Different Approaches To Test Cases

Different ways of representing test cases

=================================

At some point testers need to write down what testing they intend to do, or account for what testing they have done. The common convention to describe a specific performance of a test in terms of the conditions, the steps taken, the checks performed, is with the term “test case.” There is a lot of historical baggage around that term, especially with regard to formally scripted testing narratives, which I believe gets in the way of understanding what a test case really is and what we mean when we use the term. I cover my definition of test case in another article, What happens in the case when you are testing.

In this article, I describe different forms for describing test cases. I especially focus on how those forms affect cost and efficiency, but also describe when they may or may not each be useful.

The ways vary largely on detail and cost to maintain

The following list of different ways of representing test cases go from high detail/high cost to low detail/low cost.

- Fully-described test cases in list form

- Titles only test cases with shared steps

- Grouped test cases with shared steps

- Grouped test cases with implied steps

- Test case ideas and themes

Over the years, I progressed from high detail and high cost lists of test cases, steps fully described, to low detail and low cost groupings of test case ideas, relying on the knowledge and skill of the tester to understand the steps without me writing them down. I also sometimes cover test case ideas and themes and know a lot of testers that get a lot done with that low level of detail.

I describe here how I view these different representations. One may find a reason to prefer or need each, although I have also found that sometimes people represent their test cases in a way that is not suitable for the problem they are working on or situation they find themselves in.

Fully-described test cases in list form.

Test cases fully described in lists represent the most formal, detailed format for test cases. Every single instance of something to test where conditions or inputs are different is described as its own test case with its own steps. Steps are detailed, permitting little to no variation.

Title: Do thing to the stuff with value = “John Smith”

- open app

- click on Page1 from top ribbon

- click “Add thing” button

- first name, enter “John”, last name, enter “Smith”

- click OK

EXPECTED List of things has one new row with First Name == “John”, Last Name == “Smith”

Title: Do thing to the stuff with blank last name

- open app

- click on Page1 from top ribbon

- click “Add thing” button

- first name, enter “John”, last name leave blank

- click OK

EXPECTED List of things has one new row with First Name == “John”, Last Name is blank

The usual goal for this approach is to have a set of instructions which may be followed by someone (or something) that knows nothing of how the product works. The cases could be given to anyone and that person would know how the case is executed. This approach is used when cases are passed around a group of people who do not know the product well, when some other entity has demanded such a format for review. Such test cases are almost always stored in a formal test case management system of some sort as a separate entry per case.

This approach is difficult to maintain and tedious to review. It is difficult to understand a larger context when reading the case details. It is difficult to visualize what is changing from case to case. Small changes in the product behavior invalidate large collections of steps, demanding suite maintenance over time to keep the cases relevant and up to date. The approach sometimes has the effect of limiting the imagination of testers who follow steps and procedures blindly without looking beyond the recorded actions and expectations to explore new possibilities, record unanticipated problems.

Reporting

Reporting on such an approach tends to be tables of cases with pass and fail indicators next to them. Overall report tends to be numbers and percentages of cases passed or failed.

Titles only test cases with shared steps:

Titles only test cases maintain the same one test case per variation pattern as fully-described test cases, but the steps for the test cases are shared centrally and authored in such a way that the steps adapt to the changes in test conditions and inputs. Actual steps are stored in separate collateral from the test case itself.

Title: Do thing with stuff with First Name = “John”, Last Name = “Smith”

- see “Do thing to the stuff with different values” steps in test plan

Title: Do thing with stuff with First Name = “John”, Last Name =

- see “Do thing to the stuff with different values” steps in test plan

In test plan: Title: Do thing to the stuff with different values

- open app

- click on Page1 from top ribbon

- click “Add thing” button

- enter value for fields specified in case

- click OK

EXPECTED List of things has one new row with columns corresponding to test case having matching values

The goal of this approach is to preserve the same degree of ability to have someone that does not know the product execute the cases, as well as case by case accountability, but with reduced document maintenance cost. It means that along with cases stored in a case manager, the people running or reviewing the cases will need access to the test plan document somewhere.

There is still a high cost of case creation and maintenance for the planning documentation, and even the test cases themselves. Each case needs entry in the case management system, even if full step articulation has been removed. The original steps need to be written, and need to be changed as the product changes.

Reviewing testing ideas and cases with shared steps is far easier than fully-described lists. The reason is because the steps are typically shared across test problems with lots of similarity, designed to explore behavior and risk around specific types of problems. This kind of grouping helps people understand the test approach better. Rather than looking at hundreds or thousands of cases one at a time, they can focus on the purpose and strategy behind those cases, why they exist.

