Build The Tester Mindset By Asking Is This A Bug

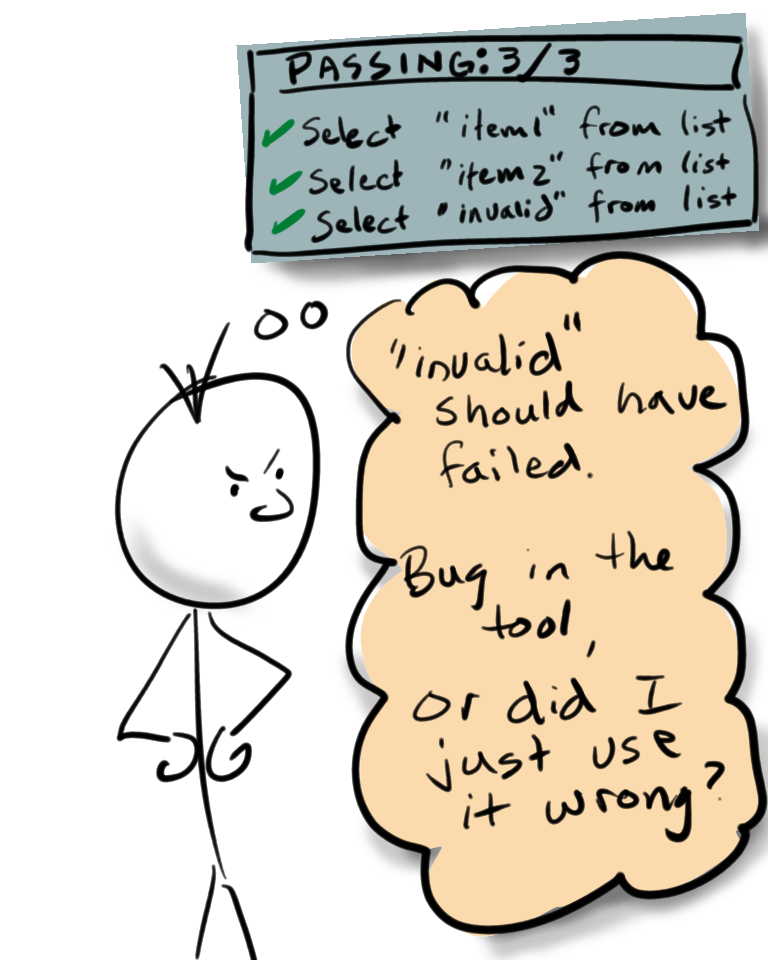

Is it a bug or not?

It is common when testing an application we observe a problem that we are not sure whether it is a bug. Sometimes we are uncertain whether the product code was meant to handle a certain condition. Sometimes we are uncertain if an existing product requirement addresses a given case. Sometimes our requires are more subtle, or inferred, or nuanced. Sometimes we need to understand customers, competing products, or the implications of the behavior more for the team to make a decision.

When testing, we want to help make these kinds of decisions by doing the following:

- use as much discipline and rigor and detail as possible when invetigating and reporting the behavior

- always report, even if you are unsure whether something is a problem or not

- investigate as many supporting sources of information as you can to help with the decision.

In this article, I tested DoesQa an test automation platform that presents a drag-and drop widget style automation editing surface for building tests against web-based interfaces. I directed the testing against a website I had built.

