Find Your Tester Mindset Via The Formatfont Dialog

The tester mindset and the FormatFont dialog

This article is part of a series where I explore the tester mindset

via interview questions I found effective for

finding people who demonstrated application of

a tester mindset.

This article is part of a series where I explore the tester mindset

via interview questions I found effective for

finding people who demonstrated application of

a tester mindset.

I have found different questions tend to demonstrate different kinds of testing behaviors. This question involves recognizing tricky problems inside deceptively simple feature sets, examining a very user oriented UI, going beyond rote enumeration of an applications surface behaviors, and having an approach to cut down a rapidly unmanageable problem domain.

All that from FormatFont? Yup.

Bring up the app, give them the chair, and ask the question

If I can, I really want to see the tester working directly with the product during this question. I want to watch how they interact, explore, what steps they take to discover behaviors, elminate variables, introduce new ones, how they build a model of expectations. My script goes as follows:

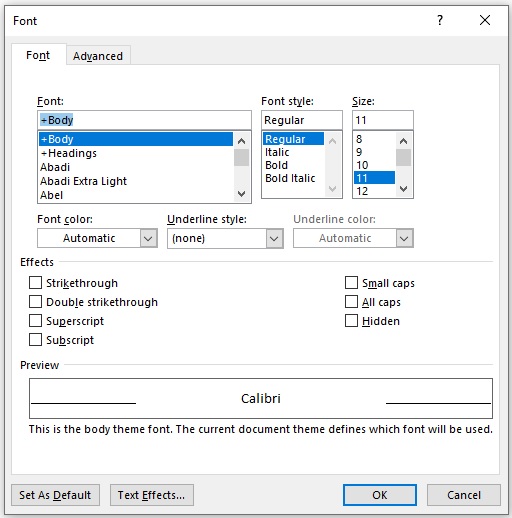

Setting: My computer has every application but Microsoft Word closed. Word is open with the Format Font dialog displayed.

Step out of chair and pull it back.

“Here, take my chair, sit at my desk.”

Wait for them to take a seat. Step aside to where I can observe and be sure to give them lots of room to feel comfortable.

“On the screen is Microsoft Word with the Format Font dialog open. Are you familiar with this feature and what it does?”

If they say yes, I proceed. If they say no, I give a brief explanation of what the dialog is for.

“Let’s pretend you are a tester assigned to test the Format Font dialog in Word. How would you go about testing it?”

At this point I let them do whatever they intend to do. I answer questions if they offer them, but only clarifying questions. If they ask me something such as “What would a good test be?” or “Is this a good testing idea?” I always throw it back at them with something like, “That is what I am asking you.”

Green Flags

The good news is the green flags are really green. Just one or two are a strong hint that a candidate has potential to be a good tester. They usually respond well to formal test training after hire. The bad news is that some people never demonstrate any of these green flags (or others not listed here), even when they demonstrate other strong technical skills, like coding.

Summary and synthesis

This is not a direct testing skill, but it is a habit a lot of strong testers deploy very well. Not all good testers synthesize well, so absence of this flag is only a problem if the negatives are pulling strongly on the candidate.

Candidates good at summary and synthesis tend to group and categories product behaviors, risks, testing problems. They may or may not know the categories, and if not they tend to intuit them. They then attach meaning and strategy and approach to that synthesis. This allows faster analysis, easier description of problems, and easier creation of models of how the system works.

An example of the behavior might look like this:

“Well, we have each of the file attributes to consider, so font name, style size and such. That keeps on going with everything you see here.”

contemplates the list

“We probably want to get each of these settings, but I am starting to wonder how they work in combination with each other. Some of these features might have problems if used together…”

An aptitude for cluster and grouping ideas tends to build ideas on top of each other. In the example above, we get a rapid acknowledgement that the strategy will focus on each of the controls and the values in them - we don’t need to hear the full list to understand that much. The the candidate starts using those groups to consider other problems - such as mixing features together in combination. That basic idea, mix the clusters, is a form of idea creation that promotes exploration of further test thought.

