Think Like A Tester And Admit You Dont Think Of Everyting

You need to test like you didn’t think of everything

One of the key principles of CI/CD testing, and unit testing is that you do not add integration and end-to-end tests into the CI/CD pipeline or into the automation. There are plenty of reasons for this, the key ones being that such tests are slower, less predictable, and introduce dependencies and environments which usually are not possible in the build pipeline. To deal with this, you anticipate all the requirements ahead of time, express them in the unit tests as contract expectations via mocks, and test everything in a fast, reliable, controllable, and easy fashion.

It works very well. Until you make an oops. An oops is when you didn’t think of something in the contract requirements. You miss a problem, and a bug manages to go unnoticed by all of your unit tests inside your code and doesn’t show itself until much later. Much later might just be production. That is bad. It is better if much later is before anybody sees it, still under engineering observation and control, so you can fix it. A lot of the time we can automate this testing, sometimes not, but that doesn’t mean we should not do it.

I found an oops. I found it by writing automated integration tests. They are less convenient than my unit tests because they come with a mess of database management and cleanup, and I cannot run them easily as part of any pipeline actions. But they still found my oops. And the tricky part about this oops is it is not the kind that is so easily anticipated by mocking out contracts. In hindsight, it is easy, but ahead of time, you tend not to know until you hit it.

We need something other than unit tests to catch something we did not think of.

Integrating with a vector database

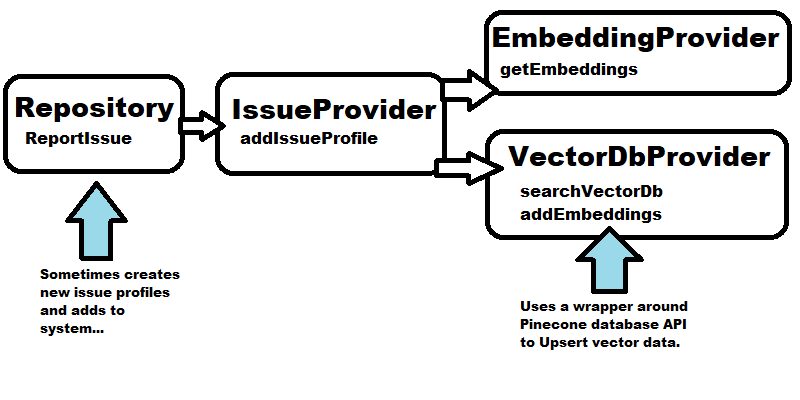

The project I am working on processes issue reports and if they are a new issue stores word embeddings for that issue in a Pinecone vector database. There are three layers, a repository that houses the primary business logic and top level API, an issue provider, which handles the transformation of issue data objects from the underlying storage tier, and the technology specific providers that handle embeddings creation (using OpenAI at the moment, although I am likely to change that to something local for performance reasons) and Pineconce as the vector database query and storage service.

Each of these layers were tested independently. The Repository and IssueProvider

were tested with unit tests. The EmbeddingProvider and IssueDatabase provider

were tested with integration tests (they run against a live version of the

service). The following code is an example test for the IssueProvider’s

addIssueProfile method:

def test_addIssueProfile(self):

passedInEmbeddings = None

passedInProfile = None

embeddings = MockEmbeddingProvider()

def mygetEmbeddings(self, message):

return [0.99,0.98,0.97]

def myaddEmbeddings(self,tenantId,projectId,issueProfileId,embeds):

nonlocal passedInEmbeddings

passedInEmbeddings = embeds

embeddings.getEmbeddings = mygetEmbeddings

embeddings.addEmbeddings = myaddEmbeddings

issuedb = MockIssueDatabase();

def myaddIssueProfile(tenantId, projectId, issueProfile):

nonlocal passedInProfile

passedInProfile = issueProfile

issuedb.addIssueProfile = myaddIssueProfile

issueProvider = SemanticSearchIssueProvider.SemanticSearchIssueProvider(embeddings, issuedb)

profile = IssueProfile("profile1", "test message", Date.min)

issueProvider.addIssueProfile("tenant1", "project1", profile)

self.assertEqual(passedInProfile.IssueProfileId, profile.IssueProfileId, "Fail if profile ids do not match")

self.assertEqual(passedInEmbeddings[0], 0.99, "Fail if the passed in embeddings first entry does not match")

The creation of the IssueProfile input data object is important. The first field is the IssueProfileId field:

profile = IssueProfile("profile1", "test message", Date.min)

The test code for the Pinecone provider behaved similarly, the third argument to addEmbeddings()

corresponding to the IssueProfileId property, and is a string:

...

c.addEmbeddings("t1","p1","i1",embeddings1)

Let’s look upstream to the reportIssue() method inside the Repository class:

def reportIssue(self, tenantId, projectId, issueReport):

s = self.getSimilarIssues(tenantId, projectId, issueReport, 10)

topIssue = None

if(len(s) == 0 or s[0].Similarity < self.SIMILARITY_THRESHOLD):

topIssue = SimilarIssueProfile(uuid.uuid4(), issueReport.Message, issueReport.ReportDate, 1.0)

topIssue.IsNew = True

newIssueProfile = IssueProfile(topIssue.IssueProfileId, topIssue.ExampleMessage, topIssue.firstReportDate);

self.addIssueProfile(tenantId, projectId, newIssueProfile)

else:

topIssue = s[0]

self.addIssueReport(tenantId, projectId, issueReport)

return topIssue

Python programmers might notice a difference between the creation of the IssueProfile object

above and the way the addIssueProfile() method using test input data was created. In the

product code, the IssueProfileId field is created in the follwing line using uuid.uuid4() instead of

a string :

topIssue = SimilarIssueProfile(uuid.uuid4(), issueReport.Message, issueReport.ReportDate, 1.0)

Python is a loosely typed language, so this kind of difference in data type

assignments is easy to do by mistake. The way the product code behaves when it creates

a new IssueProfile object in the reportIssue() code path is different than how

I tested the addIssueProfile() method on the IssueProvider class. Technically, there

is a difference in contract that went by unnoticed. I made a mistake. The mistake

went unnoticed because the units are tested independently of each other. If there are

inconsistent behaviors in the two components and the unit tests are not written

to protect against that specific inconsistency, the problem cannot be

detected by the unit test.