Example: Using a no-code automation solution to test a web application

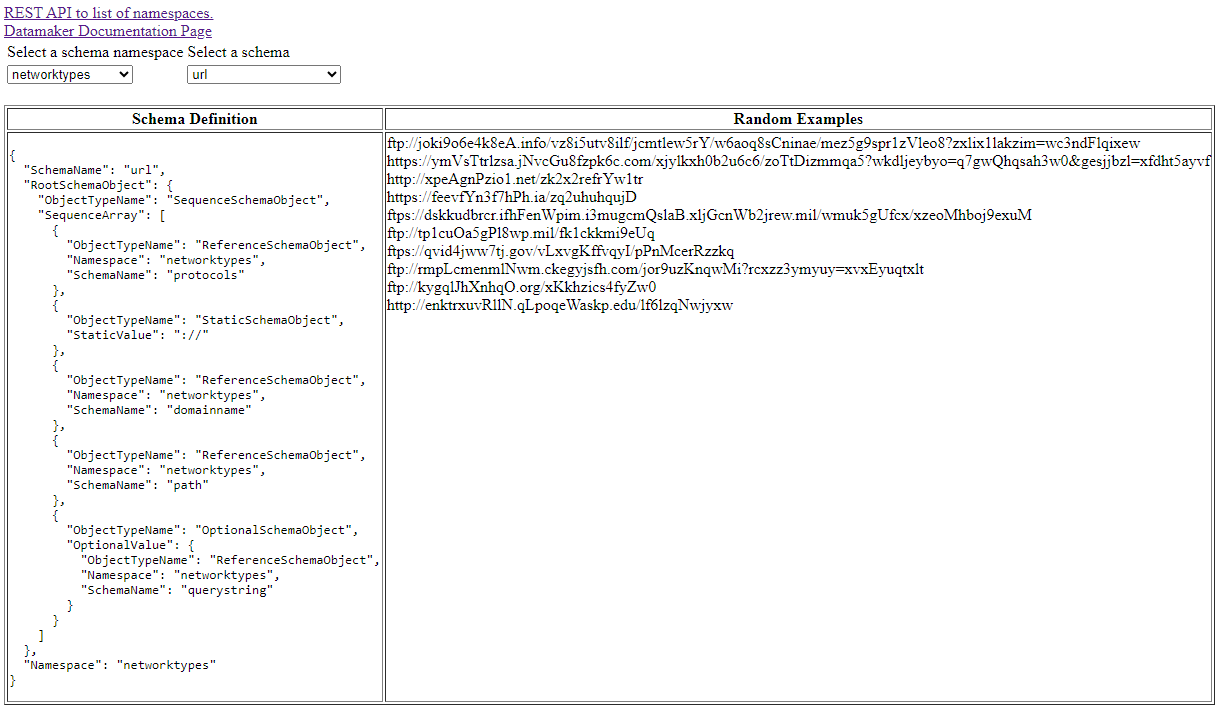

I have a tool called DataMaker, which at the time of this article writing had a rough and primitive UI. I used DoesQA to build automation workflows against this page.

