Automating The Hardest Testing Problem I Ever Had

A UI tightly coupled to everything is a testing and architectural nightmare

The prompt to Bing Image Creator for the above was “a tester frustrated trying to automate a web-UI that is too tightly coupled to its dependencies,”

and I believe that aside from the fact the guy is wearing a tie is

a brutally accurate depiction of me at the time of this story.

The prompt to Bing Image Creator for the above was “a tester frustrated trying to automate a web-UI that is too tightly coupled to its dependencies,”

and I believe that aside from the fact the guy is wearing a tie is

a brutally accurate depiction of me at the time of this story.

I got the idea for this story after a post from Bryan Finster that started off as follows:

I was talking to someone this morning about the challenges of UI testing. First, most people are taught to test the UI incorrectly. They default to coming in through the browser and doing a full E2E test instead of testing the behaviors in a more controlled way. It’s like trying to test a service through the API. Controlling state and test scope becomes a nightmare. The secret to a good test is the same as a good physics experiment; control your variables!

Bryan is referring to the type of testing you do in release pipelines. Later in comments on the post he says he fully supports exploratory testing, interactively, via the UI. The point that resonated with me is this point about control, and how test control is lost in the UI. Especially if you try to automate against it.

Sometimes that loss of control is an advanage. Sometimes it is very bad.

I have a story about it being very bad.

Testing SharePoint Online

I was working on the User Profile Service in Microsoft SharePoint Online. The service was less than a year old, and we were getting reports of data sync and data loss bugs. Some of the problems:

- Changes to user names, e.g. their last name, were not reflected on lists

- User property changes were not showing up in the user profile store

- Users were unable to get to their personal sites where their personal documents were stored

- Users were unable to get to their profile.

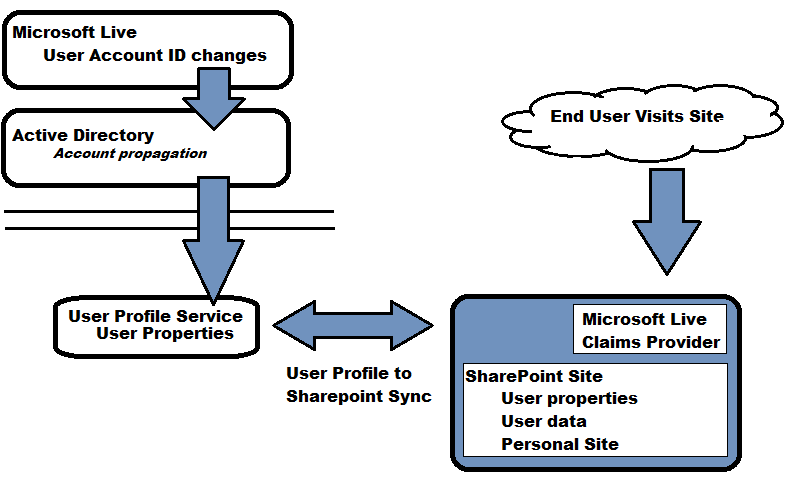

The entire problem came from a feature change in Microsoft Live that allowed users to change their ID (also called the User Principal Name). Microsoft Live was the backing identity service to all accounts on Office Online, of which SharePoint was a feature, but that group operated in a completely different department than Office and SharePoint. We did not know the feature was coming.

SharePoint had an arduous and difficult mechanism for changing user IDs

that in the on-premise product was something IT departments would manage

in batch during maintenance windows. The scenario did not have an equivalent

in SharePoint online. The result was that to SharePoint, the changed user ID

was an entirely new user when it came to looking up user data, but in terms

of authentication was the same user. This bug was brutally difficult to test

and investigate and fix, because it involved the interaction of multiple systems:

- Microsoft Live

- The Office 365 Active Directory servers

- User Profile Service sync with Active Directory

- List and user data storage in SharePoint Sites

- User personal sites in SharePoint, where the URI is based on the User ID

- The UI of SharePoint, which initiated its own local sync behavior when a user visited a site

- A synchronizatio process between the User Profile Service and the SharePoint site

The first two systems I could not affect or control. There was no programmatic access to any of them. Microsoft Live offered only UI interfaces for changing user IDs. Active Directory account propagation from changes in accounts happened on a schedule I could not control. Syncing of data from the AD to the User Profile Service also happened on a schedule I could not control. I needed to fake multiple layers to do any testing.

But another problem really made the testing difficult. Tightly coupled UI.

Testing a UI with tight coupling is a big problem

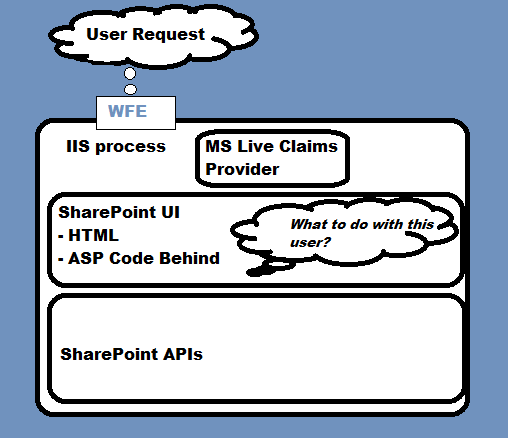

SharePoint handles multiple types of user authentication. Generally it uses claims based authentication to identify the user, so as long as a given authentication system has implemented a claims provider installed on the system, the user should be able to use SharePoint on whatever authentication system is available.

