The Ai Created Solution That I Had More Fun Testing Than Solving

I had more fun testing this horseracing problem than solving it

The prompt for this image was “image of 25 horses working on a coding problem on a whiteboard.”

The fact that there are only 22 horses in the picture is in no way sufficient to ruin the

fact that the horse in front is standing on a ladder to access the whiteboard. I will take

innacurate any day if it comes with that kind of hilarious. Even funnier, all the computers in the

room are displaying the blue screen of death.

The prompt for this image was “image of 25 horses working on a coding problem on a whiteboard.”

The fact that there are only 22 horses in the picture is in no way sufficient to ruin the

fact that the horse in front is standing on a ladder to access the whiteboard. I will take

innacurate any day if it comes with that kind of hilarious. Even funnier, all the computers in the

room are displaying the blue screen of death.

I don’t mind a coding challenge, but sometimes I take longer than I would like to solve a problem. I do like testing the problems, and one that came up today had a nice, tiny little test method format which I enjoyed more than the problem itself. This is not, by far, an impressive bit of code that I wrote for testing something. But sometimes the small things are fun to share and talk about.

This one started as a post about LLMs solving math and coding problems. The original post proposed this question:

You have 25 horses.

5 can race at a time.

There are no stopwatches.

What is the minimum number of races required to identify the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd fastest horses in the entire group?

I and others engaged in a back and forth over how the different LLMs performed on this task. My observation was that ChatGpt gave a different answer every time I asked. Someone else noted that Bard got the answer correct every time.

I will provide the answer at the end, but I wasn’t convinced that the answer Bard gave was correct. I was pretty sure it was wrong. Turns out I was wrong, but I had fun finding out.

My failed quest to prove Bard wrong

I was pretty sure I could demonstrate what was wrong by testing the algorithm, but I had to write it first.

Implementing the solution

I wrote code that imitated Bard’s algorithm. The algorithm offered by Bard was in plain English (it was not asked to produce code).

Turns out the plain English version of the algorithm was actually incorrect. It was internally inconsistent with itself (I will include the full text at the end). I pointed this out, and the person I was conversing with offered their own clarification, which I accepted as what Bard was trying to express (I am making a huge concession to the AI to say it meant anything at all - think of it in a figurative sense). The algorithm I implemented was this fixed version.

I wrote the solution in a non-generalized way. It was hard coded to 25 horses, 5 horses per race, 7 races. I also wrote the solution so that it filled in the horses for heats 1-5 in the same order they were given to the method.

Testing the implementation

I created an interface to test against, and then implemented the Bard algorithm against the interface. In retrospect, I don’t like this interface, which I will talk about later.

public interface IHorseRacing

{

/// <summary>

/// returns number of races it took to find top three horses

/// in a set of heats.

/// </summary>

/// <param name="horses">an arry of horses with their relative times every time they race</param>

/// <param name="horsesPerRace">number of horses allowed per race</param>

/// <param name="finishers">1st, 2nd, and 3rd horses overall as identified by their index in horses array</param>

/// <returns></returns>

int TopThreeHorses(int[] horses, int horsesPerRace, out List<int> finishers);

}

An example of the test method is written below. This particular example is designed so that the horse timings are expressed in ascending order. There are some problems with this test code, which I will explain below.

[TestMethod]

public void TopThreeHorses_ascendingorder()

{

BardAlgorithm bard = new BardAlgorithm();

int[] horseTimes = new int[]

{

1,2,3,4,5,

6,7,8,9,10,

11,12,13,14,15,

16,17,18,19,20,

21,22,23,24,25

};

int fastest = bard.TopThreeHorses(horseTimes, 5, out List<int> outs);

Assert.AreEqual(3, outs.Count, "There better be three horses in there");

Assert.AreEqual(0, outs[0]);

Assert.AreEqual(1, outs[1]);

Assert.AreEqual(2, outs[2]);

}

The above is just one example. I had tests for ascending order, descending order, rotating the matrix, moving 2nd and 3rd place between different columns and rows in different arrangements.

