Think Like A Tester And Modify The User Stories

Sometimes you need a better story

There is a reference to Peanuts on the wall in this cartoon, as there was a running gag of Snoopy writing on a typewriter while sitting atop his dog house, and so very often his story would start “It was a dark and stormy night…“

User stories are convenient and effective tools for testers, but so often the stories which drive product design and coding are simplified and short. They do very well in a demo, are good for guiding a developer or designer for how the product ought to look and behave, but are almost always too simple and too easy to work well as ways to find problems in a product.

When I am testing, I like to choose and modify user stories based on test questions. I look for things that might take the product into areas that do not work as well, don’t fit the user needs the way we would want.

I employed user stories to test TestRigor, an AI-driven test case generator that uses natural language description of test goals to create the steps for a test case. I have tried prior testing with TestRigor before, but I hadn’t written anything where I targeted the natural language test case generation. I decided to try that today.

A video of the testing session is also available here on my YouTube channel, “Software Testing”.

A note about TestRigor

I am not an employee of TestRigor. I was not asked by them to write this article. I chose it because it has a rich and interesting feature set, and because AI generated test cases are an interesting problem to test.

The story behind the approach

The Personna

A user story often comes with a personna that helps us frame the story, sets down some assumptions of what that person wants, knows, how they do things. For my personna, I intentionally chose a non-technical user, a business analyst at Ford Motor corporation, chartered with creating test cases for their company’s auto-leasing website, Forddrive.com.

I chose a non-technical person because I wanted to focus on part of TestRigor’s goal of helping companies achieve test coverage without having to have trained and skilled programmers write the automation.

The Stories: TestRigor There are two levels of story in this problem, one is the personna as a user of TestRigor, and the other as an employee of Ford Motor. For the first, I am selecting stories that I hope will push TestRigor’s AI case generation features a bit with the following conditions:

- the end user knows none of TestRigor’s jargon or coding language, knows nothing of web-page technical constructs

- the user will describe the test without precise stepwise instructions

- the cases will require multiple steps to properly execute

- the cases will rely on checking states that will emerge only after execution of multiple steps

This is kind of a meta-layer on the stories that is entirely based on my interests in finding issues in TestRigor. In reality, our personna wouldn’t be interested in finding problems with TestRigor at all, so there is a bit of contrivance in my approach, but I also believe the constraints describe very realistic stories that the personna would want to test. Read on to see what I mean.

It helps to build your user stories with a testing purpose that goes beyond the motivation for the stories that were picked by the business.

The Stories: Forddrive.com I chose two basic simple checks based on the existing website at https://www.forddrive.com. Under each I also indicated a set of expections.

- Check that the links to leasing locations point to valid and correct pages

- The script will find the Locations menu and its links

- All the links under the Locations menu will be investigated

- The script will check that the correct city name is on the resulting page

- Check that the Chat help link opens a functioning chat help session, asks for user name, close when confirmed

- The script will find the Chat help link (not on front page, but on Contact Us)

- The script will launch the Chat window

- The script will check that user name is requested

- The script will close the window when done

This check for closing the window is there because I have found from other testing sessions in TestRigor that after the test completes browser window sessions can sometimes stay open with a live connection and active session for a long time. I want to make sure there isn’t a chat window left hanging.

I also added a third story that checks how TestRigor would do constructing checks for behaviors that are going to fail, perhaps where the user was mistaken about a behavior. I modified the Chat story to check for a condition that is not true:

- Check that the Chat help link opens a functioning chat help session and the chat assistant requires membership id before offering support

- Same expectations as prior Chat checks…

- …plus should fail when the assistant does not ask for membership id

I don’t always record expectations for user stories, as the stories themselves tend to describe the expectations. I decided to do it this time because mapping from a natural language description of a problem to a scripted behavior is ambiguous, and expectations might vary quite a lot. It is also easy to become so impressed with AI performance that you forget to compare what it does create against what you wanted.

Adapt your documentation to your testing problem. If a certain format helps you think and test, use it. If it is extra work that slows you down without helping, drop it. It is almost always best to follow your personal preferences.