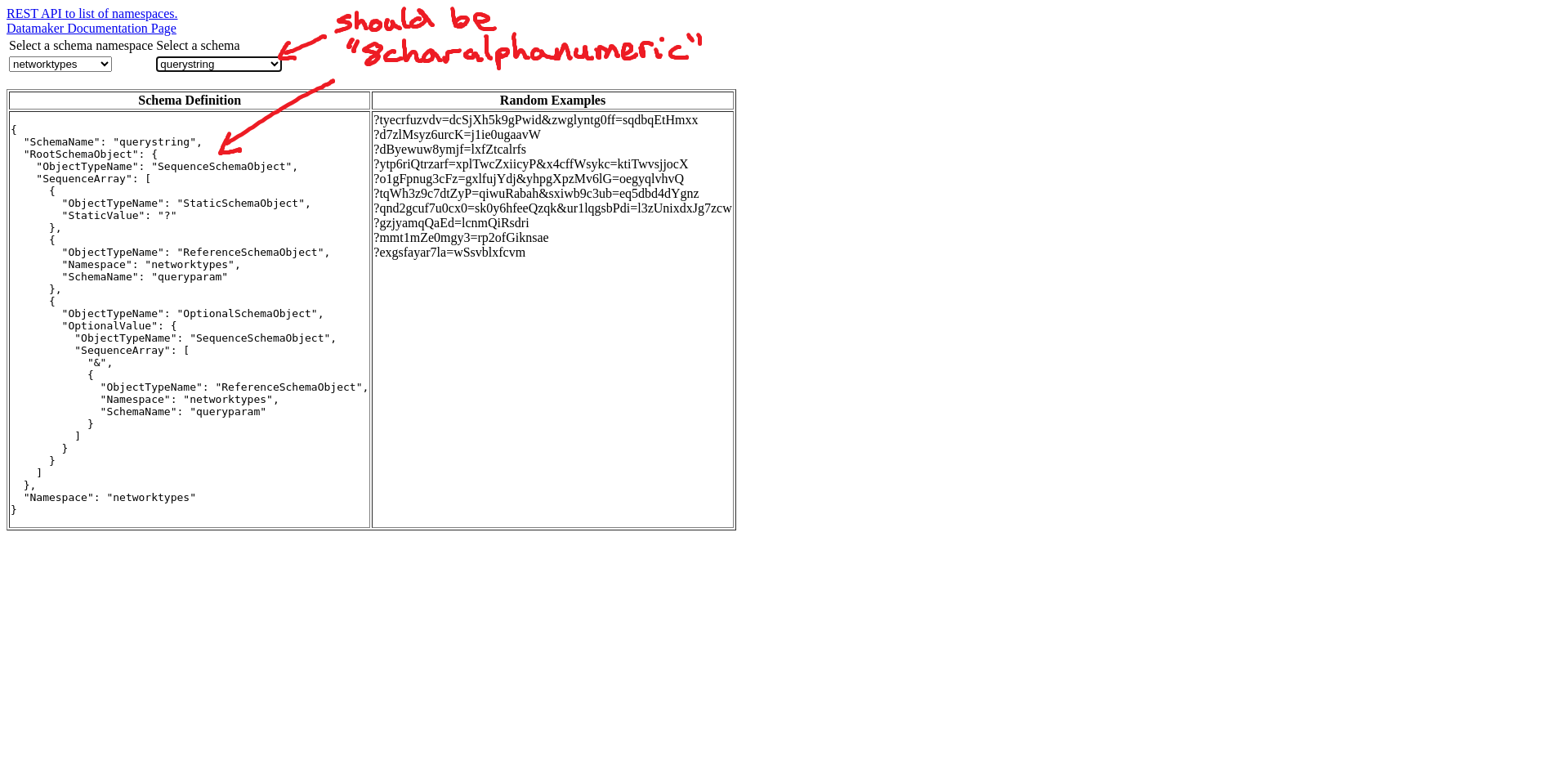

The page under test has two select elements and two spans of text. The first select element has a list of schema namespaces. The second select element has a list of schema definitions which change whenever the selected namespace in the first select element is changed. The two spans of text below are populated with data whenever a schema definition from the second select element is selected. The name of the selected schema definition should appear as part of the text in the first text span.

