Writing A Test Specification That Strays From Happy Path

Think Like a Tester and Intentionally Stray from the Happy Path

I share a story about writing a test specification directed specifically at straying from happy paths. What follows is part diary, part specification description, part musing about psychology, and partly about testing approaches. I share this because I hope it will help anybody reading this come up with ways of seeing beyond the happy path when thinking about testing.

I wrote a test specification this morning for some testing I want to try against a product I looked at earlier this week. I want to try to intentionally deviate away from happy path testing to see what problems I will find when doing so. The test specification is small, simple, was easy to write, taking only 68 minutes to create (I spent more time writing this article than I did creating the test specification.)

I did the following to force myself to stray from the happy path:

- Used prior accidental straying as a hint of where to go

- Looked at the features where “happy path”s were described, and made a list of their different usage modes

- Looked at the input data, and sought common ways of presenting the data that were alternatives to the happy path

- Built a list by combining the inputs and features together

- Left my test procedure loosely defined to allow variation and exploration on execution

This combination of rote idea combinations with loosely defined execution simultaneously forces me to consider ideas I might have skipped for not being happy paths while also giving room to come across unanticipated new non-happy path cases as I go.

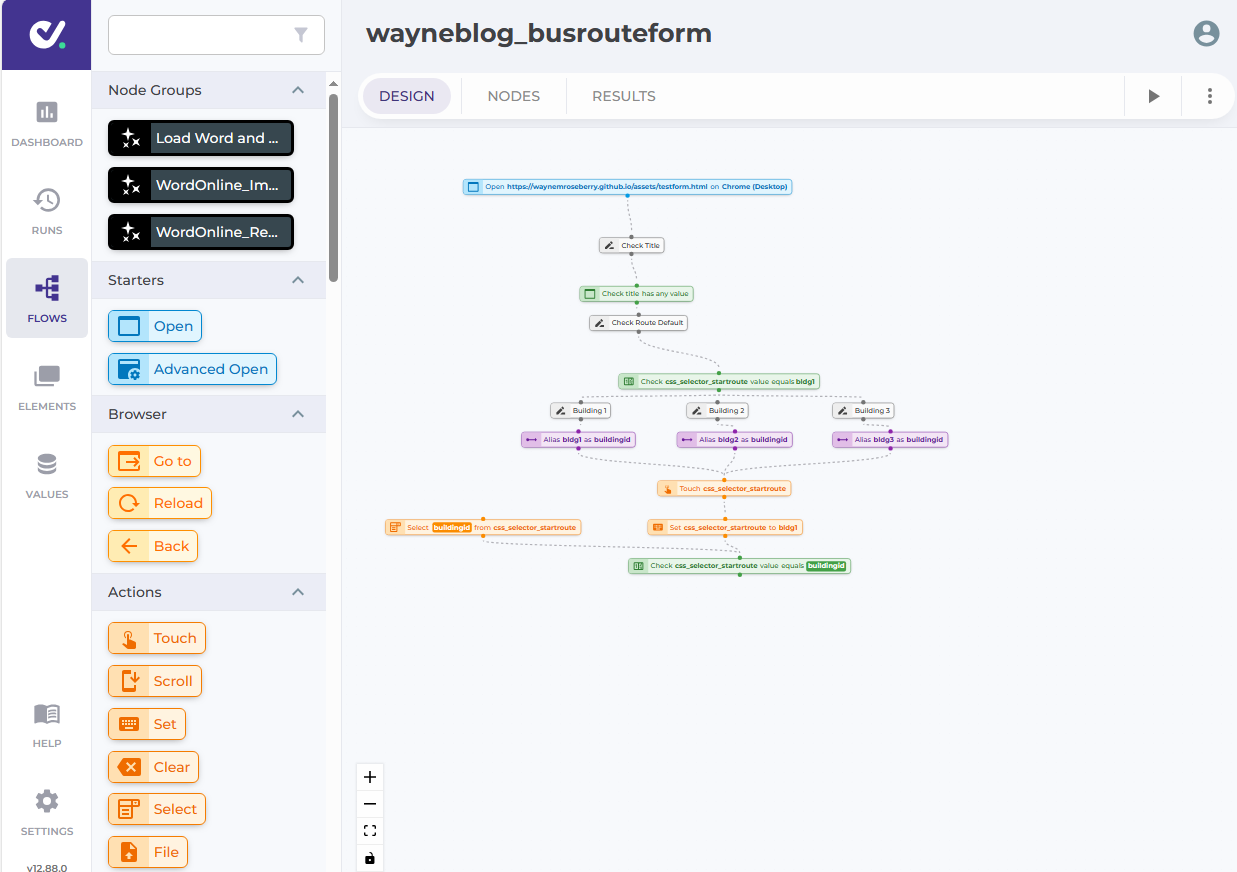

The product: DoesQA, a no-code test automation solution

DoesQA is described as a no-code

test automation solution. It offers a drag and drop graphic interface

for building workflows against web-based applications. The workflow

actions are tailored toward tasks which support automated checking,

such as finding web-page elements, manipulating and setting them,

checking their value, and a variety of other capabilities one finds

with similar products in this space.

I feel obliged to mention that all my exchanges with Sam Smith, a co-founder of DoesQA, were positive. He responded quickly to my questions, demonstrated interest and curiosity in the problem reports, and got right on fixing bugs uncovered during the explorations that preceded me writing the plan I describe in this document.

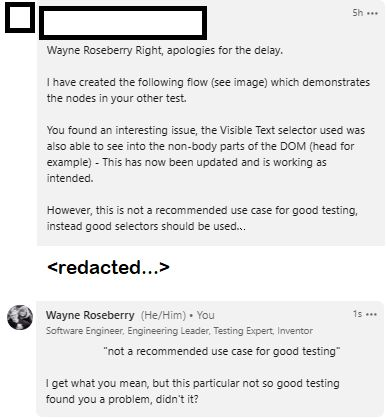

Selectors, and the happy path

I was giving DoesQA a free trial run, and had hit a problem with it failing to select a link on a page I created. I shared the problem with Sam Smith, a founder from DoesQA, in a post he had made on LinkedIn about DoesQA. He responded quickly, offering a different way to get to the element. In the reply, he indicated that the way I was trying to access the element not the way one ought to do it:

You found an interesting issue, the Visual Text selector used was also able to see into the non-body parts of the DOM (head for example) - This has now been updated and is working as intended.