And what I found was that no matter how I arranged the horses in the

input array, I got the correct winners in the array outs at the

end. As far as I could tell, the Bard algorithm was correct. At least for

the specific case of 25 horses in 5 horses allowed per race.

What I like about the test code.

The test code is easy to read. It is also laid out so that each row in source code for the array matches each one of the first set of heats. This is just a visual arrangement, but it makes it easier to understand the test case.

For example, in this different method excerpt, I have the order of horse times rotated so the fastest horses are spread across every heat:

int[] horseTimes = new int[]

{

1,6,11,16,21,

2,7,12,17,22,

3,8,13,18,23,

4,9,14,19,24,

5,10,15,20,25

};

And likewise, this example, which is the same as the first one, but the 2nd and 3rd place horses have been shifted by four heats:

int[] horseTimes = new int[]

{

1, 4, 5, 10, 11,

6, 12, 13, 14, 15,

7, 16, 17, 18, 19,

8, 22, 23, 24, 25,

9, 2, 3, 20, 21,

};

I like the way the matrix makes it easier to see what I am doing with the test data.

What I don’t like about the test data.

This problem didn’t occur to me when I was testing the Bard implementation of the algorithm, but it did when I wondered about generalizing the solution.

The interface as written doesn’t dictate 25 hours and 5 horses per race. It allows any number of horses overall, and any number of horses per race. The interface doesn’t specify how many races there will be overall, or how the horses should be distributed in heats.

The test code assumes there will be 7 races overall, and that the first

five races will be populated by going through the array horses in order.

The layout of the values in the test array is only meaningful if that

is true. If the algorithm implements a different strategy, the test

code layouts are just guessing.

I would prefer a different strategy, but that would mean a change in design of the method.

Let’s redesign this interface

Let’s consider these problems:

- The test is tied to the implementation

- The algorithm is in charge of the horse race outcomes, which is kind of like cheating

Consider the following change which creates a IHorseTrack interface and a Horse

class. The IHorseTrack implementation handles running races and communicates

the limit on horses per race.:

public interface IHorseRacing

{

/// <summary>

/// Runs a horse race derby. Manages the execution of heats to determine

/// 1st, 2nd, and 3rd place finishers.

/// </summary>

/// <param name="competingHorses">The horses competing in the derby.</param>

/// <param name="horseTrack">The track which will run the race.</param>

/// <param name="finishers">The 1st, 2nd, and 3rd place finishing horses in order.</param>

/// <returns>The number of heats executed for the derby.</returns>

int RunDerby(Horse[] competingHorses, IHorseTrack horseTrack, out List<Horse> finishers);

}

public interface IHorseTrack

{

/// <summary>

/// Number of horses per race allowed at track.

/// </summary>

/// <returns></returns>

int HorsesInRaceLimit();

/// <summary>

/// Run a horse race.

/// </summary>

/// <param name="horses">List of horses in the race.</param>

/// <returns>Array of the horses in finishing order, first to last.</returns>

Horse[] RunRace(Horse[] horses);

}

public class Horse

{

public string Id { get; set; }

}

The Horse object hides any information other than

the horse Id from the IHorseRacing.RunDerby method. The implementing object

cannot ‘cheat’ and lookup horse run times, or decide on its own which horse

ought to win a given race, as that is controlled by IHorseTrack.RunRace.

More important, this changes the test code so that

the array of horses doesn’t establish which horse

ought to win. Instead, the test method would implment a mock

implementation of IHorseTrack.RunRace and control from

there which horse places in what order in each race.

This starts getting really tricky. Anybody following this idea this far is probably anticipating a very difficult testing problem.

