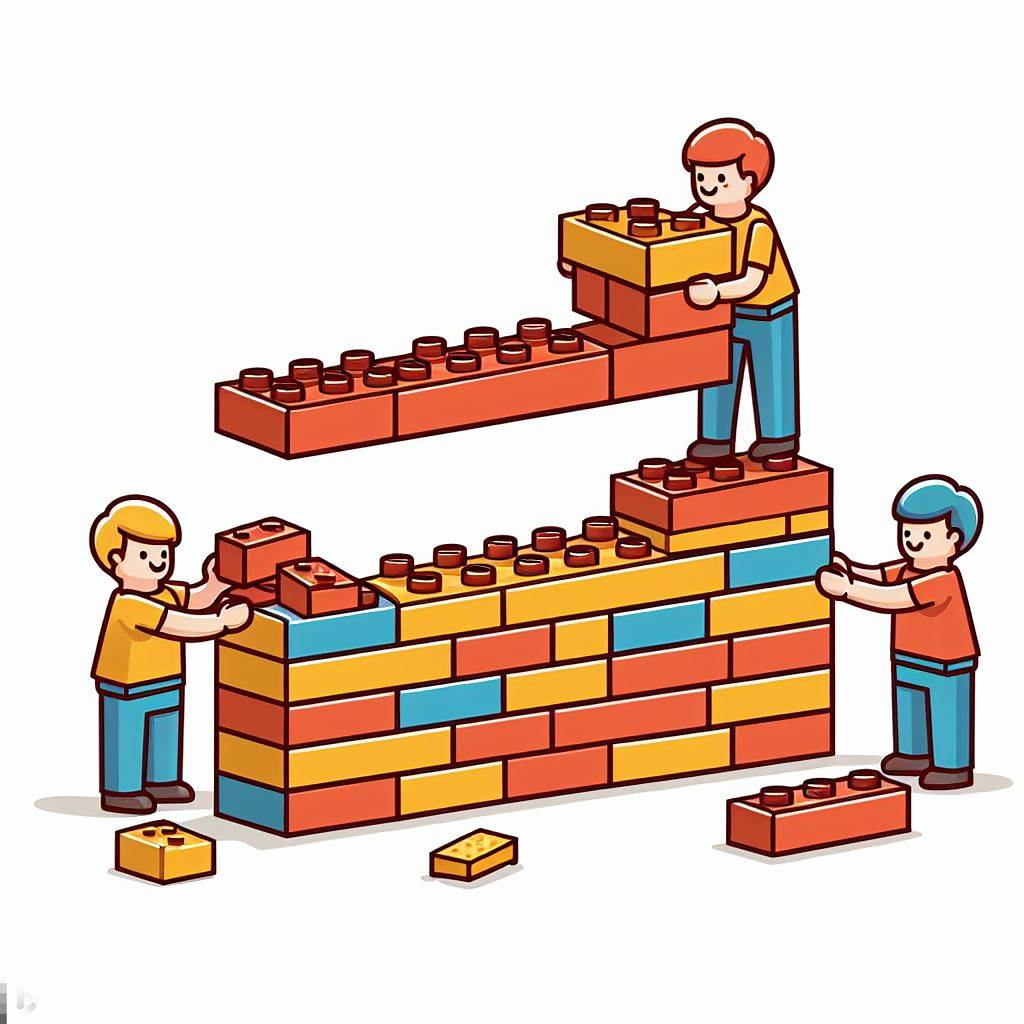

Think of testing across sprints like Lego bricks

I like this picture I am using because it has so many classic Lego mistakes in it,

which illustrates the point of the article. I especially love the free floating

row of bricks in the air, nothing tying them together. It also has

overlapping bricks, longer bricks connecting shorter bricks. I used Bing Image Creator for the

picture, and all the AI eccentricities help the story.

I like this picture I am using because it has so many classic Lego mistakes in it,

which illustrates the point of the article. I especially love the free floating

row of bricks in the air, nothing tying them together. It also has

overlapping bricks, longer bricks connecting shorter bricks. I used Bing Image Creator for the

picture, and all the AI eccentricities help the story.

