Maximize Testing By Changing The Development Schedule

Sometimes testers do need to change the development schedule

I am used to developers and testers mostly owning their own work without too much mixing in between. Creating the product and testing the product are two different activities, each owns the responsibility for their own work. I am not opposed to people mixing up what they do, taking on a different role or responsibility at some point in time, but the way I talk about it, I like to keep the ideas and words distinct. Development is one thing, testing is another.

There are some blurry parts. Some of that blurring becomes more apparent when trying to manage product delivery schedules that are quicker to respond to change.

An example of such blurring is the development schedule. On larger milestone projects, developers typically entirely own the schedule of what they write and when. Testing is typically entirely reactive to that schedule - adjusting to whatever the developer does (whether by intent or accident). That clean line blurs more as maximizing testing capability becomes more and more important to responsive product delivery. The tester is at an advantage if they work together with the developer to plan and design the development schedule.

Here is an example from the trenches

I am using an example which happened one time at work. I am going to replace some details with generic concepts, but the ideas are still the same.

How the work was going to be done…

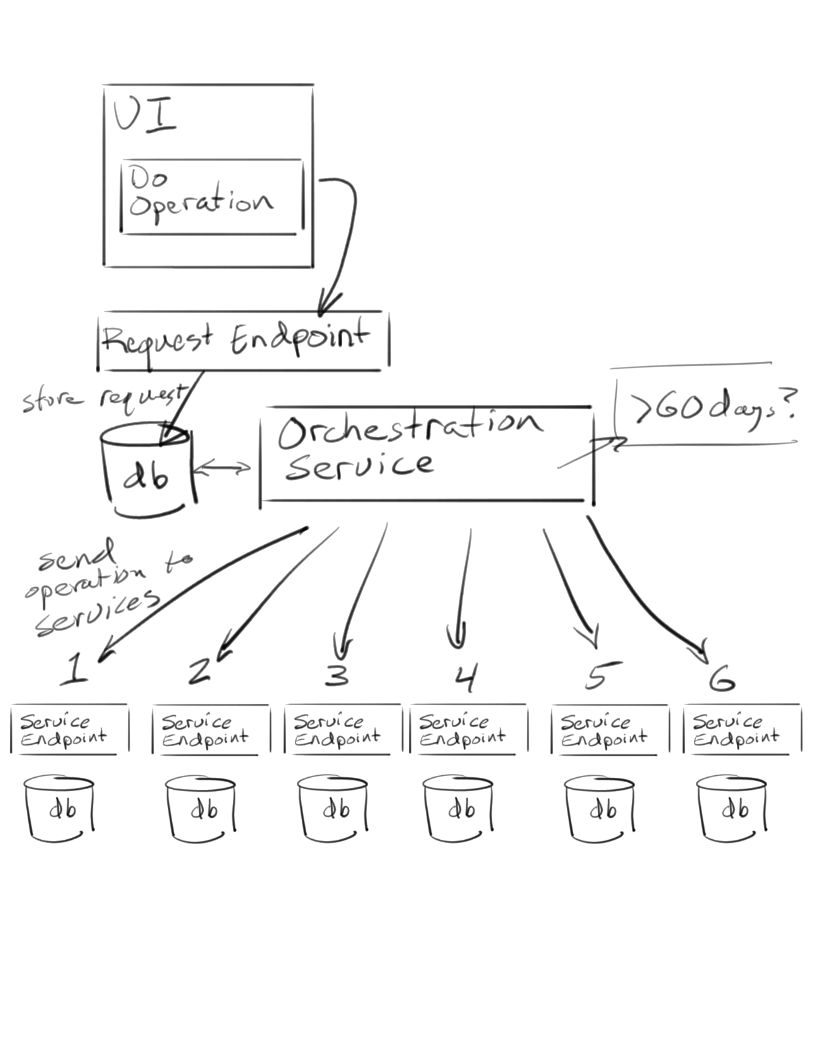

There was an upcoming feature which required an operation to cascade across several services. Data important to the end user is stored in multiple repositories behind multiple API endpoints. The entire use case was incomplete if it did not succeed in all services, and was designed to stop if any of the services indicated failure executing the operation. Further, end users had up to 60 days to contest and reverse the action, but likewise the operation had to be verifiably complete by 60 days if the end user ever requested.

The general design was this:

- each service implements the operation at their API endpoint and is responsible for executing it in their respective repositories

- the request for the operation is stored inside a database with the date of request stamped on the row

- an orchestration service looks in the database for any operations at the 60+ day threshold and calls each service API in order, and updates status on the request in the database based on it either being complete, or having hit a failure mid-point

- somewhere in the end user UI is the ability to invoke the operation, which stores the request in the database as per above

- operations UI exposes the ability for the end user to revoke the operation should they request it

The service was originally designed as multiple stories, with the user interface implemeneted first along with the orchestration component, and then the service API endpoint implementation following after. The idea was that end users could begin requesting the operation, which would sit in the database ready to be executed 60 days later. Developer estimates were such that completing the remaining endpoints would fit easily within the 60 day window.

Testing was assumed to work the way the team was used to. Each story would involve about 10 days or so of development work, followed by a deployment to staging where testing would begin a pass. At the end of the pass, testing would indicate if things looked good and everything would deploy.