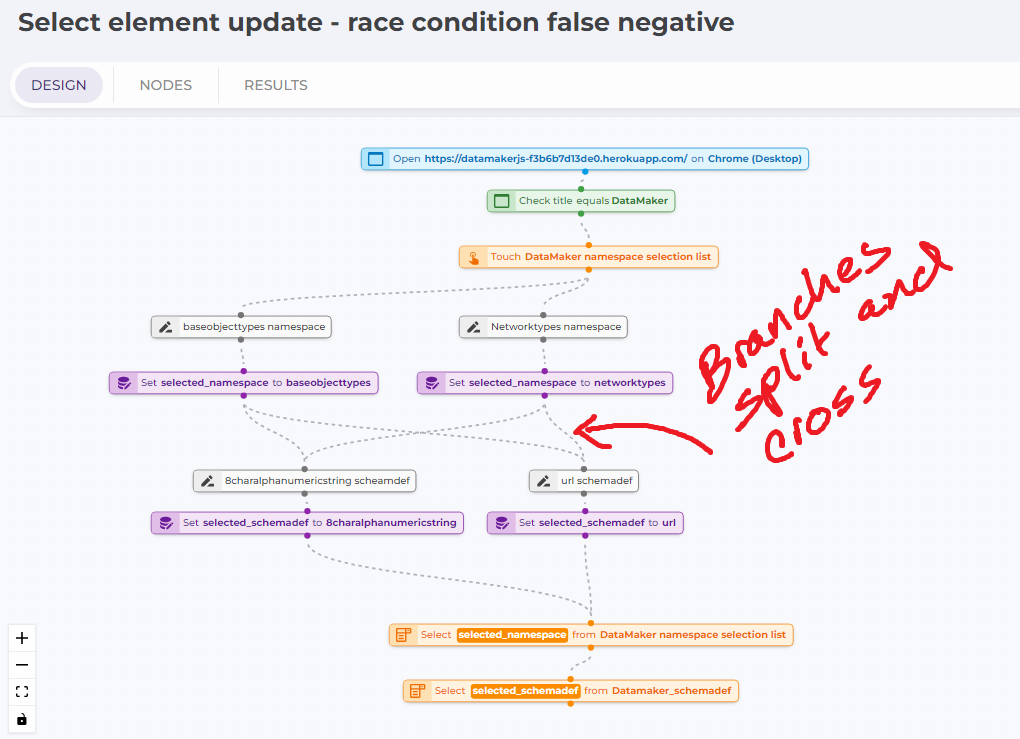

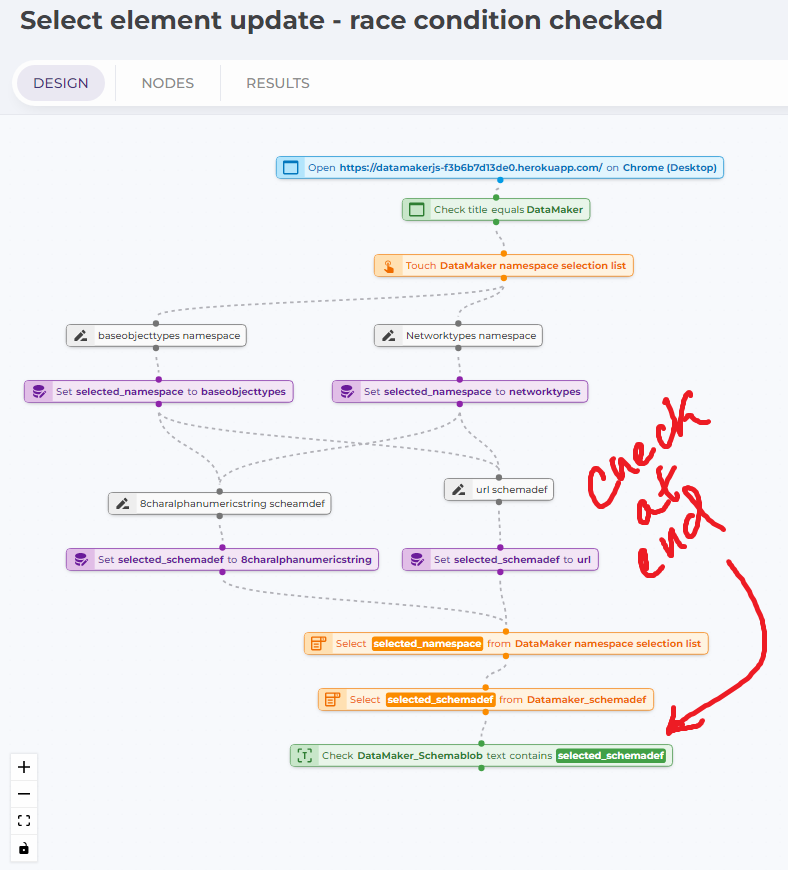

The worklow in DoesQA: trying different combinations of select list options

The flow in Does QA does the following:

- Opens the page https://datamakerjs-f3b6b7d13de0.herokuapp.com/

- Sets a variable called selected_namespace to a string value

- Sets a variable called selected_schemadef to a string value

- Selects selected_namespace from the

namespacelistselect element - Selects selected_schemadef from the

schemalistselect element

Steps 2 and 3 in the flow branch based on different values, allowing an easy mixing and matching of values for the script. The workflow as implemented has four combinations:

// baseobjecttypes is the default selected namespace in the UI

selected_namespace = networktypes, selected_schemadef = url

selected_namespace = networktypes, selected_schemadef = 8charalphanumeric // this is an invalid combination

selected_namespace = baseobjecttypes, selected_schemadef = url // this is an invalid combination

selected_namespace = baseobjecttypes, selected_schemadef = 8charalphanumeric

The basis of understanding a reported problem that may or may not be a bug is usually a detailed understanding of the product behavior. When possible, and when it makes sense, try to describe the behavior in precise terms so that the important and salient variables are understood later when making a decision.