Telling the stories

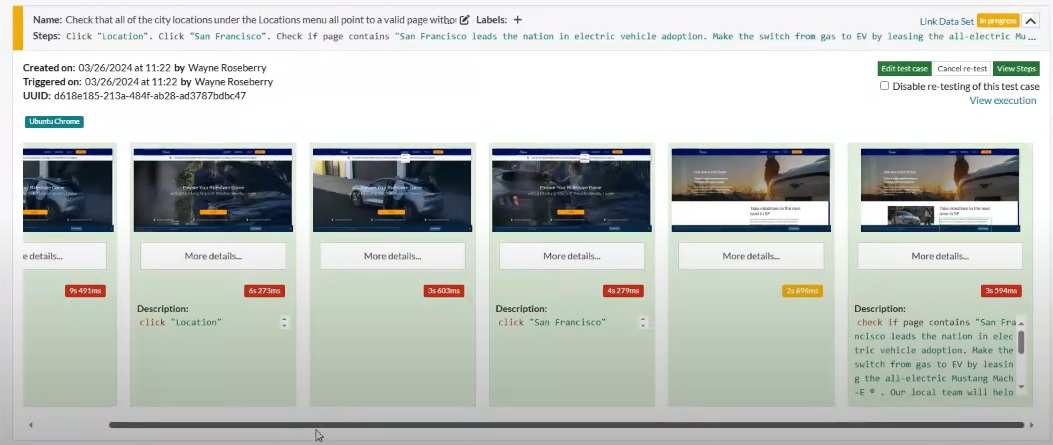

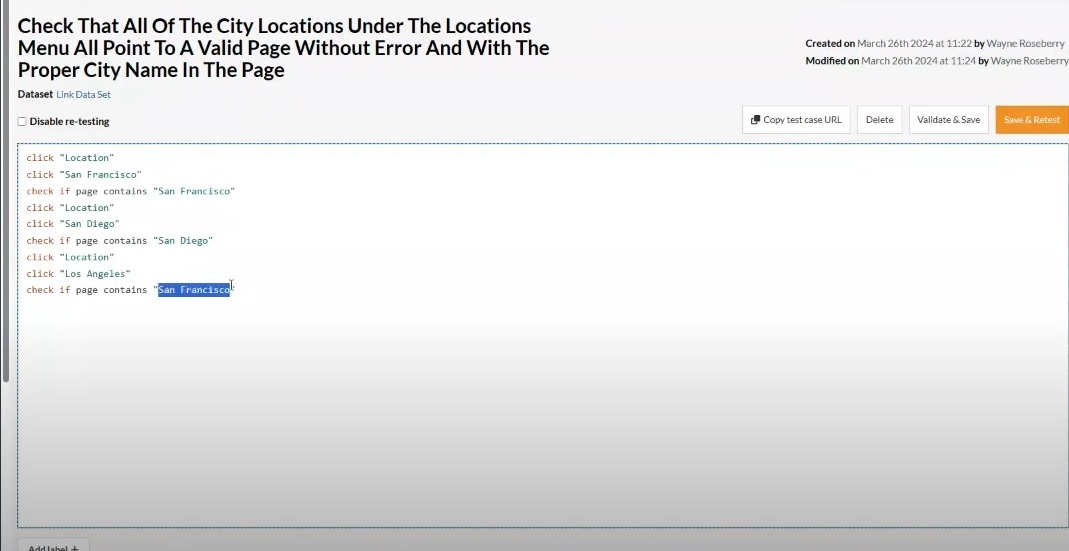

The first user story, TestRigor created a script that immediately found the Locations menu, clicked on “San Francisco”, and then when the page for leasing cars in San Francisco appeared, created a step to check for the contents of the entire first paragraph of content on the page.

There are two issues that come from this run:

- TestRigor did not perform a check for every item on the “Locations” menu as instructed

- The check for the first full paragraph of text on the “San Francisco” page was unnecessary, and probably brittle, because it would fail if any of that content were to change - it should have just checked for “San Francisco” instead

Whether or not these are issues the product team would want to address are a matter for discussion. One of the limitations I have seen with AI generated content is that it tends to perform poorly when generation requires any kind of repeated set of steps. While it did the first step for the first location pretty well, it never tried to repeat the process.