However, this is not a recommended use case for good testing.

The fully reply is below.

Directed toward a customer trying to get the product to work, Sam’s comment is fine. An end user wants to solve their problem and get on their way. As a tester that same comment raises questions and concerns. As the response indicates, my prior attempt to use that selector had exposed a bug in the product.

What more lies ahead?

The “Stray from the happy path” heuristic

Products that work as toolboxes often face a situation where there are many ways to use the tools, and some of those ways are much better than others. Some of the ways may be undesirable, but are permitted because sometimes the users find themselves with no other choice.

When we make a tool, and we are checking that it works, we have a tendency to select the preferred ways to use those tools. We optimize for them, we look at them more often, we understand them better. They are preferred usually because everything lines up better with fewer unknowns, fewer problems to handle, fewer possibilities of exception.

This means that the code paths behind the less preferred use cases, those that stray from the “happy path,” have not been examined as closely. There are usually mistakes there that go beyond the reasons why the use case is not preferred. Often there are serious breaks.

As testers, we want to stray from the happy paths to find the forgotten parts of the code and observe what happens. The trick is how we get there. From the beginning, I stumbled on this case because I was testing against a web page that did not have good markup (lack of an id attribute on the element in question), so I took a shortcut and tried selecting based on element text. I did not intend to stray from the happy path, I just wound up doing it.

For sake of the testing, I want to stray more intentionally.

Methodically straying from the happy path

I don’t need to know every non-happy path action. I need some, enough to look for interesting failures. I use the following as a guide:

- My earlier Text Selector experience

- Prior knowledge that

- #id selectors work well, so everything else tends to be problematic

- ambiguous elements in a page require special handling

- selectors inside collections are problematic

- The DoesQA documentation tells people how to get selectors… so use that to see where it falls off

- DoesQA offers a set of options for referring to elements - use each one of those

I used the above to create a list of test ideas, created by combining DoesQA element selection capabilities against different actions DoesQA supports, against a set of problematic ways of referring to elements inside a web page.

Gathering the test data

Part of gathering the test data is a psychological balancing game. I am methodically building a list on the one hand to force myself to tread paths that I might mentally avoid were I being more freeform, but I am also forcing myself into some exploratory collection to introduce the possibility something I wasn’t intentionally thinking of slips in.