Sometimes this approach is used in conjunction with less expensive approaches when the test procedure steps are not obvious, or must be exceptionally precise. That sometimes happens when a test problem is very difficult to understand, even for an expert.

Reporting

Reporting for titles-only test cases is usually identical for fully-described test cases.

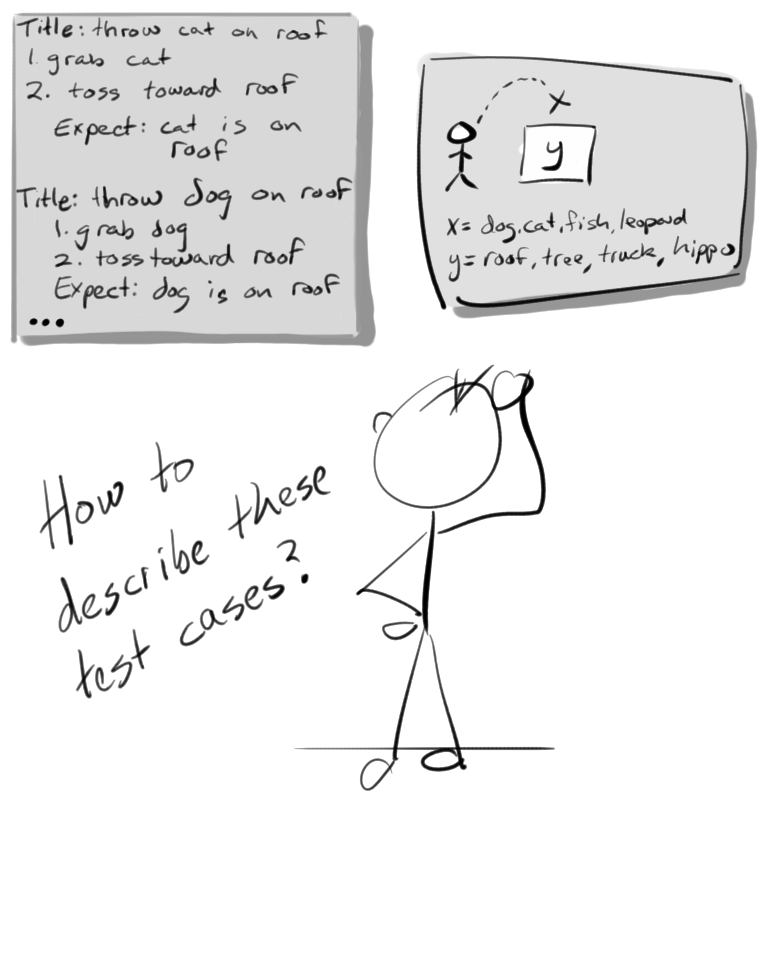

Grouped test cases with shared steps

Grouped test cases make one entry in whatever list or case management system for many cases at once, and refer back to a test plan for a description of how to expand the group into individual cases. The expansion of entry to cases could be 10x, 100x, 1000x or more.

Title: Do things with stuff and different input values see “Do things to the stuff with different values” in test plan for full set of cases.

In test plan: Title: Do thing to the stuff with different values

- open app

- click on Page1 from top ribbon

- click “Add thing” button

- enter value for fields specified in case

- click OK

EXPECTED List of things has one new row with columns corresponding to test case having matching values

Cases:

First Name, Last Name over values of [“user1”, empty, “ “

The goal of grouped cases is to preserve the recording of steps for re-use while reducing the cost of authoring and maintenance of the test cases. There is still an authoring and maintenance cost for the original test plan to capture steps and keep them current. This approach sacrifices per test case accountability in test case tracking reports for sake of cost and speed.

All other aspects of grouped test cases are similar to regular test cases with shared steps. Similar advantages, with the difference being a reduction in the number of cases actually entered into tracking mechanisms. A lot of testers and test teams find grouped test cases a comfortable compromise even when they prefer having steps fully articulated.

Reporting

Reporting for grouped test cases will typically drop the pass and fail considerations, as the group hides the per case details. Instead, coverage is described based on the topic the group suggests, with indications of whether the group is covered yet and whether problems were found covering that group. It is usually easier to understand coverage with grouped cases.

Grouped test cases with implied steps

Many testers drop steps from their description of test cases, relying on the person performing the test (who is usually the same person as the author) to learn and know the product. The purpose of the group is described in the test plan with enough information to visualize what the test would be. The cases are described in a way that is short and fast to read and easy to visualize the expansion. If a tracking system is used, the group name is usually the title of the test case entry.