Interacts with the product

Strong candidates will always touch or use the product controls. Assuming they can (physical abilities vary) they go hands on mouse, fingers on keys. They may interact with other controls such as voice, braille controls, special controls. It doesn’t matter, the point is a strong testing candidate will get into the product so long as it is there for them to do so.

Strong candidates like to check their assumptions by interacting with the product. Does it do what they thought it would? A lot of candidates are surprised by product behavior, and for strong candidates that surprise does not throw them, but instead excites them. It suggests there is far more to explore than they thought. When the app does something other than they assumed it was, they want to know, was that a bug?

Recognizes differences

Strong testing candidates tend to notice differences that other candidates gloss over. For example, the font typefaces listed in the “Font” control. Are they all the same, or are there important differences?

Strong candidates demonstrate this behavior even when they know nothing about a given technology. They seem to generally realize that lists of things often have difference within the list that behave differently. Just bringing up this idea as sideways mention, maybe phrased like the following or similar is a promising sign:

“I am not so sure how all of this works, but I am wondering if some of these different fonts might work differently then others. Like, what happens if I pick and choose some of them, are the other controls affected?”

There are in fact numerous differences in fonts, a non-exhaustive list would include:

- some are built into the printer with no on computer equivalent

- some fonts are limited in terms of font style capabilites, so selecting them might change whether or not “italic” or “bold” or other features are available

- some fonts come in preset size ranges, which will affect the size box

- some fonts support certain effects that others do not

- some fonts are capable of advanced features such as ligatures

Mixing and matching

Testers tend to mix and match features together. Some of them are good at ferreting out combinations that might not work out so well together.

The Format Font dialog box has a good set of combinations in its “Effects” group. The UI presents them as a series of checkboxes which seem to work together indiscriminately. A closer inspection suggests otherwise. What does it mean to turn on both “Strikethrough” and “Double strikethrough”? How about both “Superscript” and “Subscript.” Those seem mutually exclusive. It seems interesting to explore product behavior trying to set them both on at the same time.

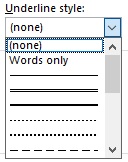

How about other mixes and matches? Consider the “Underline Style” box.

So many types of underlines to choose from, which opens another interesting question (How does the app make so many? Are those built in to the font technology, or does the app draw them… how to find out?), but consider how they might combine with some of the other font features. How well do the underlines align when mixing font size on a line? Typeface? What about superscript and subscript? What if you turn on any of those underlines AND strike through or double strike through? A strong tester will be curious.

And it turns out that curiosity might pay off. The real answer (back in pre-2000 when I had to deal with this a lot, so there might be new features which change some of this) is that some of the capabilities are built into the printer, some into the font technology, and some the application has to do entirely on its own. “App does it on its own” tends to be the most fragile, especially when dealing with integration and combinations, but you can also run into problems with external technology takes over and the app tries to mix that with behavior it implements on its own.

The trick here is not to check if the candidate knows this information. What you want to see is them asking the types of questions and engaging in the type of exploration which leads toward these kinds of discoveries. Mixing and matching is one of those behaviors.

Smelling “tricky stuff”

There used to be a set of special effects features in the Format Font dialog that seem to have gone away (perhaps they are in there somehow and my current settings suppress them?). They included things like blinking, marquees around the letters, and other animations. None of this came from the OS, none of this was built into any of the font technology. Word used to do them all by itself.

Stuff done by the app on its own with system level resources tends to be buggier than stuff the system does for the app.

Testers seem to have a gut instinct for things that seem hard or tricky. They have a sense of something that is different than usual behavior. They wonder “How did they do that?” If I had a tester that navigated onto the Advanced tab and had a visceral reaction to the special effects, I add a few points in the “hire” direction.

Searching for oracles

One of the key problems in testing is knowing what one ought to expect. If you type something in a box, and the screen flashes red while the computer emits a loud “beep!”, was that what it was supposed to do?