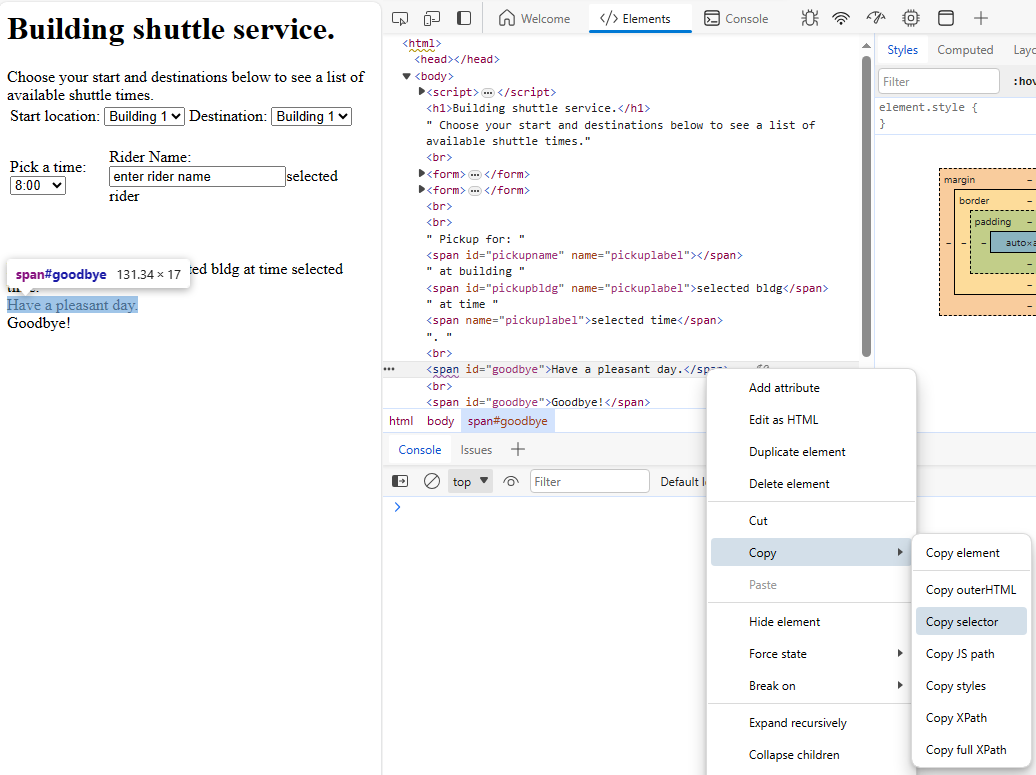

Web page selectors

I built a web page and published it to my website. Using my own web page gives me control over the page structure. I went with something very simple. Deeper testing could cover more complex page structures.

I used the following types of elements on the page:

- Forms, two of them.

- Tables, to simulate layout.

- Select lists, some with id, some without.

- Input box, without id.

- Spans that change in response to onchange events on some of the controls.

- Spans with static text with ambiguous ids in them.

That done, it was a matter of collecting different kinds of selectors for each of the elements.

I collected all the different selector types by loading the

test page into Edge and using developer view to collect the selectors.

I could have crafted the selectors by hand, but I wanted to follow

the documentation from DoesQA that advises people to use developer

view to get the selector strings. I did not want to fall into the

trap of writing strings that were too clean - or perhaps in the

opposite direction of being so poorly contrived as to be uninteresting.

By using a method that was close to the documentation I hope that

the bugs that come out of it are more interesting.

I collected all the different selector types by loading the

test page into Edge and using developer view to collect the selectors.

I could have crafted the selectors by hand, but I wanted to follow

the documentation from DoesQA that advises people to use developer

view to get the selector strings. I did not want to fall into the

trap of writing strings that were too clean - or perhaps in the

opposite direction of being so poorly contrived as to be uninteresting.

By using a method that was close to the documentation I hope that

the bugs that come out of it are more interesting.

DoesQA Actions and Element Types

I didn’t have a specification for DoesQA, but I did have documentation and the UI. That was sufficiently informative for this task. This part of the planning is rote collection of what DoesQA has to offer.

