Executing Non Happy Path Tests On A No Code Automation Service

Exploring the non-happy path on a no code automation tool

The prompt to Bing Image Creator was “A tester exploring a non-happy path test strategy on a no code automation tool”. The tester seems to be wearing what looks like a laurel wreath made out of beer can tabs on his head. And then all those gadgets, devices, and accessories all over the desk and floor makes me worry he is selling burner phones as a side hustle. I do enjoy that Happy is spelled wrong.

The prompt to Bing Image Creator was “A tester exploring a non-happy path test strategy on a no code automation tool”. The tester seems to be wearing what looks like a laurel wreath made out of beer can tabs on his head. And then all those gadgets, devices, and accessories all over the desk and floor makes me worry he is selling burner phones as a side hustle. I do enjoy that Happy is spelled wrong.

I recently wrote an article about creating a testing specification for covering some not-happy path cases for DoesQA, a no-code test automation service.

Today I executed the testing described in that specification. I sent a report of my findings to Sam Smith, a founder at DoesQA. In this article, I describe that testing. I am not employed or contracted by DoesQA. I was not asked to do this testing, I did it on my own out of curiosity, out of a need to exercise my skills, and to base this article on. I did have some back and forth conversation with Sam prior to and after this testing session, and he has been very friendly, cooperative and helpful.

The test report is located here. The raw testing notes are located here.

A few comments on my DoesQA experience

This article is more about how I went about testing DoesQa. But I also believe part of an assessment is sharing qualitative experience about the product. This is not a product review. I would have taken a different approach, looked at a more broad range set of use cases that would consider an engineer or team looking at larger scale processes and problems. My subjective experience is just a note of my feelings about the product.

I am reflecting on positive response here, as the rest of this article gets into testing, and the issues are addressed more there.

Things I like about DoesQA

I enjoyed using DoesQA. I had fun creating workflows and suites.

- The designer looks nice, and its graphical tools are easy to use

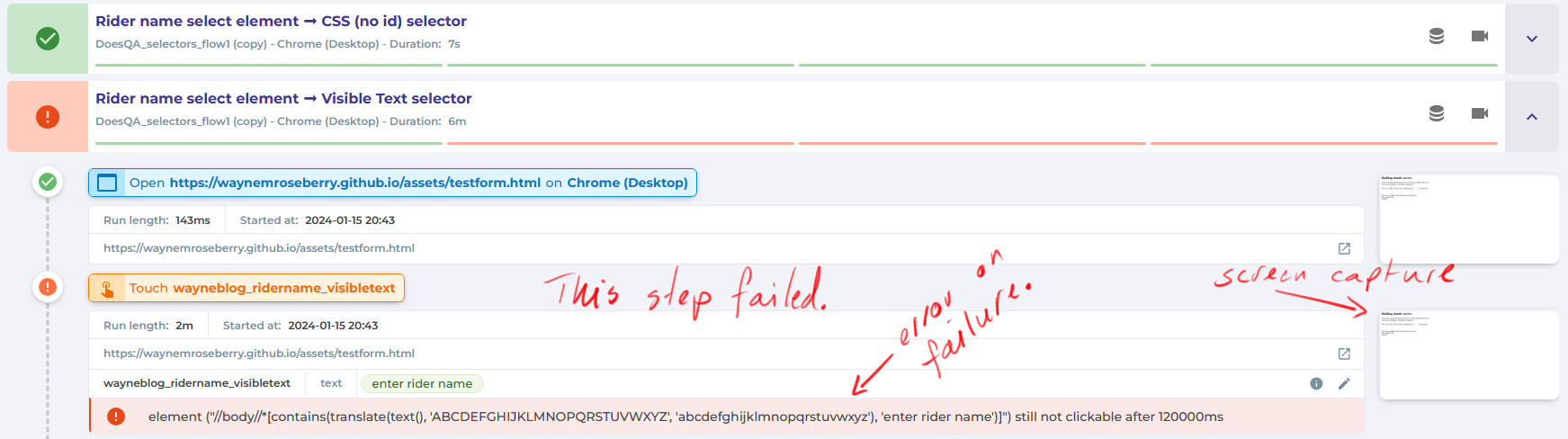

- The reporting page presents results nicely with errors inline with results

- Live status on results are nice to see, with the steps and stages represented as a horizontal line

- Per steps screen captures and video are useful

- The designer allows branching of workflows, which run as parallel jobs, and allows for fast creation of testing permutations

- The designer allows defining a collection of actions as a group that may be re-used like canned procedures

- Having a batch of machines in the cloud that just do whatever you want is a really great feature - common in this kind of tool, but very useful

My approach

I treated this as an interactive, end-to-end testing session. My charter was to cover different kinds of HTML element selection types (IDs, non-ID CSS selectors, XPath, Full XPath, inner text) against different types of actions in DoesQA (Touch, Set, Select, Check) against a few different types of HTML elements (SELECT, INPUT, SPAN, repeating, ambiguous, inside TABLES, etc.).