With these combinations there are two valid settings for the select lists,

and two invalid. The expectation is that the branches/permutations of the flow

would fail on step 5 when attempting to select the selected_schemadef value

from the schemalist select element.

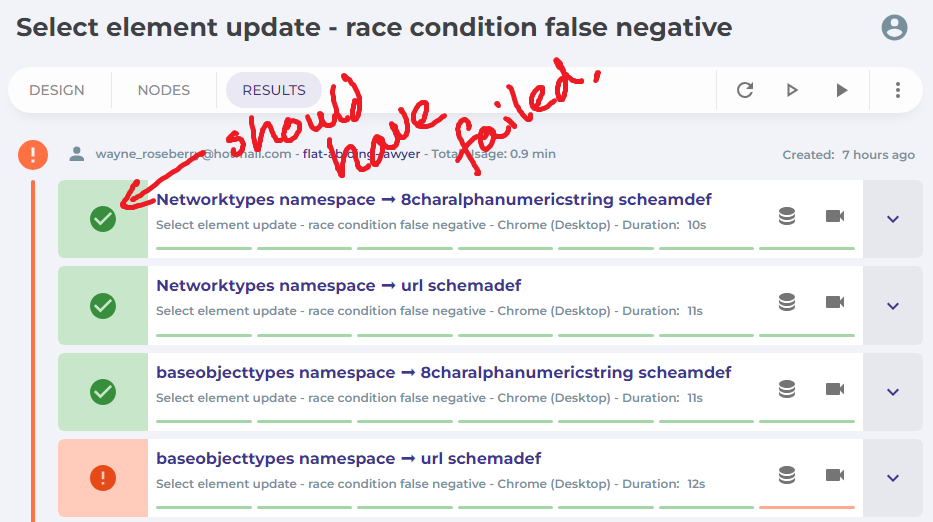

The expectations are met in three of the cases, (networktypes, url), (basojecttypes,url),

and (baseobjecttypes, 8charalphanumeric), which result in pass, fail, pass, as we

would expect. The case (networktypes, 8charalphanumeric) which should fail

when DoesQA tries to select “8charalphanumeric” from the select element

schemalist returns a pass instead. When we examine the final screenshot of the

run, we see that the value “querystring” has been selected in the itemlist

element instead of “8charalphanumeric.” This is likewise refected in the

text span below it in the leftmost table column, where the json of the schema

definition of “querystring” is displayed and not “8charalphanumeric.”

Why does the combination (networktypes, 8charalphanumeric) present a false

negative, a passing result, while its invalid option counterpart, (basojecttypes,url),

does not? The reason is because when “baseobjecttypes” is the default

selected namespace in the namespaceslist select element. Because of this,

the value “8charalphanumieric” is present by default in the schemalist selection element. From

the start of the script, the value “8charalphanumeric” is available to select, while the value

“url” is not.

What is happening?

As a tester, particularly one not on the project and with no access to the source code, I can only guess. The only evidence I have is from symptoms, things I can observe about the application behavior when the test method is executed. The evidence we have:

- DoesQA is told to select a value and it selects something else, but does not report that to us

- The value it is told to select had to be available prior to WHEN it makes the selection in order to get the false negative outcome

Reporting behavior, the result of testing, and finding root cause are two different activities. There may be multiple possible reasons why whatever you observed happens. Keep the behavioral description as distinct from speculation about root cause as much as possible.

