What To Do When You Need More Time To Test

When it feels like there is no time to test…

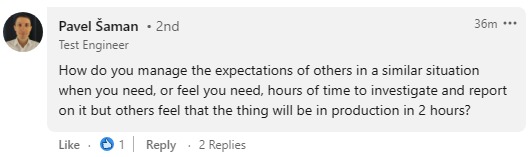

The prompt given to Bing Image Creator was “How do you manage the expectations of others in a similar situation when you need, or feel you need, hours of time to investigate and report on it but others feel that the thing will be in production in 2 hours?”, same as the question which prompted this article. I have decided the figure in the middle is in the middle of a breakdown, haunted by hallucinations that are increasingly violent, contorting office equipment into implements of harm. Hopefully this article talks them down…

The prompt given to Bing Image Creator was “How do you manage the expectations of others in a similar situation when you need, or feel you need, hours of time to investigate and report on it but others feel that the thing will be in production in 2 hours?”, same as the question which prompted this article. I have decided the figure in the middle is in the middle of a breakdown, haunted by hallucinations that are increasingly violent, contorting office equipment into implements of harm. Hopefully this article talks them down…

Someone recently asked me a question about testing time.

How do you manage the expectations of others in a similar situation when you need, or feel you need, hours of time to investigate and report on it but others feel that the thing will be in production in 2 hours?”

This was in response to an article I wrote of a test session where I spent 5 hours overall doing the testing and producing a report. I was working freelance, pro-bono, on the testing, so I was under no time constraints or deadlines. There was nobody telling me what I could or could not do, or whether my activities would have any affect on the product release or not. My situation was very different from a typical product team test engineer situation.

Real projects have constraints and obligations and deadlines that often limit how much time we have to complete something. Real projects are shared endeavors among multiple persons with different levels of obligation, responsibility, execution and decision making power.

In other words, sometimes the decision isn’t yours.

But I wonder if the question is the wrong question.

Is it about convincing people for more time?

It might be true that the situation was unavoidable. Something is delivered, the plan is that it should go in production in 2 hours, and somebody gets a look at what is going out and comes to believe at least another 5 hours of investigation in required. It might be a matter of changing minds in the moment.

If this is the case, then all you can probably do is tell people who own the decision your concerns, explain how you perceive the risks of not knowing what the investigation will tell you. Put the risks in terms that make sense to them, honestly represented in how they would perceive possible threats to the business or customer.

It is usually best to have this discussion in a written form so that decisions are on record.

After doing that, the probable possibilities are:

- You get the time you ask for, investigation commences

- No change is made to the product schedule, but you are allowed to continue the investigation

- You are told not to engage in the investigation

Another possibility exists which may or may not be avaiable to you. Just keep testing. The release to production may happen in 2 hours, and you might believe you need 5 hours to finish your testing. Test anyway. The release might not be waiting for you, but the information you offer, even in the worst case 3 hours late, may still be a big help to the team.

You don’t need to make it a secret. In a healthy work environment you should be able to say “I am going to continue testing, which I believe will take me 5 hours. Go ahead with the release. I will let you know what I learn, and if I see something really bad I will let you know as soon as I can.”

Let’s talk about power and responsibility

The question sounds like someone who feels obligated to the final product quality, but who does not have the power needed to affect the product quality.

Testing, the act of assessing a product, in particular toward threats to product value, via observation, is a different job than making decisions about how to create, change, build, or release a product. Some workplaces may give some testers some of those responsibilities, but in those moments the tester is really acting in a different job. Responsibility travels to power.

The tester responsibility is to test and deliver information about the testing. This includes reports about testing they believe should happen and the risks they believe that represents. When the tester has delivered their information, they have fulfilled their responsibilities in the tester role.

The obligation, likewise, is not to convince anybody of anything. The obligation is to give the people who make decisions the information they need to do so. Testers are there to make sure decision makers are well-informed. This is not a passmive submission, because the real power is that the tester gets to choose the information they provide. The tester owns that assessment, they own the tests they ran, they own the investigations they have made before, they own the analysis. Everything the tester owns represents a decision the tester made about what they believe is the right thing for the busines, product, and customer.

Is it about something else?

How does a change get all the way to 2 hours before going into production before somebody makes an assessment and believes there needs to be far more investigation before it can be released? Is this belief a surpise to everyone else involved? How long was this change worked on prior to this point? Who was told about the change, and were all the parties responsible for making the change, evaluating the change, deciding about release of the change included?

This question feels like it is about how a team works together, communicates, assigns responsibility, makes decisions, and manages product risk.

Some ways to consider this problem differently:

- Could the same assessment have been made earlier when there was more time to affect the schedule and plan?

- Could the testing, the investigation, have been conducted earlier?

- Are there changes to the product we could make that would reduce the investigation costs, risks associated, or break the problem up into smaller, manageable problems?

- Are there changes we could make to how changes, sprints, schedules line up that spreads the behavior across multiple submissions allowing investigation to span multiple releases as the change comes in more slowly?

- Do we have mechanisms to affect exposure control, feature light up, so that a roll to production is protected while testing commences?

What can the tester change?

It depends on what the tester controls. They may or may not own what they work on and when on a day by day basis.

Let’s pretend they do have more freedom to make decisions. Let’s pretend they know the rest of the team well, the PMs, designers, developer, release managers. If so, consider the following:

- get involved earlier and start making assessments before code even appears

- help the team construct a testing methodology that accomodates change with less debate over time right at release point

- help build a capability into your tools, product, and process, that supports managing test risk better

Some aspects of testing role goes beyond writing and running tests. Some aspect of it involves knowing and changing how testing is done, and that dovetails with the product and how the product is released and built. You may do some of this work on your own (at which point you are really taking on a different role than tester - which might be the right thing to do), or you may work with others to pull it off.

What do others change?

By “others” I mean somebody who is, at that moment, not testing. That may be the tester who has taken on work different from testing.

A possible list of changes are similar to the list of considerations above. A lot of the same things which help make testing easier also result in better product design, better capability for the business to scale, collect feedback, respond to change. Consider some of the following:

- start the communication process for change with all potential team members rather than just developer or product manager

- split tightly coupled dependencies with loosely coupled contracts between components and services

- build monitoring and telemetry into the product architecture with rich query and analysis capability

- build exposure control and feature gating capabilities into the product

- implement per change, feature, story, epic (whatever scheduling metaphor you use) team wide testing plans that take risk into account

- build into the release strategy how information about risk will factor into the release plan - what are the “stop now” indicators, what decisions gate different exposure level changes

There are more actions one could imagine, but each of these require people who own decisions to make them, who take action to take it. This would be designers, product managers, developers, release managers, business owners, or any of a number of other roles. Testers may contribute to this part of the change - and may own some of the actions, but in the case where the product code changes, or a business or process decision changes, if the tester is the one making that change or making that decision, they aren’t really in the tester role at that time.

Time to be done?

Concerns and questions about time for testing are often questions about power and responsibility. Testing is an information based job, and all the power and responsibility in that role is in discovering and delivering the information you can.

This might mean a tester finds themselves doing less testing than they believe should happen. The important in these cases is to provide the information so that all the team members have the information needed so everybody can take action and make decisions that make sense for what they are responsible for, for what power they have.