Invaluable Testers Create Their Own Test Ideas

You Need to Add Value to be Invaluable

I came across (yet another) post from someone on LinkedIn who said that independent testers create inefficiency because information has to pass from the developer to the tester. The suggestion was that everything would be more efficient, better, faster, if the developer had done their own testing. Information handoff removed, inefficiency reduced.

If all that the tester does is repeat some use case or scenario or set of steps they were told by a developer or product manager, then what this person said is correct. All the tester is doing is something the developer should have done already as part of responsible development.

A tester should do different and more than the developer, product manager, and likely nobody else on the team would. Transfer of information is only inefficient when there is no transformation of value; if it goes from developer to tester and nothing changes. The tester should use the story, scenario, or any other piece of information and change it to something different that serves as a more effective way to explore and learn about product risk.

In more familiar company, I sometimes say it more impolitely:

F— the happy path.

Forget the happy path

Now that I have chosen a more family friendly phrase to label my approach, let’s think for a moment what we mean. What should the tester do? It is one thing to say “think like a tester and change up the inputs”, but what does that really mean? The truth is it means a lot of things, but in particular, I like to think of it this way.

Imagine things you can try or explore which increase the probability of finding something that puts the product value at risk.

Given that idea, let’s think about taking the use cases as described by the product manager or the developer. Typically, that use case, scenario, or story, as written:

- has been discussed in-depth by everyone

- is one of the easiest things to think of

- the developer very intentionally tried to make that exact thing work

- was very likely already tested by the developer

- has a decent probability of being in the product manager’s demo

- is going to get noticed very quickly by a lot of people if something is wrong

Given all of that, the probability that the scenario or use case, as written is broken is low. And even if it is broken, the probability you will realize it is broken while looking at related cases which go through the same functional path is high.

Executing a scenario or use case exactly as written in the requirements consumes time testing for a low risk failure probability. Your chances of finding something broken are diminished and you are more likely to find important bugs doing different tests.

We may be overwhelmed, confused, or unsure of what to do at this point. There are so many possibilities. What should we try? How do we pick? What sorts of things can we do?

Just change it.

That might seem dismissive, or cavalier, but it is a surprisingly effective way to go. Change the scenario in some way, any way, and see what happens. The number of bugs discovered by choosing random small changes is surprising. Small changes also frequently make you think of more small changes, which leads to discovering more bugs.

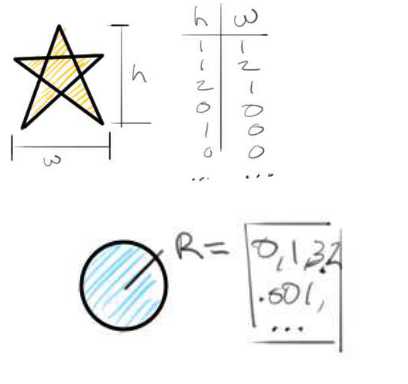

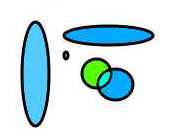

There are some change patterns we use frequently, and a small sample of them are captured in my cartoon above.

A few ways to change the scenarios and stories

There are lots of ways testers change scenarios, use cases, and stories. The list that follows is not an official collection, and it is by far not exhaustive. It is mostly constrained by how many shapes and ideas I could reasonably fit in a 8.5x11 comic page. It is meant as an example of ways of coming up with new ideas that might help. It is a hint, a nudge, for a person to come up with even more.

In my cartoon, I used geometric shapes to symbolically represent the use cases, or data inputs. I wanted to abstractly express the notion of some kind of example without having to reference a specific kind of technology of application. This is because the examples I give below of ways to change the information one is given are generic in the abstract. You can apply these ideas to steps in a UI, input formation, database structures, environment configurations, argument input values, or any number of things. The examples below are all about geometric objects, but that is only because they are so familiar.

Going through some parts of the cartoon, here are how one might interpret each of them.

Make a model of the object and its attributes

I almost always make some model of what I have been given. What are its parts, what relationships do those parts have to each other? What values can we ascribe to those parts? Can values for those parts combine to make interesting test conditions?

Frequently we come up with test ideas immediately just by seeing an object modelled in a certain way. Settings that change behavior, size, complexity, force relationships to change, define what is and is not valid - lots of these sorts of ideas become more apparent when we model the objects and entities in our user stories.