This suggests a possible race condition where DoesQA attempts to select a value from

schemalist before the element schemalist is populated based on the onChange() event

of the namespace() element. But it also suggests a possible stale state behavior in

DoesQA where it is not updating its view/understanding of the page state before taking

action. There are other possibilities. Our description of the problem observation does not

need to get into this speculation. That is a follow-up, separate analysis. What is

important is that the test result is accurate and not tainted by speculation.

When testing we want to describe the symptoms and necessary conditions to get to the symptoms as completely as possible. Diagnosing exact behavior, tracing to root cause is a different activity. It is not a bad activity to do at test time, but one does need to have the code available to them to do it.

Is it a bug?

My rule of thumb when I find something is to report it regardless. If you are uncertain if something is a bug, ask how the team feels about it. Explain why you are asking, why you believe it might be a bug.

Always report your findings, especially if you are not sure something is a bug, is a problem or not.

The behavior I found in this case may seem like an obvious bug to some people, and might sound like expected behavior to others.

The case for it being a bug

The case for it being a bug is that one might expect that if a tool is told to select an item that is not available, it should fail the operation with an error. Taking the action without reporting leads to the impression the operation succeeded the item was not available leads to a false sense of what state the application is in.

This case is further supported by some of the claims on the DoesQA website:

Code has bugs. Don’t add more!

Rapidly expand test coverage with reliable codeless test automation.

and…

Create complex tests in minutes - not days - and run them in seconds with 100% reliability!

It seems rational to consider false negatives, passing results when the tool did not actually do what is was asked to do and the application is not in the expected state, less than “100% reliability” and it certain feels as if with a false negative bug in the test we did just “add more” bugs.

Consider the claims about the product behavior in both direct and subtle ways. This is challenging because being overly legalistic on the wording of a claim can be just as misleading as being too broad on its reading. We can fool ourselves into being too generous or conservative when deciding whether something is a bug.

The case for it not being a bug

DoesQA competes against lower level coding languages and libaries for

creating automated tests. It is very likely that somebody writing the automation

using the same steps I used would hit a similar problem. The script, as I wrote

it, does not allow for checking if the schemalist element has updated

yet before attempting a selection. It does not check at the end if the page

updates with the expected value for the json definition of the selected schema definition.

I implemented an alternate version of the workflow which adds this check at the end, and the flow returns a fail, as it should, when different values are found in the schema definition json.

Compared to other lower level language solutions, the burden has always been placed on the author of the automation to recognize that driving UI based automation always requires more explicitly checking, dealing with timing delays, and relying less on implicit behavior assumptions to navigate the UI in a controlled fashion. Proper use of the toolset demands a body of domain knowledge, keen awareness of the tool behavior, and being a skilled programmer.

The behavior in DoesQA might be indicating no more than what we might expect out of any other end to end UI automation coding langauge.

When whether a behavior is a bug or not is uncertain, it is good to understand the reason why it might not be a bug. Try to represent that argument as best you can, as fairly as possible.

How do you rationalize the whether it is a bug or not?

The only thing you can do is make a decision, and from the testing perspective, we provide information so the people responsible for that information can make an informed choice. There are some points to consider:

- Does the product intend for the behavior to be different than reported? Does what you reported violate an intended requirement?

- Does the behavior reported match or violate claims made about the product? Some of these claims might be specific, some of them might be subtle and nuanced.

- Do we know how end users are likely to use the product and what they would expect in this situation?

- Does the behavior present a problem, for example the ways the end user might workaround it, that the business would want to avoid?

- Is there a similar behavior in a competing product, and what does it look like?

For all of that, whomever is testing has some work to do.

Collect some of the following information and present it in the testing report

- product requirements: refer or repeat the relative requirement, and explain how or if the behavior is a direct violation

- marketing literature, demo material, documentation: if the product is released, there will likely be something, if it has not, this might be a chance to change up the literature before release if the behavior is something you intend to ship

- try same thing in a competing product: is the experience similar, better, worse, completely different in the competition? Sometimes this information makes a very compelling case for the decision

- find examples of end user behavior: support forums, user groups, articles, customers you have existing relationships with, sales and market representatives, support staff.. any of these may have more perspective, information that could help frame the report better

Violating a requirement, an intended behavior, is usually a good indication what you found will be determined a bug. That is usually easy, and unusual the team will decide otherwise, but they might.