During this session, the tester is neither presented with a specification or a design document. I will answer some questions, but I prefer to let them try to figure out the answer. In particular, I want to know what they will do to figure out what they ought to expect. Some examples:

- use various logical means of excluding possiblities

- check behavior around different ranges

- look at similar apps (WordPad is right there…) with similar features

- start thinking about and describing things from a user’s perspective, e.g. “let’s say I wanted to enter the font name, but I got the name wrong… then what? Should it do this in that case, or would it be easier if…?”

- dare I say look online… there is a world of information out there, and it is probably what they would really do on the job anyway

Exploiting clever ideas for shortcuts or complexity

This is a behavior a lot of interviewers try to force by asking a generic testing question that works really well in this example.

“Let’s pretend you are allowed to execute only one test for this feature. It is still critical to cover as much as you can and get the highest priority bugs fixed. What would that test be?”

This is a highly contrived, and rather stupid constraint. But it forces the candidate to consider optimizations and priority and risk and strategy all in one go. There is no right answer. Priorities are not always the same, and some testing problems create exclusive conditions - e.g. invalid data entry that the app ought to abort or return an error for frequently cannot happen at the same time as covering complex, but valid data. This question forces the candidate to consider these possibilities.

A strong candidate tends to embrace such a question aggressively. They look for combined coverage. They look for certain kinds of tests which, as the layers of fixing the bugs are addressed tend to peel back the onion of getting at more and more problems. They talk openly about the dilemma of covering high priority use cases (which might already be addressed elsewhere) versus covering lower priority but much more likely to break conditions and whether covering the latter demonstrates lower risk on the former or not. They will openly weigh, and maybe even agonize over, decisions about priority. They will wallow in the ambiguity rather than shy away from it.

This just one class of clever ideas, and is an interviewer technique to force some to the surface.

Red Flags

There are some red flags that worry me the candidate may not be suited for testing. Something about these red flags is they tend to appear exclusive of green flags. It is not common that a candidate will offer one of these ideas and also demonstrate a number of the behaviors that indicate strong testing potential. If that were to happen, it is my inclination to emphasize the green flags over the red.

The candidate ever says “That’s all.”

There is something about strong testers that keeps them from running out of ideas, and even when they do run out of ideas they tend to get very bothered about it. The very notion that one might run out of testing to do seems to agitate and irritate an effective tester. Even when they have never been exposed to testing concepts, there is a feeling in their gut that something more remains.

By contrast, some people shut off idea generation quickly and confidently. They will assert, even after multiple prompts (personal bias, if I have to prompt you even once with “Are you sure that’s all?” you have a very deep hole to dig yourself out of) that there is no more. This might shock some that I find a lot of developers fit this bill nicely. I have seen plenty of individuals do a whiz bang job at writing up all sorts of complicated algorithms and rip open all sorts of puzzles, only to respond with a near empty list of possible ways to challenge the behavior of whatever code they are handed.

Rote feature enumeration

The behavior goes like this

Candidate looks at screen and starts reading from top left of the dialog, moving right and down.

“I would test the font name. I would do each of them, Abadi, Abadi Extra Light, Abel…, then the font style, so Regular, Italic, Bold, Bold Italic. Then the font size…”

And from there they keep going. One control at a time, naming every option. I try to catch this behavior as quick as I can. Enumeration and recognition of the features is important, so I don’t want to shut them down too early. I also want to give them the chance to decide on their own that they are using up valuable time and probably ought to figure out ways to shortcut what they are saying.

But most of all, I want them to see past the stuff on the surface. After I give them a chance to correct themselves, if they do not, I start dropping hints as questions, such as:

- Of the items in that font size list, which would you choose and why?

- Do you think covering every font name in that list is important? Is there anything else you would try, seeing that feature beyond just covering every name in the list?

I find that rote enumeration predicts very poorly for getting back to green flag behaviors. Once I see the behavior, I nudge as much as I can because continued demonstration of the same rote enumeration gives me no more information about the candidate skills. I respect their time to much to let them lose a chance to demonstrate something positive.

Never using the product

I put them in my chair with the application loaded and ready for a reason. I don’t just want to hear them talk. I want to watch them work. When they encounter the font size control, do they ever click on it? Do they scroll the list? There is an edit control at the top of that list. Do they ever type anything inside of it? If they do, have they considered typing a value that is not in the list? Have they considered typing a value that seems odd or ridiculous, like “pi” or “-23” or “1.0000000000000000000000009”?