Short bricks, long bricks, and overlapping bricks

Let’s talk about Legos first

If you have ever built a wall, or anything out of Lego bricks, you know that you cannot build any stable structure if the bricks all line up perfectly on their edges. If bricks are perfectly lined up on their edges, the structure will collapse. A stable wall requires bricks that overlap.

Sometimes we need short bricks. Windows in walls are a great “short brick” example. Sometimes we tie those short bricks together with longer bricks on the bottom and top. The short bricks fit the special shape we are trying to build, the longer bricks tie the structure together.

User stories are made of bricks

This is just a metaphor. It isn’t going to be perfect, so relax and enjoy the imagery.

A user story might be a single brick. A user story might be multiple bricks stuck together. A user story built of multiple bricks needs overlapping bricks, sometimes shorter and longer bricks, to make the story stable.

A code submission or a deployment can also be a brick. So can a sprint. It doesn’t matter so long as we recognize that joining multiple things together in a stable way, much like Lego bricks, requires longer and shorter bricks that overlap. Keep that picture in your head and you get the point.

Overlapping testing and deployment and user stories and sprints

Not all user stories and features fit in a sprint, never mind the deployments

Not all new product capabilities or user stories or features all fit in a single sprint. Frequently, we have some user story that builds on capabilities that came from other features or user stories or product changes. Inside sprints, especially if we are using a continuous integration, continuous deployment development model, the user story for that sprint is not going to all fit in one code submission or one deployment. The user story completes as the code in the different submissions tie together in progressive changes and submissions.

Testing doesn’t fit in the iteration anymore

Some projects treat testing like a gatekeeper event. Give the product code to a test team and ask them if the product meets the release criteria. That practice does not fit when code releases frequently (that practice was widely dismissed by many testing experts and test teams starting in the 1990s, but you still see it in practice even 30 years later). Many projects use a release model where once code is fully integrated with other code in the repository the product immediately deploys, relying on automatic processes to prevent the integration and monitor the deployment rather than asking a test team to approve the final deployment or release. Testing is supposed to happen before integration to the repository. Developers check their code, testers work with developers on earlier, shift-left collaboration to cover whatever work is happening in that sprint.

When the iteration is really fast (small bricks - imagine tiny, single post Lego bricks), with multiple code integrations a day, even the testing activity in the sprint cannot fit between every single code submission. The developer may be making changes that have enough coverage to have confidence they are safe to submit to the repository, but the feature work for that sprint is not necessarily complete. Meanwhile, there is testing, possibly from the developer, possibly from testers working with them, that span these multiple code submissions.

The same thing happens with user stories that require multiple sprints to come together. Some of these user stories are larger than one sprint of work, and some of their testing is larger than one sprint of work. Some of the testing, the parts that require full integration of many pieces, can build up progressively larger, but cannot complete until all the pieces are in place. Likewise, some of the development work for a larger, spanning sprint, cannot happen until all the other pieces are in place and may even be waiting on information from the testing activity to understand how to complete the work for that final sprint.

If you are imagining longer, overlapping Lego bricks snapping on top of shorter Lego bricks then you have the right picture in your head.

Bringing it all together

One argument out there suggests that our products can be built from releases of tiny little bricks. This is true.

Another argument out there suggests that tiny little bricks cannot sustain the needs of a product, and we need longer bricks to build a stable product. This is also true.

Both arguments are incomplete until you start tying them together. No structure is built out of independent, non-related parts. We build things out of different sized and shaped bricks that overlap with each other to bind them together.

Little kids learn this right away. Little kids know the structure comes from the bricks connecting with each other, overlapping with each

other. Little kids know they cannot build something stable out of singular bricks that line up perfectly, because they

know the brick is not the point. I have faith that adults in the software community can recall a lesson we learned when we were

much younger.

This image was generated by Bing Image Creator.

This image was generated by Bing Image Creator.