Let’s pretend (I don’t know right now, although I do have a communication going back and forth with Sam Smith, co-founder of DoesQA) that there is an explicit requirement that the “Select <value” action is meant to encapsulate timing and race condition logic on behalf of the automation author so they do not need to mitigate such situations with waits or between step checks. If such a requirement exists, this behavior seems an obvious violation of it, and I suspect some developer would be on it quickly to figure out how this condition got past the code.

Violating subtle claims about a product behavior are a more difficult decision. DoesQA presents an interesting subtlety in its claims.

There is an implied claim about the product that using DoesQA is so much easier because the programming skills are less (zero, if you take the hyperbolic “no code” term literally) than in any other language. The literature boasts speed, easy of use, increased reliability.

What this behavior demonstrates rather effectively is that the burden of understanding the subtle mechanisms of web-based UI automation is no different and challenging on DoesQA than any other language. You still have intricate timing and state problems to manage. You still have to make a choice between trusting your actions and checking every step along the way. You still have race conditions, delayed updates, tricky data and content to compare accurately to oracles.

But counter to that, it is perhaps unfair to expect a problem be solved that competition hasn’t solved either. DoesQA makes automation easier in ways the lower level languages do not (FWIW: despite me bluntly reporting the bugs I find, I find the drag and drop editing style of DoesQA enjoyable and easy to do). Perhaps there is a “come back to reality” moment the customer needs to have after they put down the brochures and marketing slicks, but it is a familiar journey a lot of other automation programmers have been through, so it winds up being no worse than most of the competition. The “workaround” in this case is, in another tool or language, just considered “better coding.”

UPDATE: Responses from Sam Smith at DoesQA

Sam responded to the testing report, and his team did quite a bit of investigation of the reported issue. I am going to summarize his response rather than put it verbatim, as my goal is to share the testing experience and convey how these kinds of issues foster a communication.

- There was a bug involved in the false negative case that has to do with how select action behaves, and the team already made one fix live, others planned.

- There are other ways that the select action presents options for setting/checking values which lead the user toward less stable design ideas, and the team is making changes around that as well.

- Passive action based on implicit assumpts rather than confirmed, checked state, is an automation anti-pattern (the use case in my article is an instance of the anti-pattern), and DoesQA has some features (existing and planned) to coax, encourage, and train the users away from this anti-pattern.

- DoesQA both wants the controls to robustly do what they say the are going to do, and also expects its users to apply similar principles of robust automation engineering as they would in any langage. It is not DoesQA’s goal to magically make that requirement disappear. As per the point above, they want to make it easier for the end user to know how to do the right thing.

I put this section in as an addendum rather than re-write any of the rest of the article because I wanted to capture a semi-real-time account of my statement of mind both before and after talking with Sam. If you read the bullet points above, and then read my musing on possibilities from earlier, you will see my speculations are partially correct and also partially wrong. But the information about what I observed during testing was valuable to the team.

Among other things, testing is a conversation. It also drives a change in understanding for everyone involved. The creators of the code learn things about code behavior they did not. The person testing learns something based on the response to test reporting. Optimize for this conversation, optimize for learning, and you will optimize for better outcomes.

Are we done or not with whether it is a bug or not?

Just like with whether something you find in a product is a bug or not, we have to make a decision. Part of that decision was yours, and whether you read this far or not demonstrates you at least decided you were not done until reading this far. For myself, I want to at least summarize my points.

Whether something is a bug or not is a decision. That decision requires information. Testers supply that information based on our observations about the product. We do not hold that information back, afraid that the decision might be “not a bug,” but instead, we report the information anyway. We apply rigor to our testing, our analysis, and our reporting so the decision is made with as accurate a set of information as we can manage. If we do that much, we have done the best we can, and will probably anticipate more accurately and more often how the customer perceives it.