I was simulating a user creating simple control check workflows and then running them. I wanted to see any problems that came up while using the different types of selectors, because some of them had been described previously as non-happy path. I expected to hit some bugs looking in that direction.

I also wanted to leave room for exploration, so I went for a loosely structured approach. On the one hand I had a combination of variables I wanted to cover, but on the other I wanted to catch and investigate other problems that came up as I went.

I used only Word for my reporting and collection tools. I do not work for DoesQA, so I did not have access to whatever tools they use for issue tracking. I am used to working in Jira-like systems (Azure DevOps, my Microsoft legacy is showing), reporting the issues as I find them, but in this case I deviated and rolled up all results at the end. My bug reporting style is normally very “1-2-3… expected… actual”, but this time I found myself writing more of a story. That might be the effect of having to remember the problem an hour or two after the fact, maybe it was the loose, story-ish mood that Word put me in.

Testing Coverage and Method

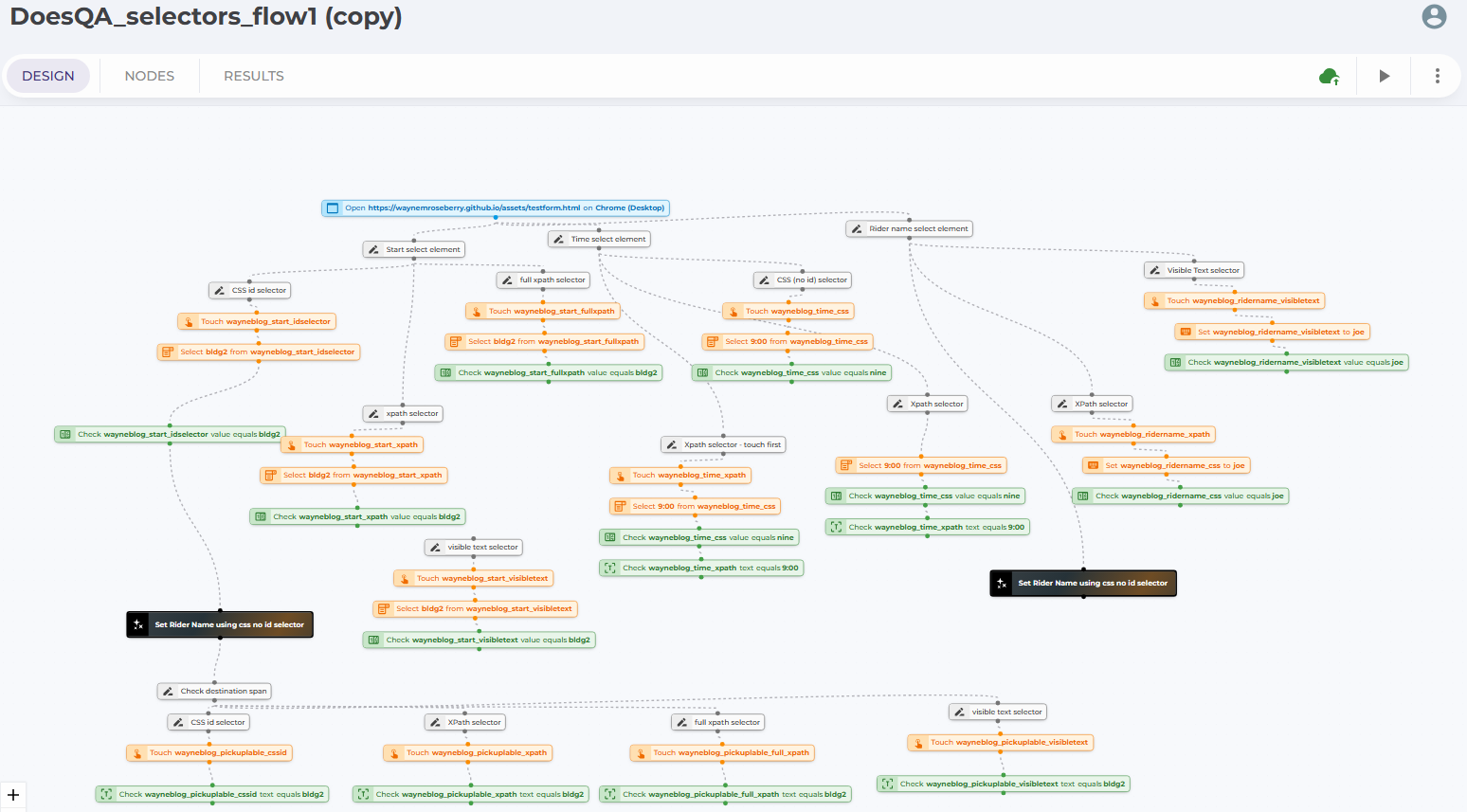

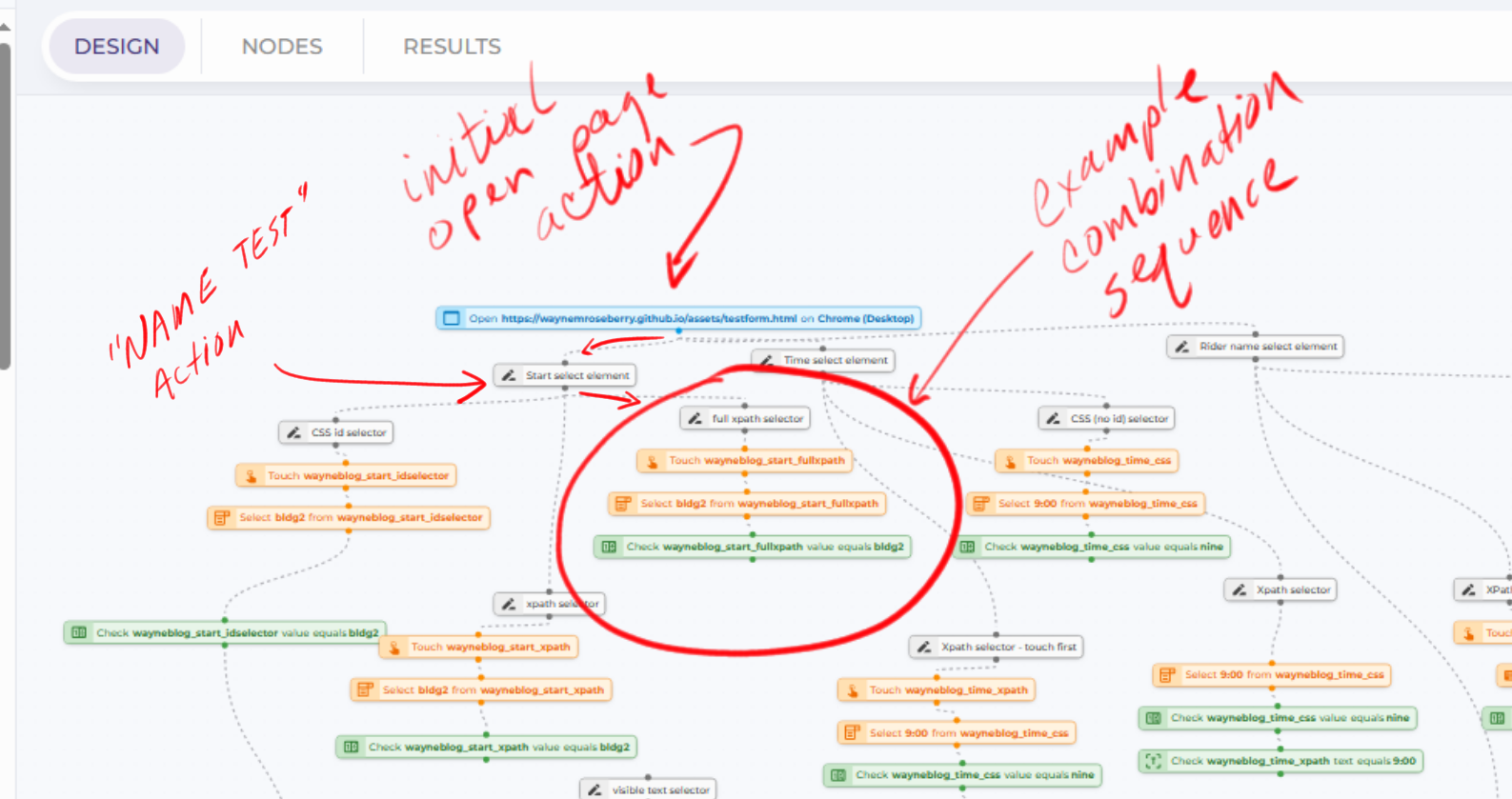

I covered approximately 13 combinations, give or take. They all are mostly represented in a single workflow, enabled by braches in the flow for each combination covered. One side effect of the way workflows are constructed is you can see a visual representation of the coverage. For the approach I took, every branch in the workflow represents a new set of coverage cases. You can see that in the image below.

I spent 2.5 hours testing, 2.5 hours preparing the written report.

My process per combination went like this:

- Create an open action to my webpage