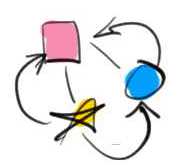

Model the relationships between objects

There is almost always some sort of relationship between use cases, scenarios, objects within the scenarios. Some things relate to each other as classifications. Some things relate to each other in time based sequences. Some things relate to each other as conditions affecting or causing other conditions.

Some types of objects, such as steps in a scenario, look like ordered linear relationships one at a time, but when modelled together create graphs with branches, loops, recursion, and other complexities. Often when we model such relationships we discover in the branches and conditions and loops, new steps and sequences and test conditions emerge that were not represented one at a time. Other possibilities suggest themselves. What if a relationship is broken, or violated? What if an implied step is skipped or a sequence aborted? What if an entire sequences is repeated, or interrupted with some new step?

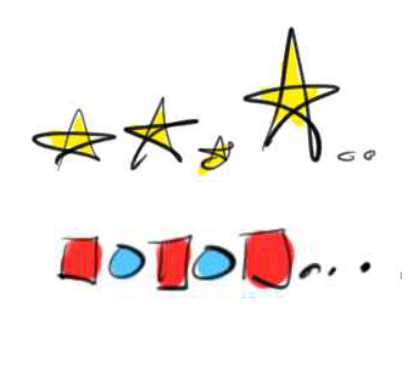

Do it over and over again

A lot of bugs can be found by doing something multiple times. We have a tendency to imagine our use cases as something which happens once and is done. There are a lot of bugs that show up if something is executed twice. Strangely, there are other seemingly arbitrary, random numbers of repetitions - such as being good at once, twice, and then for some unexpected reason you might have a bug at four. There are other classes of bugs that crop up doing something many times. A hundred, a thousand, ten thousand. Sometimes very difficult in some apps (especially in UI), but frequently an API is very easy to call a large number of times. This is often a good way to expose bugs not so much tied to exactly how many times something happens, but rather something that doesn’t happen often and repetition just increases the odds.

Change some attribute of the object

Once we have modelled something so that we understand its attributes, we can look at what happens when those attributes are changed. In our cartoon, the example circle was blue, so what about other colors? Are all colors equivalence class, or are some special? Maybe there is some other attibute, like size, perimeter border thickness, opacity, perimeter border color, perimeter border pattern, fill pattern?

Mix up sequences of items by type and attributes

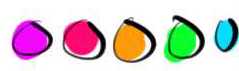

Another useful transformation is to mix things up. Different types of items, or same type of item but mixing the attributes. Sometimes an input set with a lot of variation along certain attributes creates problems when the inputs are more homogenous. Sometimes the nature of the mixture matters a lot. Maybe performance is optimized when the sequences are very random, and maybe performance degrades sharply when distribution is heavily skewed. Maybe inputs are assigned buffers of certain size, and certain combinations of input sequences throw off the buffer allocations.

Change the nature of the object in some way

The example input you were given is a circle. A circle is a very specific class of an oval. What about other oval shapes, and what about height versus width (or even rotational angle, not shown in the cartoon). What about circles that overlap each other? There are any number of transformations we can imagine of this sort.

Use examples other than what you were told as input

There is a popular joke that starts, “A tester walks into a bar…”, and somewhere in the joke is the statement, “…and orders an iguana.” Sometimes people look at examples of testing and laugh about what seems like a silly idea. Except that there are numerous instances where the tester tries something silly, and finds a serious bug doing it. In my cartoon, maybe I just wanted to draw a cow, but it serves as an example of trying an input that is radically different from the examples. Then again, maybe “cow” makes perfect sense as input to an image recognition system - it depends on what we are testing. To appease folks not so imaginative in their thinking, I also put a hexagon in the cartoon, hoping they would see how “another kind of basic geometric shape” might be closer to the examples while still looking for how the system handles something very different than given in the use case example.

Be more than a parrot and make something new

The main point I want anybody starting in testing to understand how important it is to immediately see beyond the requirements and user stories and scenarios that product managers and developers craft together. Those were made to guide the creation of the product, and generally a competent and responsible developer has already checked those requirements. When someone hands off such cases to a tester and the tester repeats exactly those cases, we are treating the tester like a very slow, someone hungry and tired robot. At some point, somebody is going to decide to save money on the expensive salary and ask the developer to handle those tests - and that developer is immediately going to automate it, because they don’t want to perform those steps themselves.

This kind of displacement is bad, but not because a tester is out of work. Working that way is inefficient and wise to optimize away. This kind of displacement is bad because very valuable and important testing was missing in the first place.

The tester should change them to make a different, much larger, much more complex, much more likely to discover and help you understand important bugs that represent risk to the customer, the product, and the business.