Digging Through Data Is Testing

Sometimes you test without executing a single test

This week I decided to investigate the logs on one of our production systems. I did not have an exact intent in mind. I wanted to see what kinds of things I could learn from the logs. I am new to most of the technology we use to build the services, so it was also a way for me to get more comfortable with the infrastructure, tools, and entire tech stack.

Getting at the data

The service runs on Google Cloud Platform. I used Log Explorer to look at the production logs. I found one of the types of log entries I was able to find were API calls to one of our backend services. I wondered if I could use this query to build a model of end user behavior and then compare it to our testing coverage.

The API is REST based, and the calls to this service take the following form

in the jsonPayload.message part of the log entry (I am obfuscating some details):

SECURED PATCH /v2/ourservicename/ABCD/command1

The command1 part at the end corresponds to whatever action is being taken,

while the ABCD is an identifier for the item being acted on by the API call. There

is also a time of the event in UTC form in the resource.timestamp field. I realized

I could build a lifetime of the item processing by splitting the URL apart, extracting

the identifier and command, and then sorting by identifier and timezone.

Crunching and reshaping the data

I exported the logs to CSV format and opened it in Excel. I chose Insert/Table to make things like referencing columns and autofill available (I almost always work from tables in Excel). Now came some Excel formula writing.

Side comment on Excel: editing formulas is still tedious and awkward and error prone. I like using Excel a great deal, but the formula editing experience for decades has been all about trying to follow what one is typing into a tiny little window, attempting to reference items by clicking on them even when the UI is covering those items with various hints, popups and controls, and when slight little mistakes cause Excel to loudly and obtrusively take focus away from what you are ever so delicately trying to do to give you a modal error pop-up saying the formula has an error in it. For crying out loud, this app is over thirty years old, is the best spreadsheet on the market, but it still has a dreadfull formula editing experience.

I extracted both the identifier and commands into their own columns by using INDEX(TEXTSPLIT(...)).

(One of the greatest commands added to Excel not too long ago is TEXTSPLIT.) I converted the resources.timezone

field into a date and time format that Excel could handle using another formula (the T in the middle of a UTC formatted

time doesn’t work for Excel). Next came one of my favorite features in Excel,

pivot tables.

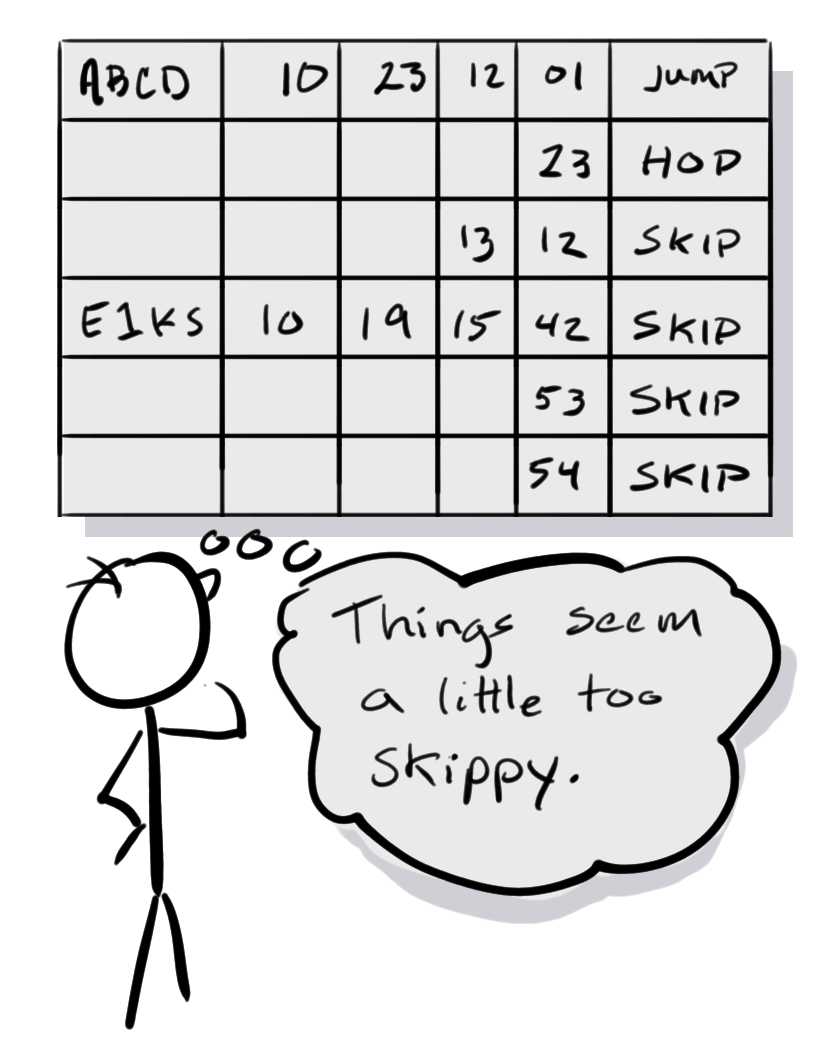

Using pivot tables, I set up the row labels in this order: identifier, datetime, command. Excel automatically splits a date formatted column into separate Year, Month, Day, Hour, Minute, Second fields. They Year column was the same across all my data, so I removed it for readability. This resulted in a table which looked similar to the following:

| Identifier | Month | Day | Hour | Minute | Second | Command |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABCD | 10 | 23 | 15 | 37 | 41 | command1 |

| 15 | 42 | 13 | command2 | |||

| 10 | 24 | 18 | 12 | 26 | command3 | |

| EDJT | 09 | 30 | 16 | 52 | 19 | command4 |

| X1RF | 10 | 12 | 19 | 18 | 37 | command3 |

| 18 | 53 | command3 | ||||

| 19 | 11 | command3 | ||||

| 19 | 39 | command3 | ||||

| M2UF | 10 | 22 | 17 | 30 | 09 | command5 |

There were hundreds of rows such as above in the table. I noticed some patterns right away:

- The logs afforded a 30 day window, so some start of sequence actions on the identified items were in mid-lifespan, whatever previous action happened prior to the log window.

