Thinking Like A Tester By Keeping The User Story Going

Keep the story growing…

One of my favorite test techniques is scenario testing. Find a problem the end user is trying to solve, use the product to solve that problem, and report any issues or bugs you discover along the way. This aligns well with most software development approaches, which tend to align requirements around use cases, user scenarios, user stories, and a variety of other labels that tie requirements to something the user wants or needs.

A note on the testing activity

I am not an employee of ContextQA. I was not paid or compensated by anybody at ContextQA for performing this testing. I shared the testing report I describe below with Deep Barot, founder of ContextQA. He has also read this article prior to me sharing it online.

These ideas tend to be captured in small little nuggets. For testing, we often want bigger.

I performed a scenario testing session against ContextQA, a no-code test automation platform that provides record and playback and self-healing support. A report from this session is located here.

I started small:

An engineer needs to create an automated check for modifications to the web application their team is building….

The above would typically provide more details, but the starter here is enough to capture the idea that we tend to work with small stories. I chose the above story, and then extended it…

An engineer needs to create an automated check for modifications to the web application their team is building. The engineer intends to save time so they use a web-session recorder to capture their steps in a script. The web application is undergoing changes in its visual layout, and the same scripts are used to check changes as they are submitted.

I bumped the story up. The first bump would likely be found in some form in the list of requirements, and while it violates some rules of not including the solution in the story, it captures the idea that the end user in this case is trying to avoid writing the scripts themselves. This is part of the value proposition of the product in quesiton. I don’t need to adhere to design principles here, I just need a story to inspire some imagination and testing activity.

The next bump is something derived from the product marketing, claims and promises of robust and reliable scripts. I want to imagine different ways we exercise that claim. One of the most important factors that affect our relationship to automation scripts is changes in the product under test.

Oh… I forgot something…

The web page is written in a way that is not well designed for automated scripting.

This is another extension of exploring the value claims of the product. One of the features of this tool is automatic self-healing, built-in intelligence that intends to make scripts more robust. That is pretty easy when the web application is well architected for testability, but when it is not, what happens?

How do you grow the story?

Let’s break down an approach. Truth is I don’t really do this by breaking it down into steps. I intuit the final outcome. But internally, it is essentially something like the following:

Start with a basic user story

These can come from anywhere. You might have user stories as part of your project. They might be in a Jira ticket. They might be in a list somewhere. If your team does not explicitly track user stories somewhere, look at other sources of information. Marketing materials and end user documentation/help content is one source. Recent product demos are good. Is there a body of training and how-to videos online from the company or even end-user consultants and enthusiasts?

You just need one story. For example: In the test session I used for this article, I took the story as implied by the ContextQA website product promotional claims.

Think beyond the moment of the story, build a context

The stories you will find are almost always very isolated and sanitized. This is because the stories are easier to use and fit their purpose better (to sell, to educate, to illustrate) if they are simpler. The optimum, simple case works better for these stories the way everybody else uses them.

The truth is our the user’s situation is rich and complex. Pointing our intent to simple versions of that situation may be an effective way to achieve clarity and focus, but our success relies on complementing that focus with discovery of the exceptions and conditions that complicate the story. When you test, you want to capture some of that context in its more complicated, rich, unpredictable way.

Ask questions, such as:

- what data does the user have available to them?

- what process, work or other activity preceded this story?

- what does their overall workplace, or system look like? What state is it in?

You don’t need to imagine every possible change to the situation. You don’t need to imagine a complete and thorough description of the context. You just need enough interesting variations - sometimes only one or two - to make the testing reveal something unanticipated and new.

For example: In this testing session, I pointed ContextQA at a website I have been building indepenent of this testing initiative. It’s problems and bugs are real because it is still rough, still under development, and I actually have a real purpose for the site.