The script, therefore, isn’t what the user wanted. From a user story perspective, we now have new user stories which come of this one:

- A user sees the script isn’t doing what they want, so they decide to fix it to make it do what they want (while staying in their low-technology personna)

- A user makes a mistake on editing the script (e.g. a spelling mistake on name of place to check) and TestRigor should fail because of that mistake

I decided to test these stories as well, because they seemed like a natural extension of what a user would do in these circumstances. Editing steps on a test case in TestRigor is easily done, and at least from my assessment didn’t violate any of the “low-technology personna” limits I had set on myself. All it involved was shortening the text of the check to the city name, and then copy/pasting those same steps twice, changing the click and check commands to match the appropriate cities.

I simulated a user making a mistake by changing the case such that “Los Angeles” was spelled “Los Angles”. TestRigor behaved as per expectations and failed the test case.

Add user stories as you think of them, especially if they make the test more interesting. You are exploring the possible user situation and usage as much as you are exploring the application.

ISSUE: There is another issue with the generated scripts that I did not recognize when recording the video, and only just realized now writing this article. The end user intent was to solve a general problem of checking that location links were valid, but TestRigor created a script for specific links. This means that were any of the links, for example “San Diego”, to be removed at some point, the script would yield a false positive - it would declare failure over something not meant to be a failure.

The second and third user stories, opening a chat help session, yielded more issues. TestRigor’s starting behavior was impressive, because it found and clicked the Chat link under the Contact Us page without being told that is where the link was. It had to navigate to the Contact Us page first, on its own. After that, there were several issues, and violations of expecations I had not anticpated:

- It tried to close the window before checking the assistant content was correct

- It used the entire paragraph from the assistant to check if what was there was expected instead of just looking to see if it asked for user name

- The “click Close” attempt was executed when there wasn’t an obvious “Close” control on the page, leading to an entire question of how the end user knows what TestRigor was even trying to click and how it was going to try to do it

- It added steps, such as typing questions, inventing names for itself and sent it when the chat assistant asked for it, invented a problem “Hello, I need help with my account”, injected checks for content with current time in them (e.g. “Check if page contains ‘11:44 am’”), asked for help with the membership id instead of checking if the assistant asked for it (e.g. it sent “I for my membership id and I need help with my account.”).

- Behaved in a way such that the chat assistant was beginning to direct the test client to a live chat agent

- Never did check whether the assistant asked for membership id, and consequently declared the test a pass

Most of the failures you observe during user story testing are likely to be something you did not anticipate. Pay attention to as much as possible, do not lock yourself in to a rigid set of requirements or become numb to odd behavior.

It is fair to say that TestRigor went completely rogue on the last user story. The behavior that is most concerning is the way a simple check to see if a chat assistance session was functioning correctly almost turned into a full on conversation with a human support engineer. This is the kind of behavior we want to avoid, and don’t want to accidentally make it happen because we cannot predict the behavior of our autoamted agents.

I have actually done a lot of testing using autonamous, AI-driven agents, and this problem of the agents stumbling on behaviors you do not want them to hit happens quite easily and can be difficult to suppress.

Taking user stories one or two steps deeper, especially down failure paths, is an effective way to raise issues that are at least interesting and useful for the product team to know about.

The moral of the story

I started off by saying how I like using user stories to guide testing, so that is clear. In this article, I conveyed some approaches to doing so that I find work very well.

- User your tester’s understanding of the application and what might raise problems to create a criteria for the kinds of user story you want to use. Select and modify the stories to fit this criteria.

- Keep a sense of freedom around the story. You will think of new stories, you will change the story you are testing. Follow that instinct.

- Even if the stories do not demonstrate bugs or failures, it is useful for you and the product team to know what happened when you did try the story.

- Stick with the user personna. Try to pretend you are them, and try not to step out of their personna when looking for workarounds or how they would deal with a problem.

With those guidelines in hand, you should also be ready to try some testing and tell a story.