- It was also clear that some actions would happen close together, within seconds of each other, while others would take longer - maybe days between one step to the next.

- Some commands would repeat several times before moving to a different command.

The end users of this system consist of two groups of people, customers of the service, and sales operation staff who interact with the customer. Some of the actions in the system indicate steps that require something happening in the real world that physically take time. I was still getting familiar with which commands corresponded to which actions different end users might take, so I wasn’t sure if these time gaps were expected or unusual, but it was interesting to see the patterns.

I showed the data to my testers.

My testers hold a mid-day daily meeting for drop-in catch up, question asking, and information sharing discussions. I dropped in and showed them the spreadsheet, explained how I got the data. This was an enjoyable and enlightening discussion.

Some of the actions should never be close together in time.

They represent something where an operator takes an action in the UI, the end user has to do something in the real world, and when they are done the operator takes the next action. Expected time between is more likely to be hours, even a day or two. We were seeing entries between steps that were seconds.

The interpretation the testers took of such events were that it was very likely there had been some state problems where the application was having trouble, and the operator was trying to address it after the fact. The other idea was that maybe there was some kind of delay between the UI where the operator performs the operation and the actual call to the service API. In either case, they took it as an indication of some kind of problem state.

Repeated actions and sequences that didn’t make sense

Some of the commands should always go from something like command3 -> command4. Instead, we

were seeing things like command3 -> command3, or command3 -> command5. Further, in some instances

a command would repeat more than one time - four or five times. In most of these cases, the

tester interpretation was that something was going wrong on the system preventing the expected

transition of state, and the operator was repeatedly trying the operation to make it work.

Repeated actions that made sense after we thought about them

There was one command that corresponded to a customer returns item use case which would repeat,

and at first appearance that made no sense. How could a customer return the same thing twice?

But then one of the testers pointed out that the operators of the system use the same UI (and thus API) action for customer returns item

as they use for customer swaps item for a different one. The repeated of the action was indicative of

a return of the second item at some point after the swap.

My thought on this one was maybe we ought to talk to the product group about treating swap and return as different events in the system. In the current state, we could not, from the data, distinguish between repetition because of a problem, or because of a normal use case.

Some of the timing of events seem to correspond to incidences on the service

The testers and developers keep a close eye on production incidents in anticipation of having to fix and test something in response. We didn’t formally match each of these API calls to when the incidents were reported, but there had been enough incidences about various operations not processing where a developer had applied some mitigation and asked operators to try again to explain some of what we were seeing in the log data.

My testers clarified for me which commands correspond to which actions

Out of about seven or eight commands collected in my analysis, one of them corresponded to actions a customer would do on their own, while all the rest represented actions a sales operator would take in response to customer actions or while interacting with a customer. They also helped me understand which actions make sense coming close together in time because a person is performing a sequence of operations at a machine, and which make sense with larger time in between because the next step is waiting for something to take place in the physical world.

This motivated some thoughts about our testing

The extraction exercise and observations from my testers gave me several ideas about testing and the product/service quality.

- A lot of the unexpected behavior seemed to be about people responding to data state, which suggests we ought to test more there

- Order of operations falls often outside the anticipated “happy path” scenarios, so we ought to exercise those paths more

- Extracting identifiers and other meaningful information from mid-URL is an awkward way to process data, see if we can add the information as specific fields on the log entry

- It may be worth building tools to store information longer the 30 day log window to permit longer trend analysis

- It may be worth investing in more visualizations and analysis tools

- It may be a good idea to correlate backend activity to incident reporting activity

- Excel is handy for off-the-cuff data analysis, but tedious if you expect to do something a lot, so maybe consider writing some code to do the same thing faster

- Some of the use cases are ambiguous in the API data (e.g. “swap” versus “return”) and might warrant some design changes

As I said, sometimes testing isn’t about executing tests

Testing is the act of learning about a product via exploration and observation for the sake of understanding risk. We often imagine that as a kind of experiment where the tester tries something, makes an observation, considers if anything they observed seems wrong or unusual, repeats that across a set of things they want to try, and reports their findings in the end. We usually think of each little experiment, what some call a test case, as the whole of testing.

Another way of testing is to explore information coming out of a system. You do not need to evoke action in the system, or change a test condition. You can observe the behavior of the system and look for what actions are already happening, what conditions already exist. This is a form of signals based testing, but without applying a workload to generate the signal. You may or may not discover bugs in this process. You might only realize or understand a test condition, behavior, action, or coverage idea you had not considered before. You might recognize risk that has not been investigated. Whatever you find, you are still engaging in a productive form of testing when you go digging through the data.