What To Do When The Test Results Are Wrong

Responding to the challenge properly matters

In this article, I use the phrase “the person testing” because

the principles here apply to anybody; a tester, a developer,

a product manager, a business owner, or the customer. There

is a productive way to deal with bug reports that do not

seem correct, and there are non-productive ways to avoid. It

does not matter who is doing the testing, the principles are

the same.

In this article, I use the phrase “the person testing” because

the principles here apply to anybody; a tester, a developer,

a product manager, a business owner, or the customer. There

is a productive way to deal with bug reports that do not

seem correct, and there are non-productive ways to avoid. It

does not matter who is doing the testing, the principles are

the same.

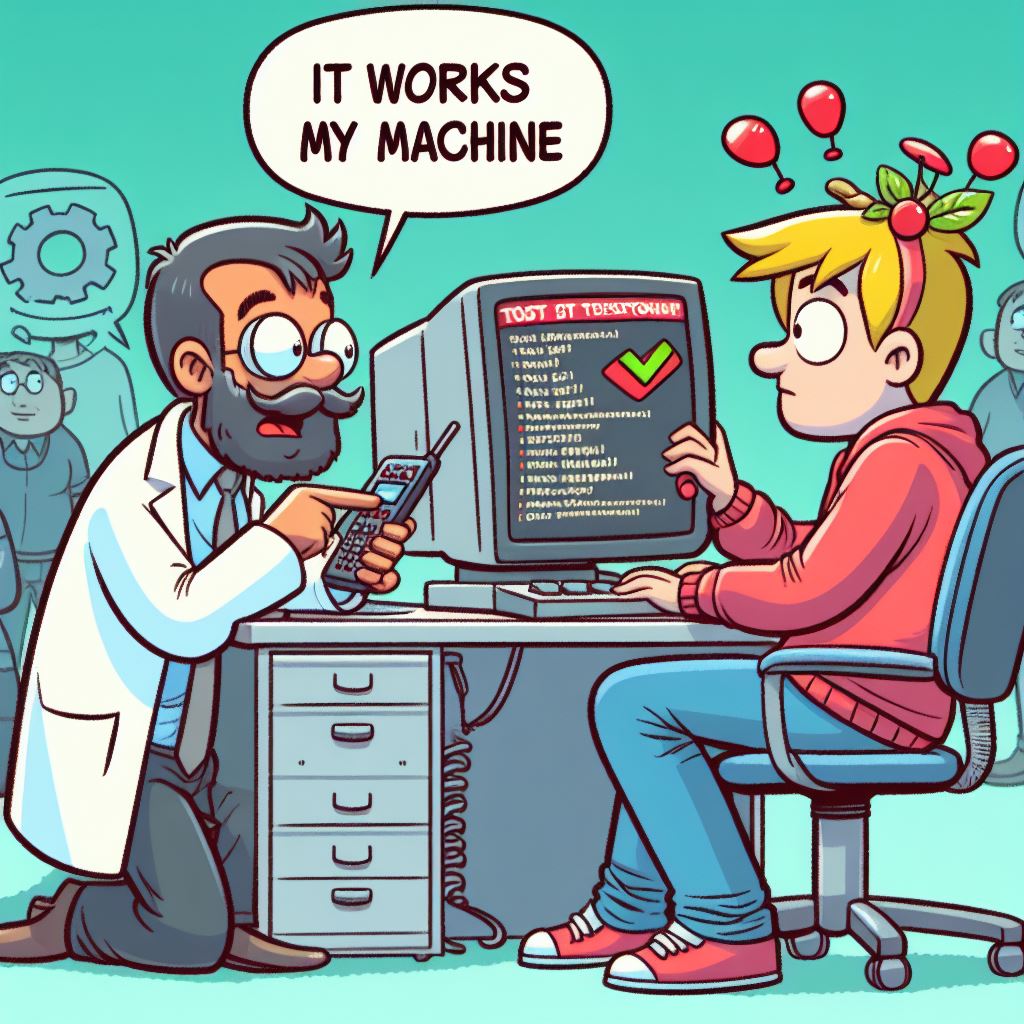

“It works on my machine” and other maladies of bug reporting

On a post submitted by a colleague of mine, someone posed this question:

Imagine that somebody wants to be a better tester. They submit a bug “expected result is OR, actual result is XOR”. In reality the system behaves as OR. What would be a proper next step?