SharePoint Online used a Microsoft Live claims provider. Put a pin in that.

Inside SharePoint is logic that checks who the user is, and will do the following things:

- add them to a list of users for the site if they are new

- if they visit the personal site create one under the user ID if it is not created yet, otherwise direct to existing one

This logic is in the UI layer. SharePoint Online was written using Microsoft ASP, and behind the HTML is an executable binary referred to as “ASP Code-behind.” This executable creates the HTML and responds to front-end requests to either take some action on the service or to provide information the page can use to update its state.

The logic which determined who the user was, and whether or not the personal site was a new create or a redirect to existing page was in the ASP code-behind. The logic which determined if a user was new and needed to be added to the list of users on the site was in the ASP code behind. The ASP page called SharePoint APIs to act on all those decisions, but the decision itself was in UI code.

A good deal of the logic relied on calls to the HTTPContext object, something that is only available when the web-server is running and a visit to the page is invoked. This information was coupled with information retrieved from the user identity, the set of claims about the user. In particular, some of the code paths causing the bug would only happen if a user was coming from Microsoft Live. The UI code was checking for Microsoft Live account specific information.

This meant the following:

- test code could not use the SharePoint API

- test code had to perform all operations via the browser against a running Web UI

- the test code had to create a fake Microsoft Live claims provider

Some testing context

This was sometime between 2010 and 2012. Testing was a separate discipline from Development at Microsoft at the time. I was an individual contributor SDET.

Testers did not touch product code. Testability was an ask, a request, a negotiation. What really should have happened is somebody should have seen how tangled up the UI in SharePoint was to core business logic and created a clean separation to get the business logic pushed into the API. That wasn’t going to happen. That sort of thing didn’t start happening until after 2014 when all the testers and developers were turned into Software Engineers and everybody had to do their own testing.

But that is another story. The main point, I was stuck having to write the automation to this problem with a full stack that I was not allowed to change.

Automation, you say? Why not just…?

There were multiple events I had to synchronize in strict ordered control:

- User Principal Name change of a given account

- Syncrhonization of user accounts from the identity service (AD - which I had to mock) to User Profile Service

- Synchronization of User Profile Service account data to the SharePoint site

- An end user visiting a SharePoint site

- An end user creating data in a SharePoint list

- An end user visiting the SharePoint personal site

Those operations, in different order and sequences, multiple times each, defined the test problem domain. The state machine was massive. I had determined a set of 7 different failure modes that reduced the matrix, but there was still other non-broken traversals of the state that needed to happen. That timing and volume was only feasible if I automated the behaviors. “Manual testing” was a no-starter.

What I did

- Backward engineered the Microsoft Live claims provider and wrote my own. This took two weeks of reading the SharePoint code to determine what it believed a Microsoft Live claims provider looked like, because there was no documentation.

- Create an in-memory user identity service that the claims provider would use to get accounts from and which I could forcibly sync to the User Profile Service on-demand. I added an API to this service that allowed me to change the User Principal Name of a user at will

- Created test library tasks to invoke User Profile to SharePoint sync, and to have the user visit each of the relevant SharePoint UI locations to cover the tests

This done, I was able to run the entire scenario on a single box, Microsoft Live and Active Directory completely removed from the environment. I still had to have the SharePoint site up and running inside IIS and come in through the UI.

This was a tremendous amount of work, but we were losing a lot of money from angry customers online dropping subscriptions. We needed something to cover changes on this set of features as we fixed the bugs.

Two issues here about tightly coupled UI made the above automation far more difficult:

- Tight coupling to Microsoft Live: I could have used simpler identity models than having to mock the Microsoft Live claims provider if the logic was not so tightly tied to Microsoft Live specifics

- Business logic in the UI layer instead of SharePoint API: UI automation is fragile and slow and introduces so many more issues into the stack. If the business logic had been moved lower the testing could have happened at the API. Were logic decoupled even more, the conditions could be tested as a matter of contracts rather than the system running end to end.

The lesson learned

My takeaway is that I personally felt the pain over the span of a couple of months that came from tightly coupled UI, business logic, and dependencies which cost the company a lot of money and made a problem far more difficult to test than it should have been. The post from Bryan Finster mentioned at the top of the article brought back these memories.

An important part of good testing is setting up the tester to succeed. The more you couple code together, the harder the problem the tester is going to have. It doesn’t matter who your tester is - a dedicated testing professional, the developer on the code, a member of the product management team, anybody else from the team - they life will be so much easier, and your product so much better, if you choose designs that are easier to test.