Testing is about discovering truth through observation. It is an empirical craft, and observation demands activity. You have to create a condition, observe it, think about it, and describe it. Your ideas and hypotheses are going to constantly fall apart and you need to adapt. If a person, when presented with an application to test, never once even interacts with it, that is a major red flag to me.

Blindly accepts surprising product behavior

The opposite of some of the green flags above, some candidates will respond to surprising or unexpected behavior with a simple “Oh,” and never dig any further. They just accept what they observed, do not question whether it is good or bad. The don’t even question if there mistake in what they believe they saw.

I don’t want to lean on this red flag too heavily. Not everything is going to stand out to all of us. It is also very behavioral, and it is easy to mistake a low-energy response for lack of curiosity. There may be a lot going on in the person’s mind. Or they might be tired. It is worth probing this with a question, such as “What do you think of that behavior? It sounds as if you expected something different?” to see if maybe they really are thinking of something. This might be a green flag that is suppressed, and checking on this might trigger the candidate to “wake up” and turn the interview around.

Developing your tester brain

The recommendation I would offer anyone that wants to, or maybe needs to, grow some tester mindset muscle would be to consider some of the green flag behaviors and exercise them on an existing application UI.

- Summarize and Synthesize: this shortens the number of items you have to think about and focuses on shared attributes that usually have shared test implications.

- Interact with the product: few things trigger the testing imagination as well as using the product to do something. Get in and use it, and as you do make notes (physical or mental) of other things you want to do. Treat this time as if you don’t have something else to get back to, this is what you are doing.

- Look for differences: are all the times in a set of choices, or in a list box, or using controls that look the same really the same? Are the inputs or states different in important ways? As a developer you probably have better insights about that than anybody else. Exploit them, because the bugs live there.

- Mix and match: A lot of testing is about combinations of state and input and behavior. Start with synthesis to make large groups easier to talk about as clusters, and then start combining the groups. So will make no sense, others will be very interesting.

- Smelling tricky stuff: This may be something that you as the developer know better than others. If you spent more time making something work than everything else inside a given UI, that is probably something worth testing. If everything else came “for free” from the operating system or some set of libraries, but for this one thing you had to write the behavior yourself, focus there.

- Search for oracles: Look for ways to help you know if behavior is right or wrong. Whatever guide you used as a developer will help a lot, but sometimes we can find oracles that work splendidly in a testing context that you may not have considered while writing the code.

- Look for shortcuts and complexity: This is about making your work easier, put more impact and effectiveness into less effort. Can you do the same thing as a lot of tests with fewer? Can you drive up complex behavior with simple changes to the test approach?

Also consider the red flags, and how you can use an inclination toward them as a sign to take an alternate approach.

- Do not accept ‘That is all’: Saying ‘that is all’ for test ideas to oneself is kind of like saying ‘Yup, the Earth is flat.’ If you drew that conclusion you should immediately know something is wrong in your reasoning. It may also be an indication similar oversimplification was in effect during design. Try toward ideas that produce expansion such as combinations, looking for differences in the set, fast ways to create complexity.

- Switch away from rote enumeration: When your thinking is taken over by listing everything you see in front of you that is a sign you are not engaging the testing aspect of the problem, the part that looks for problems. It also might be a sign that the feature set is long, and tedious, and might some issues overlooked in design and development. Step back and switch to synthesis.

- Force yourself to use the product: Not using the product while thinking of test ideas is a demonstration of a block in your mind preventing you from engaging the test problem. Treat that as a warning sign that you are not digging deeper. The best way to get over this is to dedicate time to nothing else but using the product and taking notes.

- Stop yourself after a surprise: More so for a developer, if the product ever does something that surprises you, catch yourself before just passing by. Take notes of the behavior, write down or at least remember that it surprised you and compare it to what you did expect. Build specific testing and exploration around that surprise. It may not be a bug, but it for sure was an indication of a distance between your mental model and how the product really behaves. Closing that distance - that is real testing.