this:

Generated AI Summary Results which take the user to a how-to-use conversational AI page will drive user engagement with Bing’s conversational AI bot.

If that is the hypoothesis, then I would say the measurement the product team got from what I did next was probably in line with their goals. I hit BACK and scanned the prior page for different links. They got a solid “FALSE” measurement from me. All they need to do is count up what everyone else did and they can draw a conclusion.

What if that isn’t the hypothesis they are trying to test? What if the behavior in Bing is a bug, from their perspective, and I was taken to a page that did something other than what they thought it did? What if clicking the link was meant to take one to the actual website, or perhaps a page of more in-depth generated content based on that website? Imagine any of these hypotheses:

- Generated AI Summary Results which take the user to more in-depth generated AI content will drive user engagement time on the page up.

- Generated AI Summary Results which take the user to the page summarized will drive user satisfaction measures with search results up.

If the product team takes my “BACK” response as a negative engagement vote on the feature, but the product wasn’t even exhibiting the behavior they wanted a measurement for, then the time spent on the experiment was a loss. If the behavior is an every single time event, deterministic, then it is likely this mistake will be caught if someone analyzes the results closely enough. But if the behavior is intermittent, happening only on some clicks and not others, then the effect might confuse the analysts. They may be seeing an error rate in their measurement large enough to tip away from a more correct measure of the intended change.

When we are planning an experiment, we should test for the following things:

- Do the behaviors we are testing work as intended for both the control and independent variables?

- Do we have sufficient measurements and data in place to measure the effect needed for the experiment?

- Do we have sufficient measurements and data in place to tell if the product is not doing what we want? Will be able to isolate for errors in the sample?

- Do we see or have we discovered any risks to the experiment?

- Do we see or have we discovered any risks to existing product behaviors?

Getting ideas for your testing

Whether you are preparing changes for your next experiment, or working on a big product release, it always helps to know how to organize your thoughts and ideas. I present a simple way of doing that in my book, “Writing Test Plans Made Easy.” I guess that makes this another crummy commercial, but perhaps a useful one?