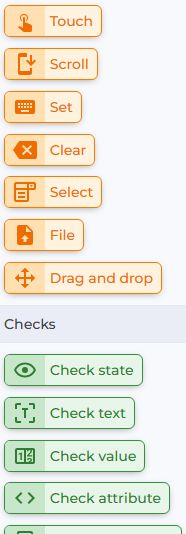

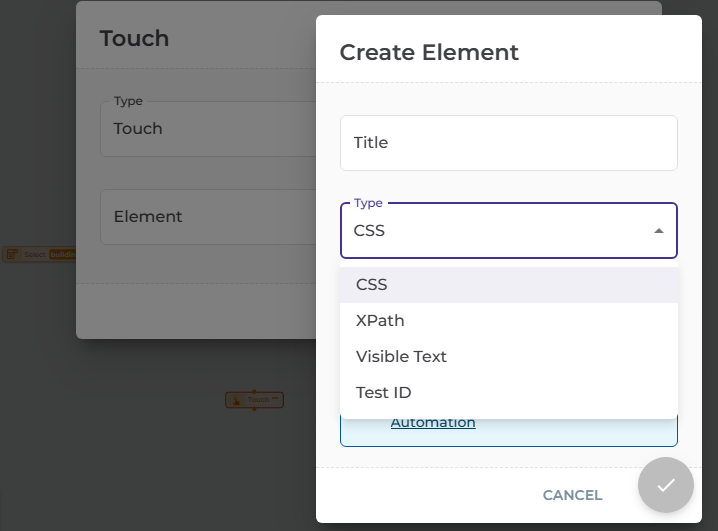

| DoesQA actions are displayed in a toolbar well on the left side of the screen. For this testing, I am focusing on Touch, Set, Select, and probably Check Value. |  |

|---|---|

| DoesQA element types are displayed when you select an action and indicate you want to define a new element to add. I am ignoring Test-Id in this testing. |  |

Buidling the workflows

I did not build the workflow as part of the planning. I consider creating the workflow part of the testing. I want to be in a testing mindset, looking for problems and recording them, while I create the workflow as well as when the workflow runs.

I also do not want to lock myself into a rigid script. I want to explore creating the workflow, trying different forms of it. Therefore, I have a rough idea of what I want the script to do:

- open the form webpage directly, don’t navigate in from top of blog

- branch from opening the webpage to a sequence for each element/selection string pairing

- in each sequence, check element initial value, touch it, set its value, check final value

Exactly what the flow will look like when I do that will vary as I explore. Very likely I will create more than one workflow to do the above as I notice differences in behavior that might expand the set of test cases I am working on.

My expectations are more implicit than explicit. The biggest one is I expect all the workflows to run to end without error. But there are other expectations. I expect to be able to create the element nodes using the address I got from the Developer view in Edge. I expect any errors I do see to be helpful and useful in a way that guides me to the correct thing to do. Beyond that, I am just looking for anything that sees odd or wrong. I have to go through a lot of supporting functionality to get to the test procedure, and I am keeping my eyes open along the way.

The test specification document

The test specification document is located here to look at. It is a short document with very few details. It was written to help me remember what testing I want to do, or to use when talking to someone else about what I want to try. It does not adhere to any formal templates. What it does include:

- A brief description of the testing problem and what motivated the testing

- A short breakdown of the approach

- Tables of the testing data

- A raw dump of the HTML in the testing form

For sake of this article, I also made a log of the time I spent creating the test plan, which was just short of 70 minutes. This includes everything I describe in the article above. It is a good idea to keep track of how long it takes to do something like planning. Sometimes an act takes far less time than we thought, and sometimes far more. It helps us get a sense of whether we are investing too much time on a problem, or if we need to do far more how much we might afford to do it. For example, let’s say we decided we wanted a much richer set of types of HTML documents and types of elements combined with different CSS and XPath ways of addressing them. If it was important, we might say “Instead of taking just an hour of planning, how about take a day to plan out the data set further…”

Recap on Finding Non-Happy Paths

Sometimes knowing how to do something guards our imagination from doing things a different way. That is a common outcome when as we design a product we anticipate, and design for, happy paths, preferred use cases in the code. We want to break out of that mode of thinking when we start testing, because we want to find the problems we did not anticipate. By forcing ourselves through rote combinations of the relevant factors in the test problem, a bit of research on which happy path alternatives are likely sources of problem, and building in some variance to allow for exploration during execution, we can formulate a plan that will help us see beyond our limited best use case viewpoint.

Now all we have to do is execute on that plan, something for a different article.