Unit tests isolate test behavior by design. This isolation means they will not tell you when differences in assumed component behavior are a problem.

A unit test cannot detect a problem you didn’t program it to detect. But does it matter? Hmmm???

How I found my oops… integration testing, of course

I wrote an automated integration test for reportIssue() that ties all three levels

together with real instances of the dependent services. The test code

looks like the following:

def test_reportissue_integrated(self):

embedProvider = EmbeddingProvider()

issueDatabse = SqlIssueDatabaseProvider()

issueProvider = SemanticSearchIssueProvider(embedProvider, issueDatabse)

tenantManager = MockTenantManager

repo = repository(tenantManager, issueProvider)

report = IssueReport("integration_report1", "so many things to think about", date.today,"issue1")

profile = repo.reportIssue("testtenant","integrationtesting", report)

...

There is maybe a little bit of irony here, because the code above is

simpler to read than the unit test for addIssueProfile(), but the code under test

is probably five times as complex.

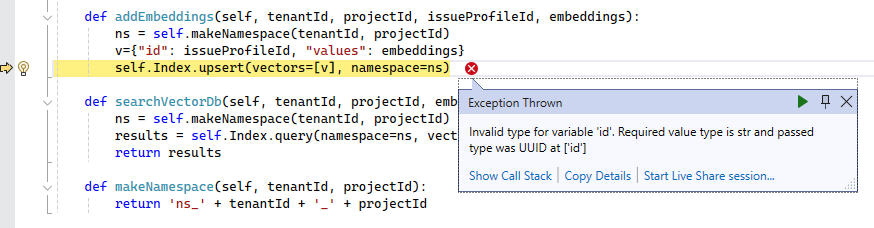

When I ran the test above, I got the following error from the Pinecone service:

Invalid type for variable 'id'. Required value type is str and passed type was UUID at ['id']

Unless you already know that Pinecone requires the id field on an Upsert operation be of

type str you cannot anticipate that this error is going to happen. The error is happening

because two layers up, the reportIssue() method on the Repository class set the IssueProfileId to

a UUID, and the code above uses that value as part of the id field for the Upsert operation.

Integration and end-to-end tests can force out the behavioral inconsistencies between components that unit tests cannot.

Testing that catches oops is like rolling loaded dice

In this case, it was integration testing that caught my oops. I had no idea the attempted

write of the embeddings data to the Pinecone vector database was going to fail. I had

tested the searchVectorDb() and addEmbeddings() methods independently, and confirmed

the data was persited, would round trip when requested later. So how come I was still

able to catch my mistake, even though I didn’t anticipate it?

Because I was allowing myself to lose some control over my test conditions. I was tying the whole system together, and letting it just “do its thing.” I had components behaving out of sync with each other, operating on different assumptions about what had been checked, what expected behaviors were, and I didn’t know it. Combining all the pieces together so those out of sync behaviors could start conflicting with each other made the bug manifest.

I was playing a game of odds and probability instead of a game of control. I was loading the odds in favor of finding an oops, but I didn’t know what I was going to find.

This is almost exactly opposite of unit testing. Unit testing is about defining exactly what will describe a failure by stating which positive conditions, if untrue, will cause the check to fail. For the most part, you have to know ahead of time what those failures will be. This is not 100% true (e.g. product crashes, aborts, and exceptions tend to be unanticipated) but the discipline of writing unit tests is mostly creating reliable, consistent, and well understood checks that will do the same thing every time.

When we go beyond unit testing, we do things that increase the impact of our uncertainty, emphasize the complicated, exaggerate the unknown. My example is a simple case, the basic integration use case, but it is still at least one or two steps away from the clean, 100% understood and controlled testing from the unit tests that preceded it. Truth is the bug wuuld have showed up almost instantly if I stood up the full system and tried out the basic case. Getting there would have been slower, taken longer, and been a collosal waste of effort over something that could have been done easier like I did it here. It really is a simple instance of this “going beyond what you anticipate” situation.

Complement the controlled, anticipated, simple testing from unit tests with more complicated testing approaches that increase the likelihood of observing unanticipated behavior and problems.

These two types of testing are critical and important complementary styles. Used exclusive of each other increases risk and cost. Used together are powerful, effective and efficient.

I like these “first, simplest example of…” cases, because they demonstrate how stark the contrast is as we add complexity and increase our uncertainty. It is a powerful and effective way to make up for our limited perspective earlier on. There are many other, far more complex problems awaiting, and almost all of them are going to have to require creating more complex conditions, testing into more unknowns, and finding rich, deep and surprising gaps in prior analysis.

Tying the whole story together

One of the benefits about writing about testing is I get to use my mistakes, even my stupid ones, as source material for content.

In this case, it was a simple demonstration about how to match your precise and controlled unit tests with larger, more complex integration tests. The one checks the things you know about ahead of time to see if you made a mistake, the second increases the odds that mistakes you did not anticipate, or assumptions you were incorrect about, will be discovered while you are still working on the product, rather than having costs run up on a production system.