Winning With Flaky Automation

Your flaky test automation is telling you something, and you better listen.

This article is my short version of how to deal with flaky test automation. I presented a long version at the Pacific Northwest Software Quality Conference in 2016. For those who don’t like watching videos, the paper is here.

My message is summed up in the hashtag #embracetheflake.

Measure, Fix, Separate

To succeed with flaky test automation, do the following:

- Measure the flake: for each test in the suite, run it repeatedly and calculate as a percentage the rate at which it gives you the same results

- Fix the flake: as much as you can, the flake is either in the product or in something in the test - do your best

- Separte the flake: there are two purposes and two suites - those that gate releases (high consistency, low to zero flake), and those that find bugs (flake tolerated, maybe even embraced)

If this makes sense to you then no real need to read further. Go back to your results and take action.

If it is not so obvious, then continue reading. I keep it simple here. My video and paper above provide far more material.

Flake = Inconsistent Results

Flake: when you get different results from executing a test multiple times without changing the test conditions

“Flaky test” is a misnomer. It might not be the test that is flaky. It might be the product. I prefer “inconsistent results,” or “flaky results,” but there is so much cultural momentum around the term “flaky tests” that I use the term to draw people into the discussion.

Inconsistent results frustrate engineers because it makes their job more difficult. But the results may indicate the product itself is flaky.

Tests that yield consistent results find easy to find, easy to fix bugs

The tests with consistent results almost all fit the following pattern:

- they have total control over the system under test and the test environment

- they are testing the smallest thing possible

- they are testing low-complexity, simple conditions

- they are checking for anticipated failures

- they only check for one specific thing

The bugs they find are critical, but also fundamental. These types of checks tend to be against functionality of the sort where if it fails the product does not meet its requirements at all. Were the check not there, the probability is high somebody would notice the failure anyway before release, but it would happen at higher cost.

Tests that yield consistent results are very good for fast running processes at scale that check whether code should proceed to the next process, such a submitting code to the repository, releasing to production. They are dreadful at discovering new bugs.

Tests that yield flaky results find nastier, more dangerous bugs

Tests with inconsistent results tend to fit the following pattern:

- they are unable to control some of the system under test or test environment

- they are testing large parts of the code

- they are testing high complexity behavior

- they catch unanticipated failures

- they check for many things, often implicitly

The product bugs they find tend not to get noticed until after the product is released. Something might happen 1/1000 times or less, and you don’t hear about them until there are enough users with product in hand to hit the problem. The bugs tend to be difficult to investigate, understand, and fix because they are the sort that slip by the developer as they work on the code. If they were easy to find, the developer would have seen them before submitting to the depot.

These sorts of tests also produce a lot of false positives. Failures that are not really product bugs. They are analogous to mining for gold. You sift through a lot of dirt, silt, and mud to find a nugget that returns a fortune.

Tests that yield inconsistent results tend to be very good at helping discover new bugs which will be painful to the customer and product team in production. They are dreadful as tools for gating release events.

Measure and Fix

Measurement is easy. The math required is simple percentages.

If the results are pass every time, then cosistency is 100%. If the results are fail every time for the same failure, consistency is also 100%. If the results are fail every time, but for different failures, consistency is the most count of most common failure divided by number of executions. If the results are less than pass every time, then consistency is simply the total of all failures divided by the number of times the test was run.

It is tempting to factor multiple failures into the the consistency in some sort of weighted mathematics, but simpler, chunkier measures make the problem easier. The goal is to identify the following buckets without too much fixation exact numbers:

- consistent: always yield the same result

- really close to inconsistent: numerically very close to consistent

- highly inconsistent: very far from consistent results

Fixing is more difficult. You probably want to take the following approach to choose what to fix in what order

- Identify the testing which is critical to make release decisions

- Find the most frequently occuring failure patterns

- Find the easy fixes from bad coding patterns in test or product code

The goal is to make a reasonable attempt at establishing consistency where it makes sense. Important checking that runs a lot should stabilize to bring costs down. Bad coding practices in test code and product code should be eliminated.

You are not going to eliminate all flake. You are going to eliminate flake that matters most so you can be effective at what comes next.

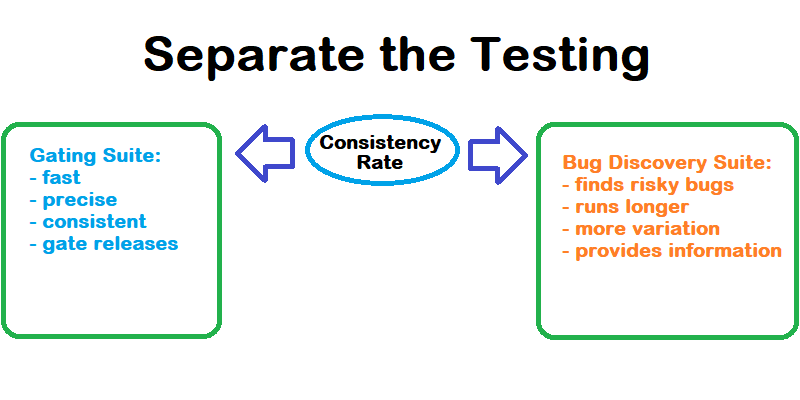

Separate the Flake

Divide your testing activity into two purposes, Gating, and Bug Discovery.

Gating Suites

Gating is for things like developer code submission, build validation, branch integration, and deployment pipelines. Gating suites run fast, run many times, fail with high cost, and should deliver reliable, clear, obvious information when they yield a failing signal. Failure in a Gating suite is the equivalent of pulling a brake. Checks in a Gating suite are looking for a reason for everything to stop and for someone to fix something.

Checks in a gating suite should have high consistency. Drive to zero flake tolerance.

Bug Discovery Suites

Bug Discovery is for finding failures not anticpated, not caught by other faster, more targeted processes. The faster a release process executes, the less room there is for bug discovery in the main pipeline, where execution may take longer to run, and failures longer to investigate. You will probably find the bug discovery suite is more useful when executed less often, in parallel to release pipelines. Use it as a source of information, a way to add issues to the backlog. If not on the main release pipeline, it would be up to a person to decide if something learned in the bug discovery pipeline warrants stopping some upcoming release.

While the tests in a bug discovery suite should represent engineering rigor and due diligence to stabilize the test behavior as much as possible, to some degree the unpredictability of the suite is what yields the high value bugs so well.

Checks in a bug discovery suite should optimize for coverage and finding failures the team fixes. Reducing flake tolerance is a secondary concern and may even be ignored if the trade off is finding more critical bugs.

Wrapping up the flaky

There is a lot more to cover in this topic. So much so that even this short version article is quite a lot to read.

The most important thing I want people to understand about flaky results is that the flake is information. It is telling you something is wrong. Too many people fixate on test code, abolishing any inconsistent result and test along with it to the rubish pile when they should be doing the opposite. The should measure the flake, fix what flake they can, and then separate their testing activities so consistent and reliable tests can help with the fast moving processes while the tests with the more interesting, admittedly inconsistent results, can help you find the really important, scary bugs.

As I said above, #embracetheflake.