Title: Do things to the stuff with different values Apply the following set of input values to adding a new thing to the stuff list, and check if the list view shows the new item with the values specified.

Cases:

First Name, Last Name over values of [“user1”, empty, “ “

Grouping cases with implied steps offers much faster time to creating the testing collateral and describing the test methodology. Time that would have been spent on rote recording of steps is all transferred to thinking, analysis, and creativity. Maintenance costs are reduced sharply to a minimum such that change is only needed if the fundamental problem changes or if critical aspects of how things are done, checked, or analyzed must change. The approach relies on the tester deeply understanding the product they are testing, which can be utilized as a way of further reducing maintenance costs, assuming the tester will “keep up” with current status. Many testers find the balance of speed, reduced cost, and recording thoughts sufficient to describe a plan suitable for covering their features.

Implied steps in test cases does mean tradeoff to testers unfamiliar with the feature is not going to work without additional support in the form of training, guiding materials, or longer onboarding time for the new testers to learn the feature. It adapts poorly in “handoff the testing” situations, particularly outsourcing to vendors outside the team. It is also the case that vendors who want to provide concrete evidence for time spent working on test suites, running passes, will prefer fully articulated suites of test cases to directly reflect billable activity.

Reporting

Reporting on grouped cases with implied steps is similar to reporting on grouped cases in general.

Test case ideas and themes

An even lower level of granularity describes testing by ideas and themes for exploration rather than articulating exact cases. Some set of aspects of the product or system will be modelled in relationship to test conditions, problems, or risk areas. Such ways of modelling the test ideas provides more of a broad coverage map, and requires more work and imagination, and frequently exploration, to express the combination of ideas as individual cases. The specific test cases may not have even been imagined yet in this approach, they are sometimes emergent from exploration during testing.

Title: Different values for thing across input spaces Explore affect of different data across the following features allow user to view or edit Thing in some way

- new thing control

- stuff list

- select thing action menu

- display thing on notifications

- assign thing control

Cases: Each of the fields on the Thing class across values for inputs reflecting valid, special characters, double byte, international character sets, HTML characters, SQL injection possibilities, invalid inputs

This approach is popular among testers who lean heavily on non-scripted exploration of the product. Maintenance cost of the test plan is probably lowest possible of all the approaches. Planning time is dedicated to imagining what types of problems the tester is interested in relative to which aspects of the product or system. Specific test conditions or inputs are frequently described somewhere in supporting material - usually lists, data sets and such - but the tester also frequently modifies test conditions during execution, something testers exploit to enrich coverag and discover behaviors unanticipated during coding, design, and planning.

This approach adapts well even if the tester is new to a product. They may have enough knowlege to craft the analysis above, but they may not necessarily know how every aspect of the product works, they just know the ideas they waynt to explore. Because of this, the approach relies heavily on the ability of the tester to create, adapt, improvise, analyze, and explore a system, reporting problems found, even when they are new to and unfamiliar with that system. Sometimes the output of a “completely new, know nothing…” testing survey session is a plan describing test case ideas and themes.

This approach works equally well when the tester has deep famiarity and expertise with the system. They can rely on what they know already to fill in the details for the broad strokes describing the domain the cases will cover.

This approach is poorly suited for handoff to any group of testers that do not demonstrate strong exploratory approaches. When working with vendors, check their technique and approach. If they describe their coverage in terms of ensuring or verifying requirements are met, then this approach is not going to work for them.

Reporting

Reporting for test case ideas and themes is similar as to grouped cases, although there is a tendency for even more clustering and abstract summarizing. The reporting tends to be simpler to read, shorter. There are fewer numbers and more “temperature map” type results, showing which areas of exploration are done, which in progress, which not done at all, and where the problems came up. It tends to be easier to describe big picture with test case ideas and themes.

Conclusion, I guess…

The key takeaway I want for anybody is to recognize that when we describe test cases we are trying to solve a problem. We are not trying to adhere to a ritualized set of rules or standards for how to record our activities. We should take cost, effort, value, usefulness of what we do and how we do it into account. All of the ways of approaching test case description in this article are useful in some way, but they also all have times when they will not fit the situation well. The most common tradeoff involves time, cost, and expertise required in the approach.

And I guess I cannot say that much without saying the above is not a religious canon. If you find or invent a way of describing your testing, cases or whatever, and if it works for your situation then use it.