How we changed the schedule

I, and the other leaders on the team, have been working to break the team of these large coding and testing block schedules. This is how we asked the developers and testers working together to change the plan.

- Enable the UI last

- Break every component, the service endpoints and the orchestration, and the UI, into their own deployable change

- Implement the service endpoints and orchestration component in whatever order works

- Hide ability to request the the operation behind a feature flag, waiting for testing of the end to end integration to drive the decision to flip it

The reason for the above change in plan:

- it gets rid of the race against a 60 day clock

Even though the development estimates fit easily in the 60 day window, we did not want the team to panic anticipating the deadline. My experience is that things go wrong often enough that estimates are untrustworthy. People panic on a deadline and make poor decisions about what to change, fix, test, skip, or ignore based the pressure of making a date instead of making the right decision for the customer and the business.

- every component goes in when the testing on that component feels right

Each piece, the UI, orchestration, and every service endpoint, has some body of testing to do against it. We can decide for each one what that is, and whether we believe it needs more or less. The information we get about each one as we test informs the decision about whether or not to deploy that piece.

- we are looking at small bits of change instead of everything all at once

When the changes are delivered in a big block, representing many days of development work, the testing problem is far larger. The complexity of tracking down bugs, being blocked behind issues in services, understanding what is happening, achieving coverage is much more difficult, and much more expensive. Smaller components are much easier to test and have a smaller risk surface than everything deployed all at once.

By deploying small changes, we also can monitor the production signal to look for problems we might have missed with the change. This allows us to address the problems in tandem with working on the changes that come after. It also sets more granular tracking of when certain problems appeared, because we can order after which deployment we saw something come up.

- we ease the penalty of taking longer

When a large story has been under development for multiple weeks already, almost always taking longer than the original estimate, pressure starts to build to make a date. Testing time is almost always compressed in this model because realistically you are probably looking at the 3-4 weeks of total story time needing something like another week to account for extra testing to deal with problems that accumulated in the development phase. It is very difficult to accept a delay of that sort when the entire story has taken 3-4 weeks already.

By contrast, if something was estimated to take 1-2 days of dev/testing together, and coming into day 2 it is clear testing and fixing is likely to take another 1-2 days, the usual response is “do whatever it takes to get it right.” It is a strange psychology, because in the end “do it right” likely adds up to the same amount of time overall, but people have an easier time accepting, managing, and understanding that decision in small steps.

Think about this problem like a tester and a developer working together

The more common and traditional approach to testing and development sees the two as very distinct activities and very distinct roles. The developer doesn’t tell the tester how to test, and the tester doesn’t tell the tester how to code. Creation and observation are two different activities with two different skill sets which we often separate for very good reasons.

But sometimes it is better if you mix them up.

Maximize observation, maximize testing

Testers and developers have a shared goal to maximize testing opportunity and capability as much as they can. For sake of argument, let’s keep building the product cleanly in the developer’s responsibilities, and testing the product cleanly in the tester’s responsibilities (for sake of argument only, in reality I advocate something much more nuanced and complex). Even with such a distinct separation of responsibilities, both parties have a critical interest in maximizing testing opportunity and capability. The tester wants to provide the most useful and valuable testing they can to the developer, and the developer wants the information from that testing to guide them in fixing the product where they must.

Aw heck, let’s pull the product manager in as well. They want the same thing - they want to make good decisions about what features are deploying when. They are frequently involved heavily in schedule decisions, so they gain to benefit from maximizing testing opportunity and capability.

Here are the guideline ideas covered in the story above:

- break apart large changes into smaller components that can be tested and deployed independently

- 1-2 days of coding is usually easier to cover in testing

- 5+ days is difficult to test quickly or reliably

- “ripple effect” changes are deceptive, small coding is not always small testing

- some changes are small enough risk to rely almost entirely on unit and contract tests

- 1-2 days of testing for small components is probably comfortable

- 5+ days of testing is a “smell” that suggests maybe the change under test is itself too large, or at least a sign that the risk needs to re-order to put it later

- use deployment capabilities to mitigate risk

- feature flags

- staged rollouts

- blue/green deployments, rollback

- monitoring and fast response to problems

- have a plan for knowing if anything went wrong

- create a monitoring story for every change

- for checking value of a change, create ways to measure engagement, change in behavior

- order the schedule of deployment and capability enablement to defer risk later

- integration is riskier, usually better done last

- UI is usually riskier because it exposes functionality end users

- order the schedule to permit longer, deeper testing to accumulate across the smaller changes

- end-to-end scenario tests usually take longer and tie everything together

- large data operations: migration, transformation, data flow through integrated systems

- load, reliability, performance, scalability - anything which requires hours of workloads and deep data analysis

- remove artificial time limits and barriers and instead let natural decision making based on testing and information guide the “when”

Following such guidelines, the developer needs to understand what the tester intends to do, and the tester needs to understand what the developer intends to do. The two cannot work independently to create the schedule above - there can be no “over the wall.” The tester can say “if you do make this 5 day task into two tasks deployed independently, then we can get each of them covered easily with their own testing, and then push the integration out to after that which can take a little bit longer”, and the developer might say back “I believe I can make it even better if we split that 5 day task into three deployments, the first of which I can probably cover entirely with unit and contract testing, and meanwhile you get the sytem testing ready for the 2nd set of changes and forward…”