They can go towards “yes it is OR, but the system is bad anyway” path or they can reflect on why there was a false positive and proceed with bug hunting as a more experienced tester.

What should we do, all of us, in this case? Not just the person testing, but everybody in the relationship?

Someone who isn’t the one who did the test and reported the result

- check if the reported results are repeatable, look for possible variations or factors like repetition which could explain a difference in reported result and what you see

- state what you observed, what you tried, and indicate that to whomever reported the results

- treat this as “just the facts” transaction, remove entirely any appearance of insults or hurt feelings or attacks on professionalism or challenges to a person’s integrity

Testing is about flow of information to make a decision. You want that flow unimpeded. There is too much testing work to do, too many risk possibilities to investigate to have barriers to that investigation, especially any that stem from a concern over punishment for being wrong or incorrect. A straightforward enumeration of the facts of the reported behavior versus actual product behavior is useful and helpful.

There is a real possibility that your own belief the test result is incorrect is wrong. It is not impossible for someone to report something that did not actually happen, but it is the minority case. More often whatever the person reported really did happen and the failure to reproduce it at another time comes from a misunderstanding of the real test conditions. Both parties are culpable in this misunderstanding. The bug report recipient is just as obligated to due diligence on investigation as whomever submitted the bug report. Their capacity or ability to investigate my differ, but they still have a role to play.

Someone who is testing

- check the reported steps again and see if you get a repro again

- check whatever evidence you have from the testing - logs, notes, screen grabs - is there evidence that can confirm your observation, or does it corroborate what the challenge asserts, that it did not happen?

- if you do not have direct evidence to support observations, consider how to improve your testing practices to include it - application logs, test notes, test script logs, screen captures - anything which you can check later against the bug report to see if it matches what the evidence states

- if the reported steps do not repro again, decide whether or not further investigation is merited. If the bug seems very bad, it is likely worth trying to get more predictable repro steps. If the bug seems not worth pursuing, maybe cut your losses

- no matter what you do - whether confirm your bug report or determine you were incorrect - provide an accurate and honest and professional answer describing your analysis

People who test have an obligation to deliver truth about product risk.

One of the most important parts about testing is to always challenge beliefs, assumptions, and assertions of fact. Testing is an activity where we make observations, where we find evidence that falsifies beliefs we want to or rely on to be true. If testing reverts to accepting factual assertions unchecked, with no skepticism or no challenge, then we are no longer testing, we are just engaging in an expensive and fancy game of taking dictation.

When someone says the bug reported is not true, the reported behavior does not happen, that is an assertion which should be challenged. The person testing is obligated to check that assertion both to check their prior testing results, but also to find if the assertion itself is wrong. There is almost always a more important problem discovered from this analysis, which is sometimes a gap in testing methodology, but also very often a deeper, more serious bug than originally reported.

Truth is sometimes uncomfortable, and might include saying “My previous report was incorrect.” The person testing may work in an environment where saying that is safe, or they make work where admitting to a mistake sets them up for some form of punishment. Honest and valid testing should report the truth, and if the work environment does not support that, they have effectively decided they don’t want testing, they want something else.

Honesty and trust and commitment to truth must prevail

Software development is a social activity built on trust, shared understanding, due diligence, and pursuit of truth. How we respond to mistakes matters. We want to support the building blocks by doing the right work in reponse to the mistake, supporting each other in that work, and always reveal seek the truth.