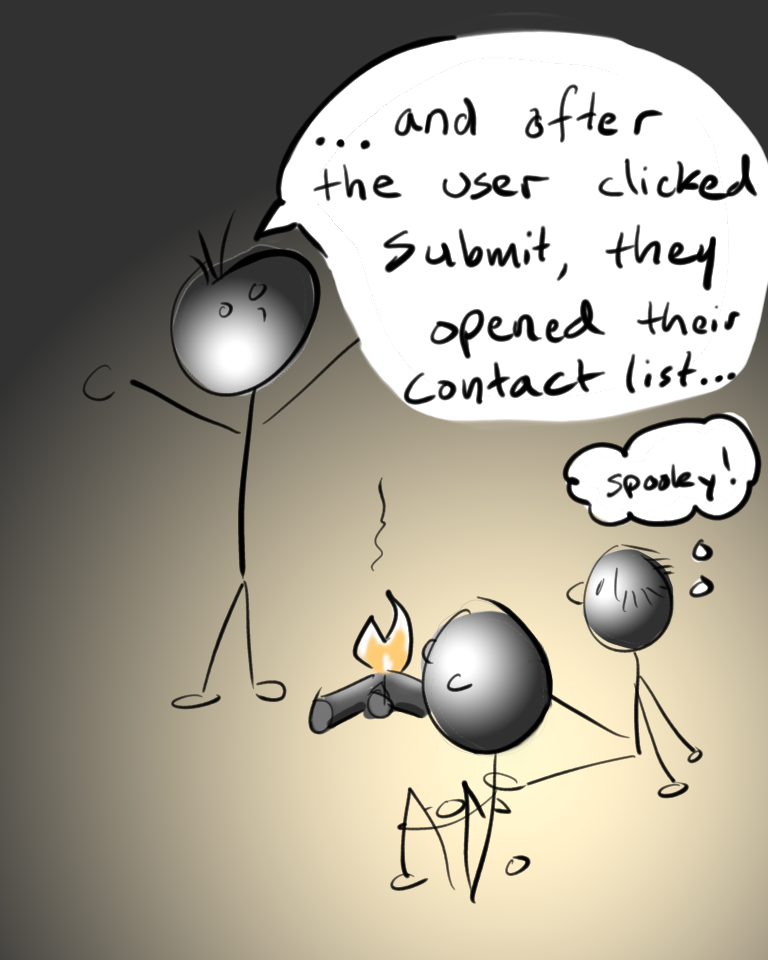

Search for the “Yes, and…” opportunities

Just like the situation in the user story tends to be sanitized and simple, so to are the actions the user takes. The “what next” is almost always a linear path to a singular point of anticipated success. There are no deviations, distractions, interruptions, and somehow at the end of the story, the user is left whole, satisfied and fulfilled. Everything done, story over.

Real usage is frequently very different. Users abort the sequence to collect information elsewhere or check state. They want a slightly different behavior than the simple script implies. They want or need to complete the task as part of a larger set of tasks that came before, after, and even concurrent with the task they are executing.

Some ways to come up with what happens before and after the sequence:

- Look to the user role, identity - what things do those people do? What larger task do they regular engage in for which this might be a step?

- Look to product claims, statements of value and ask if this user story is part of one of those claims, and how they might look in a real customer usage.

- Look at other features in the product that supply either the input or the output to the features used in this scenario, and “stitch” them on as a next step.

- Grab user stories you already have and sequence them together, carrying all the data and state from one to the next.

- If the user story says the user made a choice in terms of data, or actions, pick something different than the story says and proceed from there either same as story, or changing every few steps

There are a lot of ways to make the story different or longer. It almost always pays off in something the team never anticipated. Most of the team energy has been focused on the stories they wrote down already because those are what they are being evaluated on, what they are checking as they ship.

For example: In my testing session, I extrapolated from building a script to continuing to run that script as the application under development evolves.

How did the testing go?

One of the things I almost always find with scenario testing, or testing of any type, is I find more bugs that are tangential to the specific problem than what the test was targeting. I experienced the same thing here:

- usability issues, such as not being able to choose where recorded test cases are stored, not being able to save captured elements, not being able to edit some properties of recorded elements

- layout and display issues, text layout problems with large objects, resizable UI components where contents don’t follow with the resize, occlusion of objects sitting on top of other objects, layout issues

- data loss, edits in actions which are lost without prompt when clicking around any control that invokes some kind of explicit or implicit navigation in the UI

What about the target problem? That the website it was recording is a bad target for automation, and how modifying that website affects the ContextQA experience? I was expecting to only confront the intrinsic nature of the problem - not necessarily encounter bugs in ContextQA itself. But I did find two issues that suggest either unexpected selection where the script would later select an entirely different entity than recorded, and another where ContextQA was exposing errors that were really faults and exceptions thrown by the underlying libraries.

You can read the report for the specifics. The interesting part is how altering a simple story with just a few changes in terms of data state and “what happens” next is as a way to explore and discover issues in a product.

The moral of the story is…

In this case, the moral of the story is you get a more useful and interesting result if you make the story bigger. Start small, look for the larger context, and ask then look for the next step to take.

What we find when we grow the story are problems and issues and new pieces of information people didn’t anticipate, didn’t know were there. These are the things that fall in between the smaller, shorter, cleaner stories. These are the things that make the story worth telling.