- Place a “Name Test” action to label the branch, name it after the type of control I am testing

-

Place another “Name Test” action and name it after the type of selector (CSS ID CSS no ID XPath Full XPath) - Place a TOUCH action

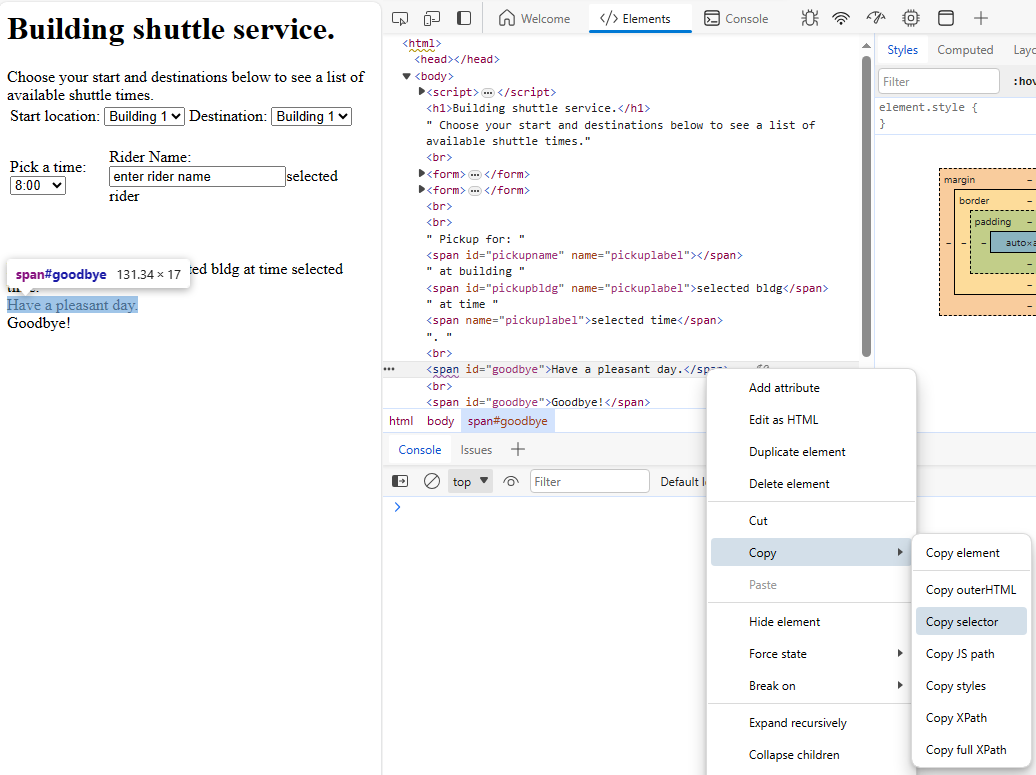

- Edit the action, Add Element

-

Copy the path to the element from the Developer Tools in Chrome

- Define the element that aligns with the type of selector in step 3 above

- Add a SET and CHECK action, using same element as defined above

- Chain/connect the actions together, to the two name actions, and up to the open action at the top

- Run the workflow

- Watch the run for errors or anything that doesn’t seem quite correct

I would then repeat the above for each combination inside the same workflow, creating branches that started with “Name Test” labels. The resulting workflow looked like the following:

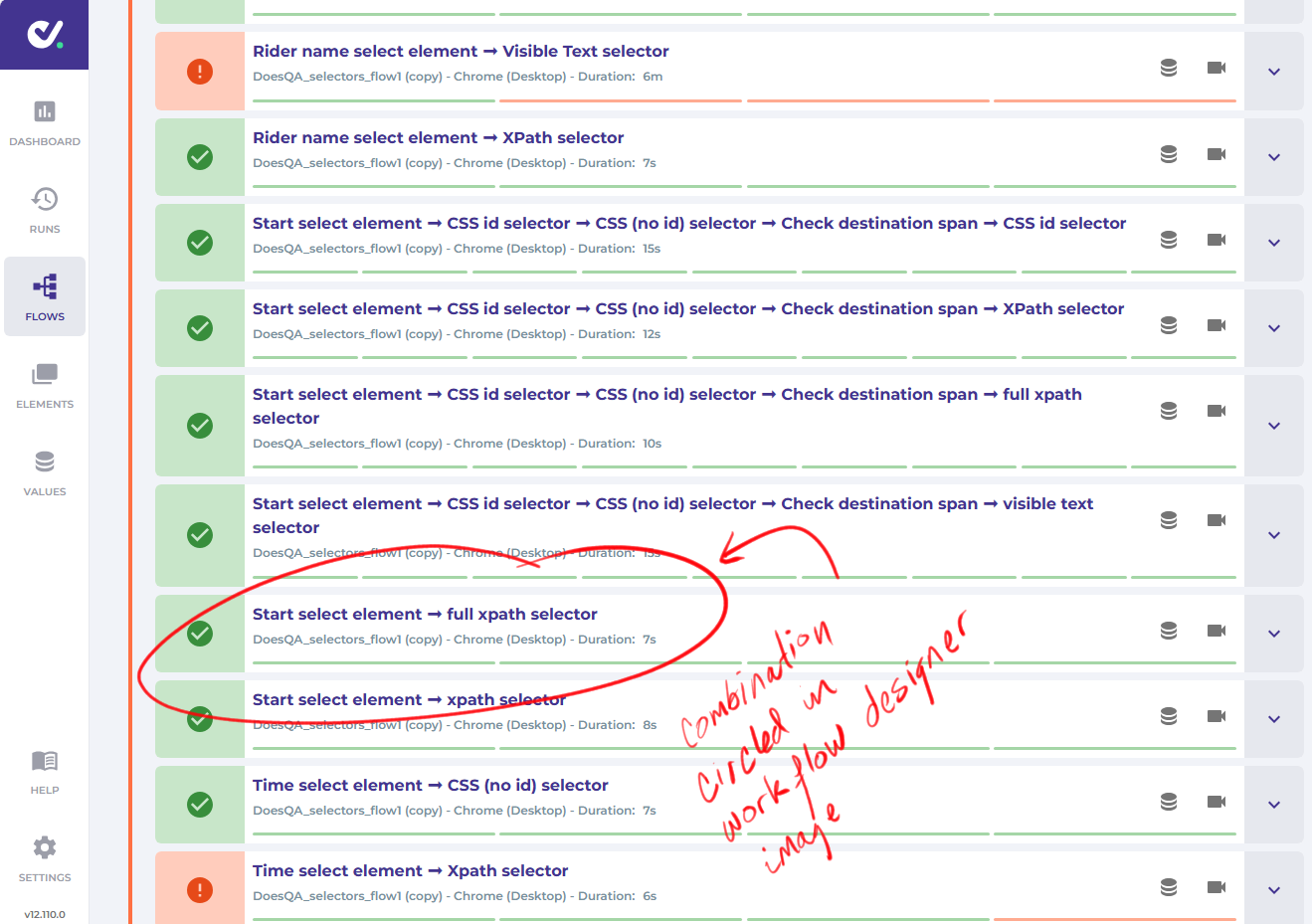

The “Name Test” actions introduce names that are catenated together during the run. This makes it easy to distinguish different branches in the results, as they run in parallel on any given job. An example result for the above workflow is shown below:

Errors are displayed in the results for the run, with information provided on each step. These errors were informative as I was testing, because I was very much interested in what the error experience was like. If the end user strayed from the happy path, how bad could things get? Are there any guides to get them back to the happy path?

The result below demonstrates such an examination. I was using the “Visible Text” selector to locate an INPUT element in a page. The error returned “still not clickable after 120000ms” was unclear, and led me to further investigation.