For a single call to

IHorseRacing.RunDerby(), we expect multiple calls to our mock ofIHorseTrack.RunRace. This means our mock has to be more dynamic, and it runs the danger of assuming a lot about implementation. How many times will our mock expect to get called? The horses may come in any number of races in any number of orders - what is it going to expect or consider a failing behavior? How will it decide which horses ought to come in what order to exercise different behaviors and conditions in the code?The more I think about this, the more I like the problem.

Back to the conversation

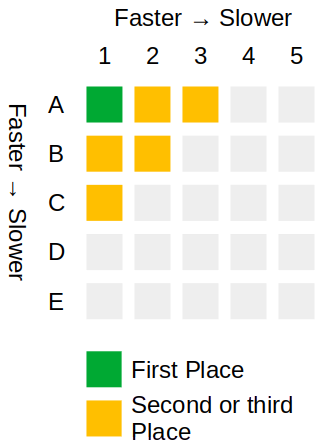

Some readers will want to know the algorithm, so I present it here as posted by John Elrick in this post from LinkedIn.

Identifying the top 3 fastest horses out of 25 with only 5 horses per race and no stopwatches requires a minimum of 7 races. This might seem surprising at first, but it’s due to the limitations of not knowing individual times and only having relative placement information.

Here’s how we can achieve this in 7 races:

Round 1: Divide and Conquer (5 races)

Divide the 25 horses into 5 groups of 5 horses each.

Run 5 races, one for each group.

In each race, identify the top 3 finishers (let’s call them A1, B1, C1, D1, and E1 for the respective groups).

Round 2: Winner of Winners (1 race) Run another race with all the group winners (A1, B1, C1, D1, and E1). The winner of this race is guaranteed to be the fastest horse overall.

Round 3: Pinpointing the Top 3 (1 race)

Now, we need to identify the 2nd and 3rd fastest horses. Here’s where it gets tricky.

Analyze the groups of the horses that finished 2nd and 3rd in the “Winner of Winners” race (let’s say B1 and C1, assuming A1 won).

Run one final race with the following horses:

The 2nd and 3rd finishers from the group of the overall winner (A2 and A3 in this case).

The 2nd finisher from the group of the horse that came 2nd in the “Winner of Winners” race (B2 in this example).

The horse that came 3rd in the “Winner of Winners” race (C1).

In this final race, the winner will be the 2nd fastest horse overall.

The horse that finishes 2nd in this race will be the 3rd fastest horse overall.

This approach guarantees that you can identify the top 3 fastest horses in 7 races. While it might seem like more races could be involved, this method cleverly leverages the information gained from previous races to efficiently narrow down the contenders for the top positions.

Remember, this is the minimum number of races required under these specific conditions. If you had more horses or could race more horses at a time, the number of races needed might change.

I argue, rightly, that Bard’s description of the algorithm if taken literally suggests 2 x 5 races are needed to determine 2nd and 3rd place, but with a small correction can be reduced to a single heat.

John offers in one of the comments an elegant, and gorgeous diagram of how you can determine 2nd and 3rd place in a single heat, which I have included below.

Why did I enjoy the testing more than solving the problem?

Maybe I wasn’t in a puzzle solving mood today.

But I think one of the reasons I liked the testing on this problem was because it was intriguing to ask what ways of arranging winners in horse races might confuse an algorithm trying to find the three fastest horses overall.

And it was fun to do this before I understood the answer. I tried immediately to think of boundaries and opposites, which in the case of a set of horse races is not as easy to define as one might think. So that was fun to do.

The other thing that I enjoyed was when I laid out the array elements visually to imitate the test idea I was going after. I enjoyed knowing that just looking at the code communicated why the test was doing what it meant. Meaningful pictures in the code, I guess?

It was a little disappointing when I realized how horribly tied to implementation details these snippets of test were - almost like all that visual elegance was in vain. I comfort myself by remembering that this was for a one-off hypothetical example. And also that the generalized re-design hints at an even more challenging testing problem. I might take that on in a later article.