Keeping my head “clean”

It was a challenge to keep myself on the testing purpose, which was to find problems that come from building and running workflows using different types of selectors. I found myself sometimes wanting to finish and perfect the workflow I was creating rather than achieve the session charter.

This is a phenomeona I describe in another article, Integration Testing And Why Testers Are Not The Customer. In that I describe how when we cover a complex user scenario, we sometimes fixate on completing a correctly, well-working version of the scenario, and in doing that avoid any behavior that is not working well. Our interest is in doing the opposite. We want to keep looking into the behavior that does not work well so we can report on the affect they have on the product, user, and the business.

The main challenge on this front was when I would discover that a given type of Action would not work properly with a given type of element. For example, a “SELECT” element in HTML does not work well with the “SET” action in DoesQA, as the user is supposed to use the “SELECT” action instead. It was tempting, once learning that, to avoid that combination, but instead I committed to finishing workflows using “SET” actions with “SELECT” elements. I found similar awkward combinations, and made it a principle, a rule, that I would commit all the way to building an entire TOUCH, SET, CHECK sequence and run it. After doing that I would build a sequence with actions and elements aligned in a “compatible” manner.

This paid off, because while the runs would yield failing results as one might anticipate (thoughts on that later), the failing results were less than satisfying, giving the end user very little clue as to what went wrong.

Summary of Issues

I reported 14 different issues during testing. The issues are detailed in the test report document. A summarized list of them follows:

- Data Loss On Looping Workflow: If a workflow has a looping sequence, the designer goes into a “Saving…” state it never comes out of, and any subsequent edits to the workflow will be lost, with no warning or prompt, when the user switches away from the screen. I found this by accident. I did not intentionally loop the workflow, instead I inadvertently connected an action to a prior action on its chain while trying to tie two action sequences together as a branch to one of the longer scenarios.

- Lost Nodes During Edit: I had some nodes in the designer disappear while editing, but I never got a repro. I suspect it might have been the same problem as the looping workflow described above.

- Various Node Editing UI Clumsiness: There are some difficulties around control occlusion, connection editing, connection selection, node selection that are not extreme, but didn’t feel smooth either.

- Confusing errors and incompatibilities between actions and HTML element types: When the user specifies an action, or a selection type, that does not match the element they are trying to use, or the element state, the resulting error conditions are at least confusing and hard for the user to understand.

- Various UI issues and problems: Tab order oddness, ability to give things the same name without UI ability to distinguish, judgement call on the randomly chosen name scheme for runs, and other small problems.

In addition to the issue above, I offered a few feature suggestions. My favorite involves giving more power to the branching features to allow more re-use of actions across different elements.

How the “No code” product category affected my testing.

The product does claim to simplify automation, alleviate the user from having to use code, something I believe is misrepresented. I have other impressions about the overall “no code” automation category of tools and services, but I did not focus on that in my report.

I did use some of the product claims to focus on my attention to what I would consider a problem. DoesQA marketing claims target people with little to no technical expertise, almost as if business owners could derive workable, reliable, robust automation from use cases alone. Because of that, I put more importance during my testing on error state and how to get the user out of it. These are not end users comfortable with debuggers and web-traffic proxies and crawling the HTML DOM.

This story over, on to the next

This was a fun testing session. It was more like scenario testing, more like trying to imitate a user doing something, but it was guided by a set of combinations derived analytically. It created an interesting mix.

It was interesting reflecting on the test coverage and time spent in this session. My original specification had a couple of dozen combinations. I stopped at 14, with a few side trips for other investigations along the way. That much testing required 2.5 hours, and I was very disciplined about keeping my attention on just testing related activity. Writing the report also took 2.5 hours. Tracking exactly how much testing one does in a span of time, and how much supporting activity one has to do is very illuminating.

But I also feel very good about the issue discovery rate. I reported almost as many issues as the number of combinations I tried, with a couple of feature suggestions for a bonus. Only 13 combinations might seem small given the much larger possible number I could cover, but the defect density discovery rate paid off.

This was only my second experience using a no-code test autoamtion tool in the last decade or so, and I had been wanting to get a chance to look. I am glad I did.

I hope the story here, and the attached reports, are useful. Maybe you find something I encountered and share a similar experience. Maybe my approach is something you want to try. Maybe you see how I did this, and are groaning because you are SURE there would have been a better way. All good, as long as you take something away from it.